A ground-breaking study of intergenerational income mobility has the enemies of suburbia falling all over themselves to distort the findings. The study, The Spatial Impacts of Tax Expenditures: Evidence from Spatial Variation Across the U.S. (by economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren of Harvard University and Patrick Kline and Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley). Chetty, et al. examined income mobility by comparing the income quintiles (20 percent) of households with children (between 1996 and 2000) compared to their own household income quintiles as adults in 2010/1. The children were all born in 1980 or 1981. The authors summarize their research as follows:

“We measure intergenerational mobility at the local (census commuting zone) level based on the correlation between parents’ and children’s earnings. We show that the level of local tax expenditures (as a percentage of AGI) is positively correlated with intergenerational mobility.”

The Over-Reach

One of their findings was that children born in the Atlanta area had less upward income mobility than in most other metropolitan areas (Note 1). This provided all that was needed for a spin by others that distorted the findings into a completely different story than supported by the data.

New York Times reporter David Leonhart started it, sprucing up the conclusions to produce anti-sprawl tome. He accomplishes this by unearthing anecdotes about the difficulty low income workers face getting to work in Atlanta, and blaming that urban area’s lower density suburbanization. However, the same anecdotes could have been woven from every metropolitan area in the nation (Note 2), regardless of their extent of suburbanization. More importantly, the research is not about sprawl.

Nonetheless, Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman then piled on, writing in The New York Times that Leonhart’s article had shown “how sprawl seems to hurt social mobility.” Krugman continued the next day with his “sprawl-caused-Detroit’s bankruptcy” thesis, which relied on an apples-to-oranges comparison (See: Detroit Bankruptcy: Missing the Point). Then on July 28, Krugman wrote: “…in one important respect booming Atlanta looks just like Detroit gone bust: both are places where the American dream seems to be dying” (Note 3). Krugman calls Atlanta the “Sultan of Sprawl.”

Professor Steven Conn of Ohio State University took it a bit further in the Huffington Post, saying that: “One of their findings is that mobility is more restricted in places defined by suburban sprawl — like Atlanta and Columbus, Ohio — than in denser, more urban places like San Francisco and Boston. Far from being good for the nation, our love affair with the car, and the sprawl it has produced, keeps people from moving up the economic ladder.”

The Research

The authors of the report reached their conclusions using regression analyses and controlling for demographic factors, with the objective of identifying associations between upward income mobility and tax expenditures, not suburbanization. In fact, the very issue of transportation and density was simply not a factor.

The authors provided additional information with 25 separate, simple correlation analyses between 25 individual variables and economic mobility (demographic factors were not controlled). Co-Author Raj Chetty described this supplemental research in a PBS interview, citing income segregation, school quality, two-parent families and measures, civic engagement, religiosity and community cohesiveness. The authors urged caution in interpreting these correlations: “For instance, areas with high rates of segregation may also have other differences that could be the root cause driving the differences in children’s outcomes.”

Rational Responses

The overreach was challenged by Columbia University urban planning professor David King, who pointed out that the best ranked cities in the upward mobility analysis were all “sprawling,” including Salt Lake City, Santa Barbara and Bakersfield, which he referred to as a “poster child for sprawl.” He further noted that: “…snapshot correlations really don’t mean anything and will provide evidence for whatever point of view is desired.”

Randal O’Toole of the Cato Institute similarly questions the unfounded interpretations of the study and notes that Atlanta has invested billions in new transit systems over recent decades, but with no appreciable impact on how the poorest citizens did there.

University of Southern California economics professor Peter Gordon suggested that: “In the fast-and-loose manner that some have digested the Chetty et al. study, we could conclude that sprawl causes upward mobility.”

Pinnacles of Prosperity

Interestingly, if, as Krugman alleges, Atlanta is the Sultan of Sprawl, then similarly sprawling Hartford is the “Pinnacle of Prosperity.” Hartford has the highest per capita gross domestic product of any metropolitan area in the world. Yet, the urban area density of Hartford is 1,791 per square mile (692 per square kilometer), little above Atlanta (1,707 and 659), but two-thirds less than less affluent New York (5,319 and 2,054) and three-quarters less than less affluent Los Angeles (6,999 and 2,702), according to the 2010 census (Note 4).

