Important attention has been drawn to the shameful condition of middle income housing affordability in California. The state that had earlier earned its own "California Dream" label now limits the dream of homeownership principally to people either fortunate enough to have purchased their homes years ago and to the more affluent. Many middle income residents may have to face the choice of renting permanently or moving away.

However, finally, an important organ of the state has now called attention to the housing affordability problem. The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) has published "California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences," which provides a compelling overview of how California’s housing costs have risen to be by far the most unaffordable in the nation. It also sets out the serious consequences.

The LAO says that:

Today, an average California home costs $440,000, about two-and-a-half times the average national home price ($180,000). Also, California’s average monthly rent is about $1,240, 50 percent higher than the rest of the country ($840 per month).

LAO describes the evolution:

Beginning in about 1970, however, the gap between California’s home prices and those in the rest country started to widen. Between 1970 and 1980, California home prices went from 30 percent above U.S. levels to more than 80 percent higher. This trend has continued.

Much of the LAO focus is on California’s coastal counties, where:

….community resistance to housing, environmental policies, lack of fiscal incentives for local governments to approve housing, and limited land constrains new housing construction.

These causes result from conscious political decisions. While California’s coastal counties do not have the vast stretches of flat, appropriately developable land that existed 50 years ago, building is increasingly prohibited on that which remains (for example, Ventura County, northern Los Angeles county and the southern San Jose metropolitan area).

Demonstrating an understanding of economic basics not generally shared by California policymakers or the urban planning community, LAO squarely places the blame on the public policy limits to new housing construction:

This competition bids up home prices and rents.

In other words, where the supply of a demanded good is limited, prices can be expected to rise, other things being equal. LAO describes the impact of so-called "growth control" policies, which are also called "urban containment" or "smart growth:"

Many Coastal Communities Have Growth Controls. Over two-thirds of cities and counties in California’s coastal metros have adopted policies (known as growth controls) explicitly aimed at limiting housing growth. Many policies directly limit growth—for example, by capping the number of new homes that may be built in a given year or limiting building heights and densities. Other policies indirectly limit growth—for example, by requiring a supermajority of local boards to approve housing projects. Research has found that these policies have been effective at limiting growth and consequently increasing housing costs.

According to LAO, the problem is exacerbated by voter initiatives: "More often than not, voters in California’s coastal communities vote to limit housing development when given the option." It is hard to imagine a more sinister disincentive to aspiration, under which voters can deny equality of opportunity in housing to others by artificially driving up the price. Because new housing further from coast is also limited, options for a middle income living standard are also diminished.

These public policies have consequences.

Notable and widespread trade-offs include (1) spending a greater share of their income on housing, (2) postponing or foregoing homeownership, (3) living in more crowded housing, (4) commuting further to work each day, and (5) in some cases, choosing to work and live elsewhere

Each of these consequences is described below.

LAO Consequence #1: Spending a Greater Share of Income on Housing

LAO models the market situation from 1980 to 2010 to estimate the prices that would have prevailed if the regulatory environment had permitted building sufficient to satisfy customer demand at previous lower price levels. In both years, LAO estimates that the median priced house would have cost 80% more than in the rest of the nation (actual data in 1980, modeled data in 2010). This would have kept California house price increases at the national level. I think it would have been better to have modeled from 1970, before the huge house prices before 1980 described by Dartmouth economist William Fischel.

