A good friend of mine, a Democratic mayor here in California, describes the Obama administration as “Moveon.org run by the Chicago machine.” This combination may have been good enough to beat John McCain in 2008, but it is proving a damned poor way to run a country or build a strong, effective political majority. And while the president’s charismatic talent – and the lack of such among his opposition – may keep him in office, it will be largely as a kind of permanent lame duck unable to make any of the transformative changes he promised as a candidate.

If Obama wants to succeed as president he must grow into something more than movement icon, become more of a national leader. In effect, he needs to hit the reset button. Here are five key changes that Obama can implement to re-energize and save his presidency.

1. Forget the “Chicago way.” The Windy City is a one-party town with a shrinking middle class and a fully co-opted business elite. The focused democratic centralism of the machine – as the University of Illinois’ Richard Simpson has noted – worked brilliantly in the primaries and even the general election campaign. But it is hardly suited to running a nation that is more culturally and politically diverse.

The key rule of Chicago politics is delivering the spoils to supporters, and Obama’s stimulus program essentially fills this prescription. The stimulus’s biggest winners are such core backers as public employees, universities and rent-seeking businesses who leverage their access to government largesse, mostly by investing in nominally “green” industries. Roughly half the jobs saved form the ranks of teachers, a highly organized core constituency for the president and a mainstay of the political machine that supports the Democratic Party.

The other winners: big investment banks and private investment funds. People forget that Obama, even running against a sitting New York senator, emerged as an early favorite among the hedge fund grandees. As The New York Times’ Andrew Sorkin put it back in April, “Mr. Obama might be struggling with the blue-collar vote in Pennsylvania, but he has nailed the hedge fund vote.”

At best, the president’s policy seems like Karl Rove in reverse, essentially smooching the core and ignoring the rest. This is a formula for more divisiveness, not the advertised “hope” Americans expected last November.

2. Focus on Real Jobs, Not Favored Constituencies . The Chicago approach works better in a closed political system controlled by a few powerbrokers than in a massive continental economy like the U.S. Health care and education, which depend on government largesse, are surviving. But the critical production side of the economy that generates good blue-collar jobs – like agriculture, manufacturing and construction – is getting the least from the stimulus.

These industries need more large-scale infrastructure spending, as well as more focused skills training and initiatives to free capital for politically unconnected entrepreneurial businesses. Instead, productive industries face the prospect of more regulation while capital for small businesses continues to dry up.

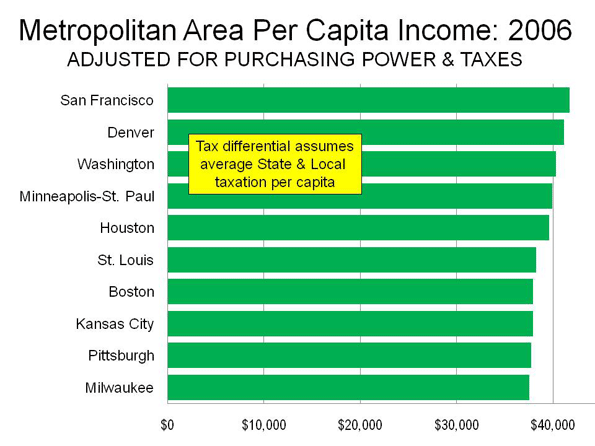

Those in post-industrial bastions tied to speculative capital – think Manhattan and the Hamptons – are the ones most benefiting from Obamanomics. College towns like Cambridge, Mass., Madison, Wis., Berkeley, Calif., and Palo Alto, Calif., will also prosper, becoming even richer and more self-important. It seems, then, that Obama has done best for elite graduates of Harvard and Stanford and other members of the “creative class.”