The reality is that the US has the world’s most sprawling cities, yet the 50 most affluent metropolitan areas per capita in the world include 38 in the United States. This includes the top eight, such as lower density Bridgeport (urban density 1,660 per square mile/641 per square kilometer), Boston (2,232/862) and Durham (1,913/739), as well as metropolitan areas with higher urban densities, San Francisco (6,266/2,419) and San Jose (5,820/2,247). Neither high-density New York nor Los Angeles makes the top 10. America’s greater dispersal is associated with the shortest commute times in the high income world, the least intense traffic congestion and some of the most affordable housing, if metropolitan areas subject to urban containment (smart growth) policies are excluded.

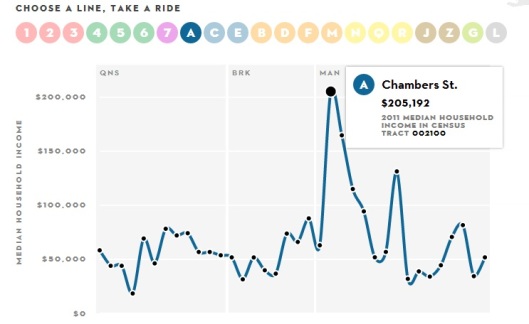

Moreover, the Chetty, et al data gives little comfort to any whose conception of good and evil depends on sprawl. The research aggregates upward mobility data for all counties within each commuting zone. Among major metropolitan areas, that includes counties from the most dense (New York County at 71,000 per square mile or 27,000 per square kilometer) to Skamania County in the Portland area, with a density of 7 per square mile or 3 per square kilometer. County level analysis could make a difference.

This is illustrated by the New York metropolitan area, which Chetty, et al divide into multiple commuting zones. The Tom’s River commuting zone, made up of outer suburban Monmouth and Ocean counties in New Jersey showed better upward income mobility (10.4 percent) than the New York commuting zone (9.7 percent) which included the city of New York, Nassau, Suffolk and Westchester counties. It might be interesting, for example, to compare the data, say for highly urban The Bronx to suburban Suffolk County, but the data does not permit that. This is not to criticize the Chetty, et al work; it is rather to suggest caution in inventing conclusions.

Smaller May be Better

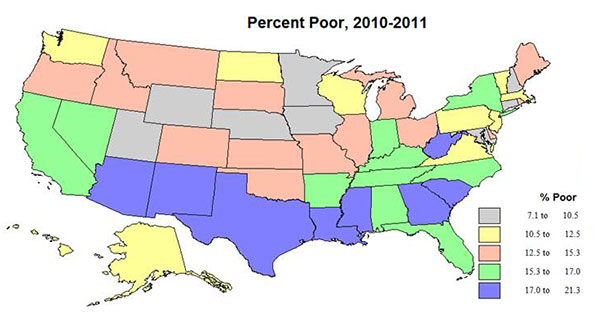

Further, commuting zones with smaller populations have generally better upward income mobility. Rather than an ode to bigness, the study found that commuting zones with less than 100,000 population average have higher than average upward income mobility. Virtually all of the smaller areas are low density and have little or no transit. Indeed, the best performers were in the Great Plains, in a swath from West Texas, through Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and reaching a zenith in South Dakota and North Dakota, which is about as far from dense urbanization as it is possible to get. Further, a large majority of the highest scoring commuting zones with larger populations, like Bakersfield and Des Moines, are highly dispersed (Table below). This could be an area for further research.