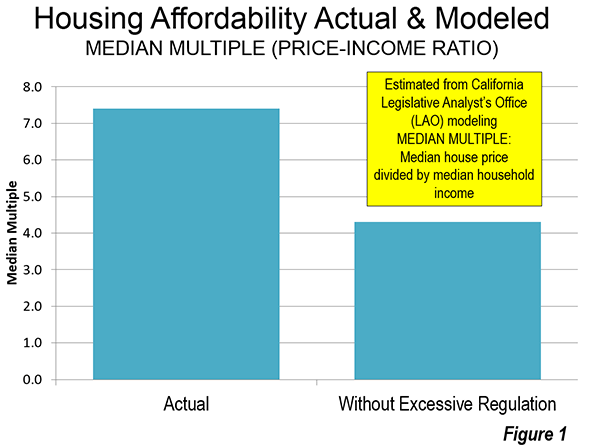

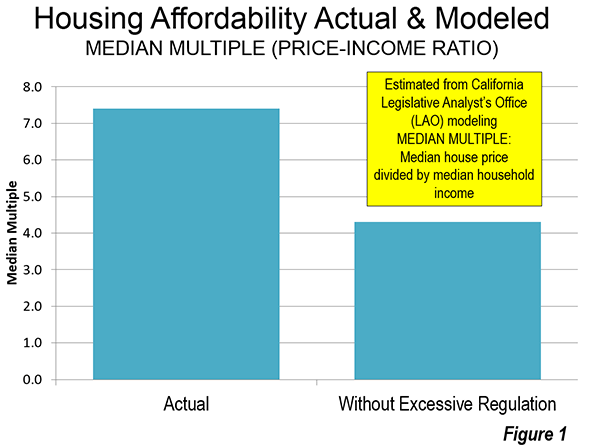

I have applied this LAO model estimate to the median multiple for California’s six major metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, San Francisco-Oakland, Riverside-San Bernardino, San Diego, Sacramento, and San Jose) to identify how much better middle income housing affordability would be without California’s excessive regulation. Using the LAO estimates the median multiple (median house price divided by median household income) in 2014 would have been at least 40% lower than the actual level in each of the metropolitan areas (Figure 1).

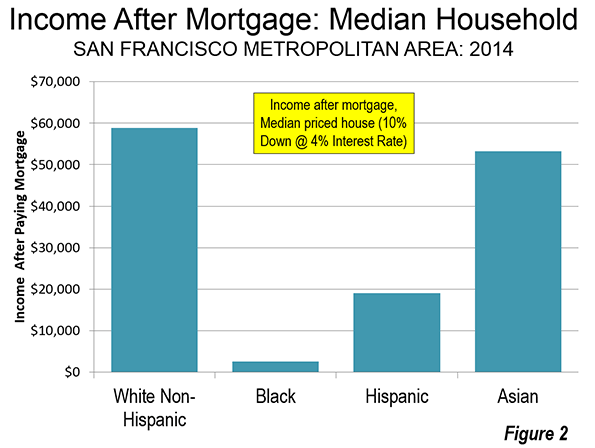

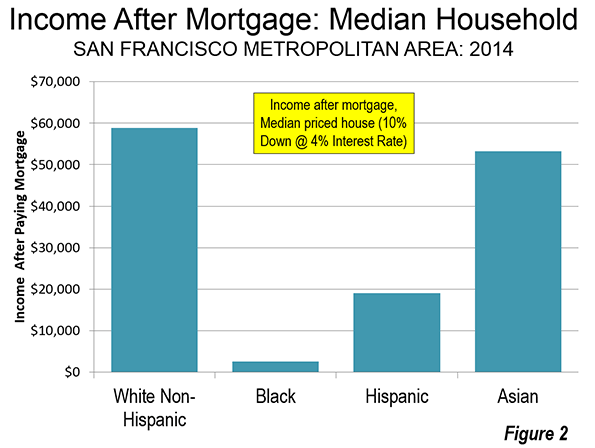

Many California households already have been priced out of the market. In the worst case, it is estimated that in the San Francisco metropolitan area, a median income White Non-Hispanic household will have nearly $60,000 annually left over after paying the mortgage on the median priced house. This is less than they would have if house prices had remained reasonable, but it’s enough to live on. The median income Asian household would do almost as well, with about $50,000 left over. The median income Hispanic household would have less than $20,000 left, which is considerably less than is likely to be needed for other essentials. The median income Black household would have less than $3,000 left over (Figure 2). If the price ratios of 1980 were controlling, that amount would rise by $16,000.

