Late this spring, when voters in California emphatically rejected tax increases to close the state budget gap, they sent a clear message to state policymakers. They were tired of California’s high taxes, which according to the non-partisan Tax Foundation, consumed 10.5 percent of state per capita income last year. This compared with a national average of 9.7 percent, making California the sixth most heavily taxed state in the nation.

But if Californians were tired of paying an additional 0.8 percent of their income in state and local taxes, what would they make of research by economists at the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis that estimated that the cost of living in California, based on 2006 data, was a whopping 29.1 percent above the national average? Obviously, from an economic point of view, the state’s high cost of living has a much greater impact on the average person’s standard of living than taxes do.

Cost of living is not an issue that we typically think about, when it comes to voting and politics. That needs to change. Cost of living estimates provide a valuable tool for making accurate comparisons of economic performance. Moreover, they provide the best available, if indirect, measure of the costs imposed by regulation. And with Congress debating potentially dramatic changes in how we regulate energy and health care, costs of this kind clearly deserve close scrutiny.

Let’s begin with economic performance, starting with California. According to 2006 census estimates from the American Community Survey, the median household income in California was $56,645. In terms of ranking, that made California the sixth most prosperous state in the nation. But how did California fare, once the cost of living was taken into account? The answer is not very well. The economists who published the 2006 data, Bettina Aten and Roger D’Souza, did not deflate income data by the full 29.1 percent when calculating the real effect of cost of living. Rather, they exempted certain components of income, such as government transfer payments. Using this attenuated calculation, real median household income in California in 2006 was $47,988. In terms of ranking, that dropped California down to 31st place. (Were the data deflated by the full 29.1 percent, the state would have fallen all the way to 48th place.)

California is not the only state afflicted with an exorbitant cost of living. Bluer than blue New York State, according to the Aten and D’Souza data, had an even higher cost of living, estimated at 31.8 percent above the national average. And not surprisingly, it fared particularly badly, once the cost of living was taken into account. Again using an attenuated calculation, the median household income in New York dropped from $51,384 in nominal dollars down to $42,744 in cost of living adjusted dollars. In terms of rankings, this dropped New York from 17th place down to 49th place. (Were the data deflated by the full 31.8 percent, the state would have fallen to last place, almost 10 percent lower than the next poorest state, Mississippi.)

What cost of living estimates taketh away from some, however, they also giveth to others. Consider, for example, Utah and Minnesota. In the case of Utah, median household income in 2006 stood at $51,309 in nominal terms. But according to the Aten and D’Souza estimates, the cost of living in Utah was 13.5 percent below the national average. Using the attenuated calculation, cost of living adjusted income in Utah was $57,147, the second highest in the nation.

In the case of Minnesota, median household income in 2006 stood at $54,023 in nominal terms. But according to the Aten and D’Souza estimates, the cost of living was 7.4 percent below the national average. The attenuated calculation put the Minnesota a cost of living adjusted income at $57,140, third highest in the nation.

As a general rule, the states with the lowest cost of living are states in the South and to a lesser degree the Mountain West. Among the states of the Old South, only Virginia had a cost of living above the national average. Dynamic states like North Carolina had a cost of living 13.1 percent below the national average. In Georgia, the figure was 12.1 percent. In the Mountain West, Idaho had a cost of living 17.3 percent below the national average. In New Mexico, the figure was 16.5 percent.

Besides affecting the true measure of economic performance, cost of living differentials have other, important implications as well. Federal taxes are one example. Consider New York. For years, it has been recognized that New York State sends more in taxes to Washington, D.C. than it receives back in the form of federal outlays. Recently, there has been some disagreement about the size of this deficit, but in the past it was generally agreed that it amounted to approximately two percent of Gross State Product. If New Yorkers were truly rich, this would not be a great burden. But as shown already, that is not the case. By failing to control its cost of living, New York ends up subsidizing other states that in real terms are doing much better.

Another implication of cost of living differentials has to do with population. All things being equal, people will live where they can maximize their standard of living. Not surprisingly, states that have seen the largest population growth in recent decades tend to be those with a low cost of living, notably in the South and in the Mountain West. On the other hand, states with a high cost of living have typically seen population growth lag. This is particularly true among certain Northeastern states that should have boomed, if nominal income were the best guide of how well a state is doing. Examples include Massachusetts, Connecticut and to a lesser degree, New Jersey, which has the second highest median household income in the nation.