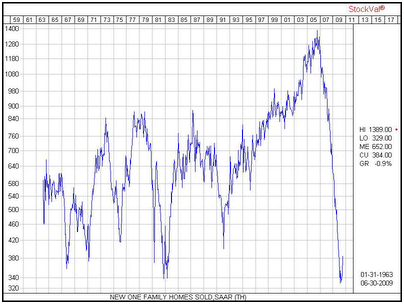

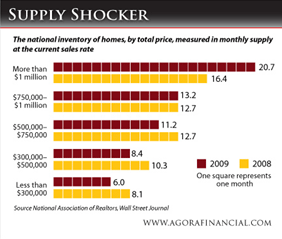

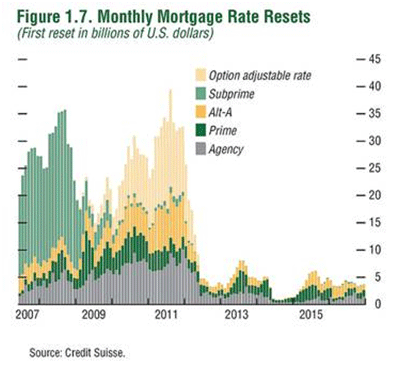

The rest of America, however, is still waiting for a real sustained recovery. Industrial and office properties remain widely abandoned not only in Detroit but Silicon Valley. The future sustainability of our economy depends mostly on what happens to those who previously staffed these facilities – those who produced actual goods and services – not just on a relative handful of people working at

3. Step on the Gas. Providence has handed America – and Obama – an enormous gift in the now recoverable deposits of natural gas found across the continent. Proven levels have been soaring and now amount to 90 years’ supply at current demand. More will be found, and across a wide section of the country.

Natural gas may be a fossil fuel, but it is relatively clean and thus the perfect intermediate solution to our energy problems. The problem: The president’s green advisers will seek to prevent developing these resources.

Although Obama should support strong environmental controls on gas extraction, the greens should not be allowed to block this unique and historic opportunity to shift economic power back to North America. Along with modest increases in domestic and Canadian oil, natural gas could end our dependence on fossil fuels from outside North America. This would relieve our military from the onerous task of defending other people’s oil supplies. But most important, the new energy sources could expand our industrial and agricultural economies so they can capitalize on the huge potential growth from markets at home and in the developing world.

The natural gas era could then finance continued research and deployment of renewable fuels. Let’s give it the 10 or 20 years that great transformations require. Quick fixes will lead us to subsidize the purchase of rapidly dated technology from China or Europe; we should aim at the energy equivalent of the moon shot, helping forge a huge technological advantage.

4. Rediscover America. As a candidate, Obama spoke movingly about his Kansas roots, but lately he seems to have become all big city all the time. This administration offers very little to people who live in places like Kansas, as many of my heartland Democrat friends complain.

Urbanites often forget that this is an enormous country. Crowded into dense cities themselves, they fail to look down from the window when crossing the country by plane. The vast majority of America is, well, vast – sparsely settled, if settled at all.

Moreover, Obama’s people need to understand that 80% of America live in suburbs or small towns. They do not want to live in dense cities or realize a move there would mean living in less than idyllic conditions. If Obama wants to shape a green America, he must find ways that work with the majority’s preferences.

But so far the president’s housing, transport and planning advisers seem to be pushing the death of suburbia and promoting ever more densification. It’s hardly surprising, then, that suburbs and small towns feel left out. After finally starting to inch toward the Democrats, they are now turning again to the right. If Democrats want to retain their majority, they need the strong support of these constituencies – without it the Congressional majority will be gone by the end of the second term, if not the first.

5. Chuck the Nobel; Embrace Exceptionalism. Many progressives love Obama because they see him as one of them in the struggle with what the immortal Bill Maher calls “a stupid country.” But the president should remind himself that the country may not be quite as dumb as it sometimes looks from Oslo – or from Dupont Circle, Cambridge or Soho.

Being smart was part of the reason the Republicans lost the majority. The voters understood the country was wasting resources – and young people – on internecine conflicts for energy that we could produce at home. The Bush years also undermined any GOP claim to fiscal responsibility.

Initially Obama allowed us to redefine American exceptionalism as something more than monomaniacal use of force and overconsumption. He spoke to our traditions of inclusiveness, adaptability and idealism. He offered the perfect vehicle because he and his story are so exceptional. Yet Obama sometimes seems more interested in serving as the apologizer rather than as commander in chief. His vision appears less American than pseudo-European.

This is not the path to success for American presidents. Whether Ronald Reagan or Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman or even Bill Clinton, a president has to be a spokesman for his country. Right now, on the world stage, Obama is looking more and more like Jimmy Carter.

I suggest these things because, for all his missteps over the past year, Barack Obama is my president and I want him to succeed. But to do so, first he needs to hit his own reset button – and the sooner the better. Unlike some, I do not believe the Obama presidency is already doomed. Presidents often grow in office: Despite his exceptionalism in other areas, let’s hope that Obama proves the norm here.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, will be published by Penguin Press early next year.

Official White House Photo by Pete Souza