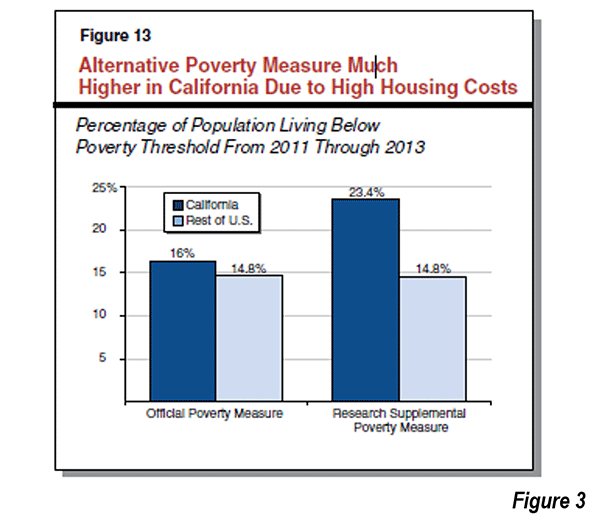

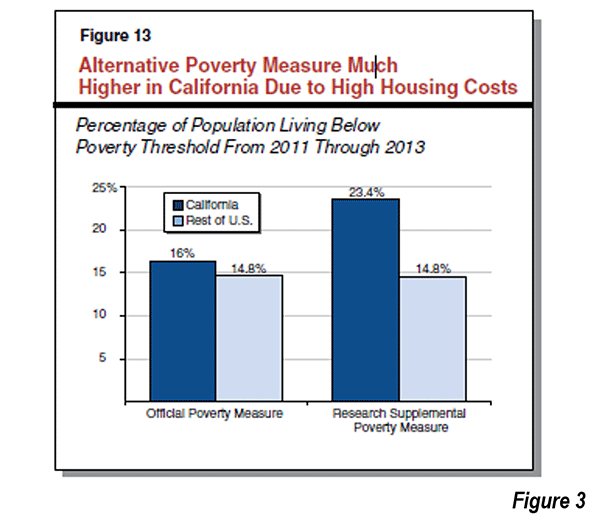

LAO also points out that the Golden State has the highest housing cost adjusted poverty rate in the nation. The latest data shows housing-adjusted poverty rate is far higher even than that in states with a reputation for grinding poverty. California’s housing adjusted poverty rate is more than 50% higher than that of Mississippi and approaches double that of West Virginia (Figure 3, LAO Figure 13)

LAO Consequence #2: Postponing or Forgoing Homeownership

LAO indicates that California ranks 48th in homeownership percentage, behind only New York and Nevada. LAO emphasizes the value of home ownership:

Homeownership helps households build wealth, requiring them to amass assets over time. Among homeowners, saving is automatic: every month, part of the mortgage payment reduces the total amount owed and thus becomes the homeowner’s equity. For renters, savings requires voluntarily foregoing near-term spending. Due to this and other economic factors, renter median net worth totaled $5,400 in 2013, a small fraction of the $195,400 median homeowner’s net worth.

Californians are buying their first houses later. LAO indicates that the average first home buyer in California is three years older than the national average.

LAO Consequence #3: Living in More Crowded Housing

The nation’s worst overcrowding is an unfortunate result of California’s housing policies.

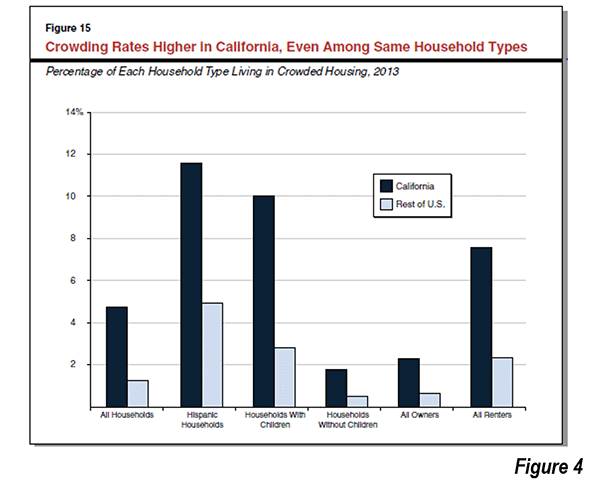

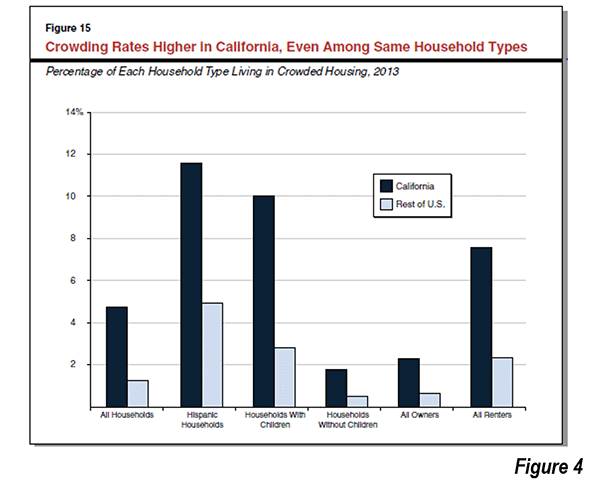

LAO indicates that California’s overcrowding rate is well above that of the rest of the nation’s rate. Among Hispanics, which were expected to exceed the White-Non-Hispanic population in 2014, to become the state’s largest ethnic group, California overcrowding is more than 2.5 times the Hispanic rate elsewhere. Among households with children, overcrowding in California is four times the national households with children rate. Among renters, overcrowding in California is more than three times the national renter rate (Figure 4, LAO Figure 15).