| Geographical Income Mobility |

| Population of Commuting Zone |

Upward Mobility |

Cases |

| Over 1,000,000 |

7.5% |

62 |

| 500,000 to 1,000,000 |

7.6% |

60 |

| 250,000 – 500,000 |

8.6% |

89 |

| 100,000-250,000 |

9.0% |

167 |

| 50,000-100,000 |

10.4% |

129 |

| 25,000-50,000 |

13.0% |

88 |

| Under 25,000 |

13.9% |

146 |

| Average/Total |

9.5% |

741 |

|

|

|

| Upward mobility: 30/31 year olds reaching top income quintile by 2010/1, from households in the bottom quintile in 1996-2000 |

| Commuting zones are similar to metropolitan areas |

Additional Caveats

There is no question but that this is ground-breaking research. The authors deserve considerable credit for the unprecedented scale of their analysis, which included over 6.2 million observations. However, the available data had an important limitation. The IRS data set they used does not go back far enough to make similarly robust findings about peak adult earnings. Age 30 or 31 may premature for predicting longer run income mobility. At that age, many who will eventually earn much more are not far into their careers. This would include people who have spent longer in higher education, such as those who have earned professional degrees. Finally, the median income of households in the 30 to 31 age category is barely 1/2 of their parents in the same, which, again, is not likely to be representative of their eventual income and quintile ranking over their adult lives.

The findings would be appropriately characterized as relating to young adult income upward mobility. Conclusions about lifetime upward mobility or peak earnings upward mobility will need to wait a decade or more.

The Second Half of the Story: Where People Moved

The authors use the childhood residence in the study, both for the child and the adult. This means, for example, that if a child lived in the New York metropolitan area and moved to Atlanta by 2010 or 2011, he or she would be counted in the New York data. Where people lived as children is the first half of the story. The second half is where they moved.

This is important, because so many people moved away from places like New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, and San Jose during the period the study covers. Approximately 10 percent of the residents of New York and Los Angeles moved elsewhere between 2000 and 2010. Approximately 8 percent left San Francisco, 13 percent left San Jose and 5 percent left Boston. These are not small numbers and indicate that more people left than moved in. A net 1.9 million left New York, 1.3 million left Los Angeles, 340,000 left San Francisco, while 230,000 left San Jose and Boston.

Some of the metropolitan areas that have gained the most domestic migrants scored below average on upward income mobility. For example, migration from other parts of the nation added 24 percent to Raleigh’s population in the 2000s, 17 percent to Charlotte, 11 percent to Tampa-St. Petersburg, and 10 percent to Atlanta (Note 5).

None of this contradicts the Chetty, et al findings, which did not address the question of why some many people have moved. It can be assumed that people who are doing well economically will probably stay where they are. On the other hand, most who leave might be thought of as seeking better opportunities that might elude them in the richer, slower growing, far more expensive metropolitan areas of their childhood. The idea that people left New York, Boston or Los Angeles for a less rewarding life in Atlanta, Charlotte, or Raleigh violates everything we know about human nature.

Seeking Prosperity

Throughout history, and especially over the last 200 years, cities have drawn people from elsewhere by facilitating opportunity. It is no different today. People move to satisfy their aspirations. This was the point of our recent "Aspirational Cities" report in The Daily Beast.

Chetty et al conclude: “What is clear from this research is that there is substantial variation in the United States in the prospects for escaping poverty.” True. It is also clear from actual behavior that, for many, the best prospect for escaping poverty may be the better opportunities that attract them to an aspirational city.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

—-

Note 1: Chetty, et al use “commuting zone” as their unit of geographical analysis. These areas are generally similar to metropolitan areas, but there are some important differences. For example, the New York metropolitan area is divided into three parts (New York Newark and Tom’s River). The Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area is divided into two. Los Angeles, Riverside-San Bernardino and Oxnard are combined as are Rochester and Buffalo. All of Connecticut, which has four metropolitan areas, is a single commuting zone. Areas outside metropolitan areas are also divided into commuting zones.