This has important negative social consequences. According to LAO, research indicates that overcrowding retards well-being and educational achievement:

Individuals who live in crowded housing generally have worse educational and behavioral health outcomes than people that do not live in crowded housing. Among adults, crowding has been shown to increase stress and aggression, lead to social isolation, and weaken relationships between parents and their children. Crowding also has particularly notable effects on children. Researchers have found that children in crowded housing score lower on standardized math and reading exams. A lack of available and distraction-free studying space appears to affect educational achievement. Crowding may also result in sleep interruptions that affect mood and behavior. As a result, children in crowded housing also displayed more behavioral problems at school.

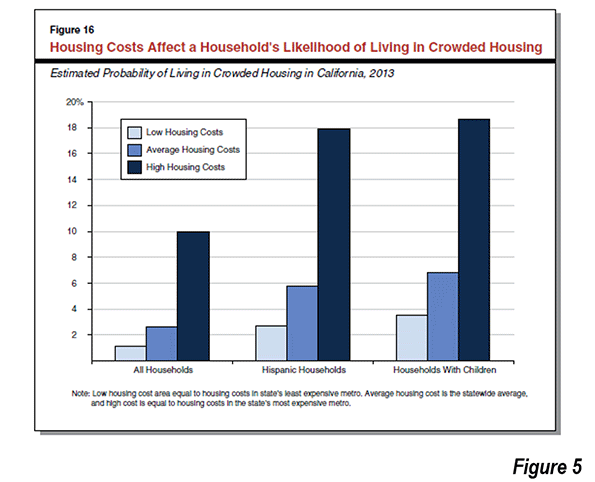

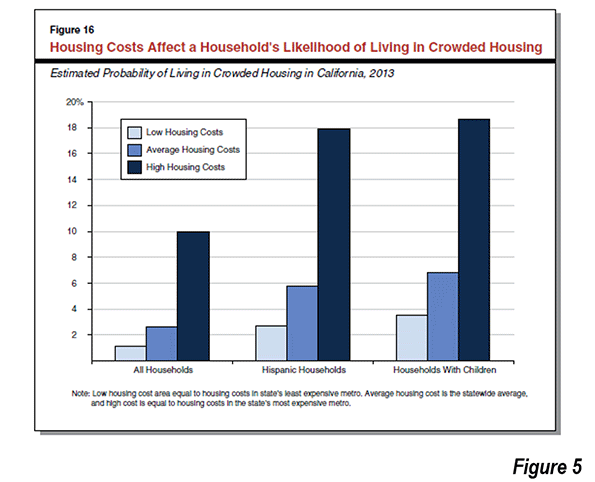

Overcrowding is particularly acute in the higher cost coastal metropolitan areas of Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, and San Jose. There, overcrowding among households with children reaches 10%, and among Hispanic households, overcrowding reaches 18%. Among households with children the figure is slightly higher (Figure 5, LAO Figure 16). Overcrowded housing is generally worse, according to LAO, in areas with higher house prices.

In a state with a political establishment that prides itself in watching out for low income citizens and ethnic minorities, the need to reform the responsible policies could not be clearer.

LAO Consequence #4: Commuting Farther to Work

LAO finds that California’s average work trip commuting times are only moderately above the national average. However, LAO suggests that the commute lengthening impact of higher house prices may be reduced by California’s widespread (I call it dispersed) development pattern, its freeway system and the "above-average share of commuters who drive to work. (Driving commutes are generally fast, and therefore metros with higher shares of driving commuters tend to have shorter commute times.)"

Nonetheless, according to LAO:

…our analysis suggests that California’s high housing costs cause workers to live further from where they work, likely because reasonably priced housing options are unavailable in locations nearer to where they work.