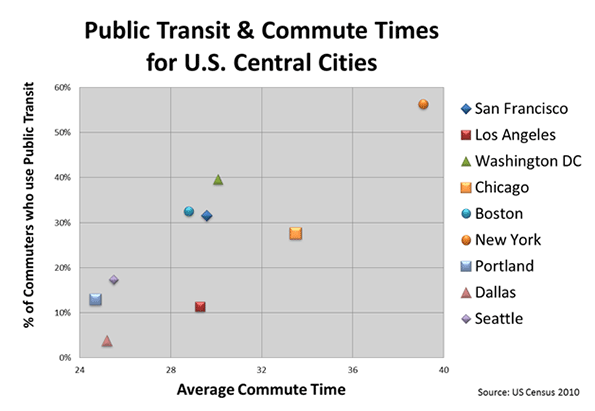

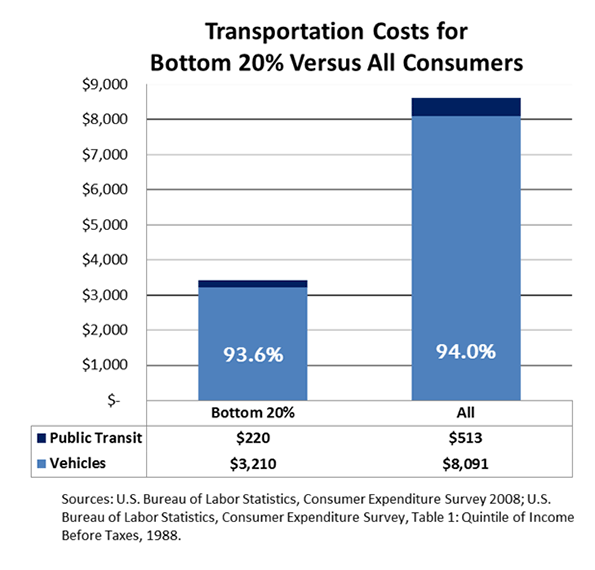

Note 2: The overwhelming share of low income workers drive to work (see How Lower Income Citizens Commute). Even, in metropolitan Boston, with its better than average transit system, few of the city’s low income residents can reach suburban job locations in less than one hour (the average commute time for all residents is less than one-half that). Despite popular impressions to the contrary, most jobs cannot be reached in a reasonable period of time by transit in any metropolitan area, nor is there any practical (affordable) way to change that.

Note 3: To the contrary, the American Dream is alive and well in Atlanta. Atlanta’s housing affordability is unrivaled by nearly all major metropolitan areas. Housing is four times as expensive relative to incomes in San Francisco and San Jose as in Atlanta (measured by the “median multiple”) three times as high in New York and Los Angeles and twice as costly in Portland. This makes housing more affordable for low income households. Not surprisingly, Atlanta households with less than $20,000 in annual income (approximately the lowest quintile) have a higher home ownership rate than in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Boston and Portland. Further, the gap with respect to African-American home-ownership is substantial. Atlanta’s African-American home ownership rate is approximately 40 percent above those of San Jose and Los Angeles, approximately 50 percent higher than Boston, San Francisco and Portland and nearly 60 percent higher than New York (American Community Survey, 2011).

Note 4: These are US Bureau of the Census urban area density figures, based upon continuous urban areas (“built-up” areas). Urban area densities are calculated using census blocks, and contain no rural land. As a result, their population densities are not distorted by jurisdictional borders. This is to be distinguished from any metropolitan area based measure. All metropolitan areas include urban areas as well as rural areas that are economically connected to the urban area. The extent of rural areas within a metropolitan area is driven by the geographical size of counties and thus varies widely. The largest major metropolitan area county, San Bernardino (California) is nearly 1,000 times as large as the smallest, New York County. If metropolitan area criteria were applied at the census block level, as is the case in urban areas, large swaths rural swaths would be removed from metropolitan areas, changing the density distribution. However, even if metropolitan areas were more appropriately defined, any measure of metropolitan density would remain a mixed urban-rural metric, not a measure of urban density. Here are the 2010 criteria for defining urban areas and metropolitan areas.

Note 5: There is less black-white racial segregation in Atlanta than in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, and most other major metropolitan areas, according to 2010 data compiled by William Frey of the Brookings Institution.