LAO Consequence #5: Choosing to Work and Live Elsewhere

LAO also indicates that California’s high housing prices are likely to have reduced its population (and economic) growth. LAO sites the strong net outmigration of California households to other states. LAO also finds in its national metropolitan area analysis that counties with higher growth rates tend to have better housing affordability than counties with lower growth rates.

There has also been strong net outmigration from the coastal counties to inland counties. This is most evident in the growth of the Riverside-San Bernardino metropolitan area (the Inland Empire) between 2000 and 2010. The Inland Empire captured more than two thirds of the population growth of the Los Angeles Combined Statistical Area (Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties). LAO notes the impact of the excess of demand in the coastal counties, again recognizing the nexus between overzealous regulation and the loss of housing affordability:

This competition bids up home prices and rents. Some people who find California’s coast unaffordable turn instead to California’s inland communities, causing prices there to rise as well.

LAO also refers to the difficulty that employers have in retaining and recruiting staff. LAO cited survey data from the Silicon Valley, which has for years been California’s economic "Golden Goose" in recent years:

In a 2014 survey of more than 200 business executives conducted by the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, 72 percent of them cited “housing costs for employees” as the most important challenge facing Silicon Valley businesses.

In addition, there has been a strong movement of California companies to other parts of the nation, where more liberal regulations foster a better business climate.

Restoring Housing Affordability

LAO indicates the importance of fundamental reform and calls for putting "all policy options on the table."

Major changes to local government land use authority, local finance, CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act), and other major polices would be necessary to address California’s high housing costs.

In addition:

The greatest need for additional housing is in California’s coastal urban areas. We therefore recommend the Legislature focus on what changes are necessary to promote additional housing construction in these areas.

Perhaps the only weakness of the report deals with densification, particularly in coastal counties. For example, LAO suggests that without the housing restrictions the city of San Francisco is population would be 1.7 million, rather than the approximately 800,000 who live there today. In fact that would be unprecedented beyond belief. No core city that had become fully developed and reached 500,000 people by 1950 has achieved growth of this magnitude. The greatest growth was less than 10%, in this category of 60 core cities (which includes the city of San Francisco). Even less likely would be public support for such huge population growth in the second densest major municipality in the nation.

While LAO does not indicate the additional population that its estimates would have placed in the core of Los Angeles, given the scale of the San Francisco increase, this could be a number of up to 3 million. This area, the broadest expanse of over 10,000 population per square mile density in the nation outside New York City is in the middle of the urban area with the nation’s worst traffic congestion, according to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. It is doubtful that residents would have the "stomach" to expand roadway capacity to keep the traffic moving. Transit could not have made much difference. Even with its now extensive rail network that has opened since the early 1990s, driving alone accounted for 85% of the additional travel to work from 2000 to 2013 in the city of Los Angeles. Yet, the city of Los Angeles has the most extensive transit in the metropolitan area, including service by all rail lines.

In reality, core densification is likely to be modest. Keeping housing affordability from getting worse requires regulatory liberalization throughout California, including coastal and inland areas

The reality is that if California had permitted growth, it would naturally occurred mostly on the periphery. Even with the restrictions on building, the preference for suburban living (largely in detached housing) could not be repressed between 2000 and 2010. Less than 10% of the population growth in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas occurred in the cores.

The Challenge

Should the state of California begin to seriously discuss housing affordability, it will be important to ease restrictions throughout the state, not just in the coastal counties. There are serious barriers to placing the appropriate priority on improving the standard of living and minimizing poverty rates among California’s diverse population. Perhaps the biggest impediment is Senate Bill 375, which is being interpreted by the state and its regional planning agencies to require even more stringent land-use regulation.

In this environment, LAO rightly raises this concern:

If California continues on its current path, the state’s housing costs will remain high and likely will continue to grow faster than the nation’s. This, in turn, will place substantial burdens on Californians—requiring them to spend more on housing, take on more debt, commute further to work, and live in crowded conditions. Growing housing costs also will place a drag on the state’s economy.

It is to be hoped that California’s distorted policy priorities will be righted to restore the California Dream.

Photograph: Dense suburban development: Inland Empire (San Bernardino Freeway with Uplard toward the top and Ontario toward the bottom) – By author

Wendell Cox is an international public policy consultant and principal of Demographia in St. Louis. He is a native Los Angelino, having been born within two miles of City Hall. He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. Full biography is here.

David S. Holloway/Getty

David S. Holloway/Getty