In sum, the cost of living says a great deal about a state, its politics and its future.

Eamon Moynihan is the Director of the Cost of Living Project in New York. The purpose of the project is make New York City and State more competitive, with a particular focus on the costs imposed by regulation. A former government official at both the City and State level, he most recently served as Deputy Secretary of State for Public Affairs and Policy Development. An interactive website for the project can be accessed at thecostoflivingproject.org.

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.

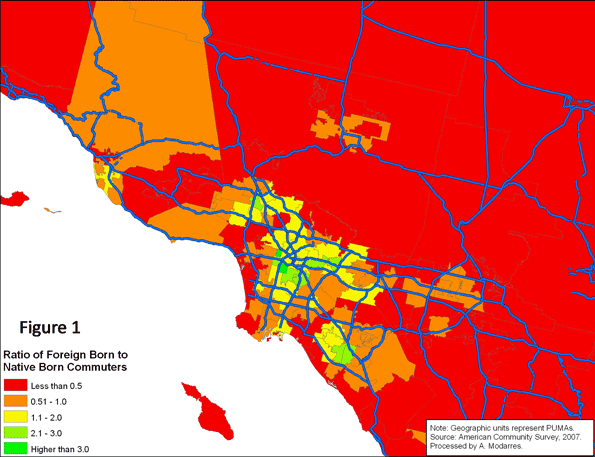

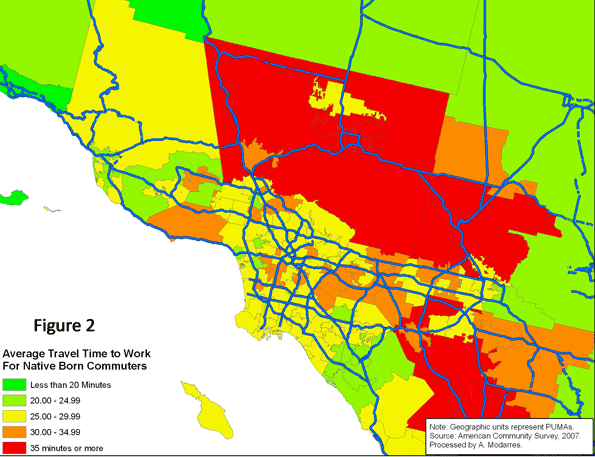

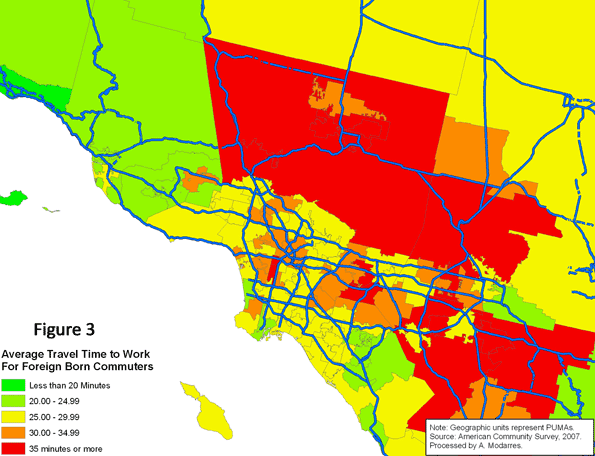

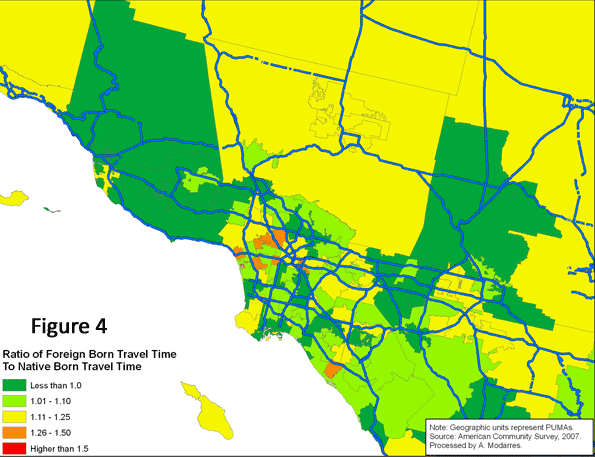

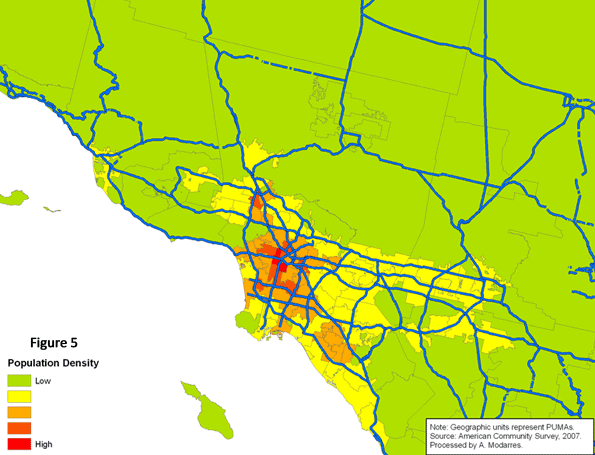

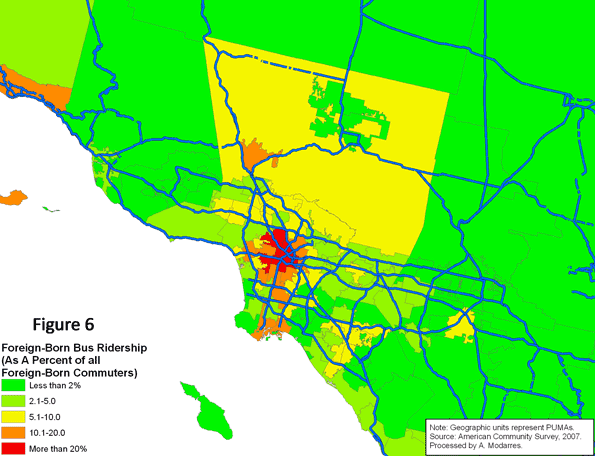

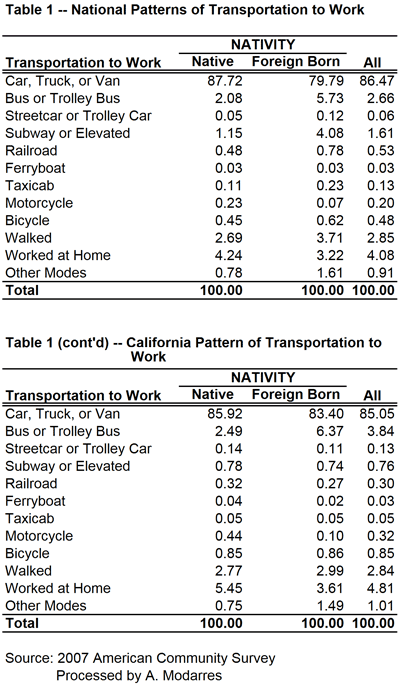

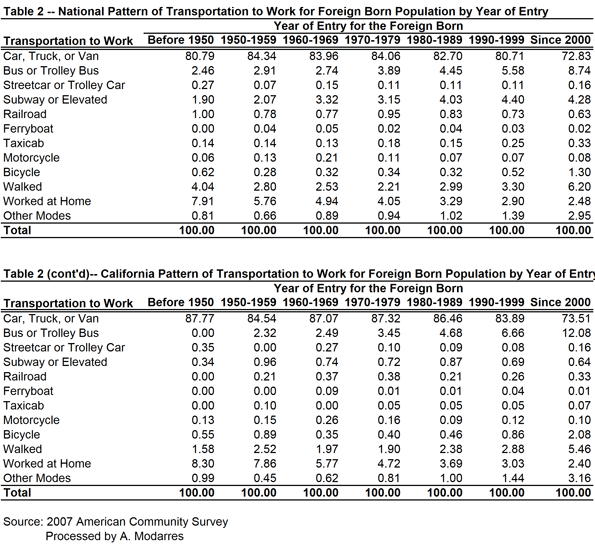

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.  Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

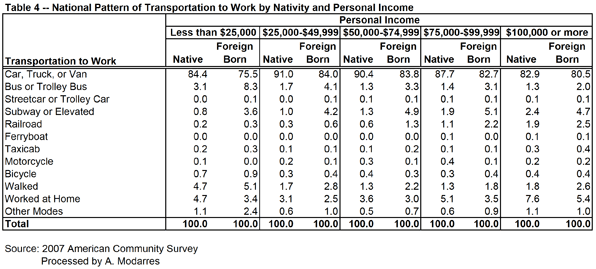

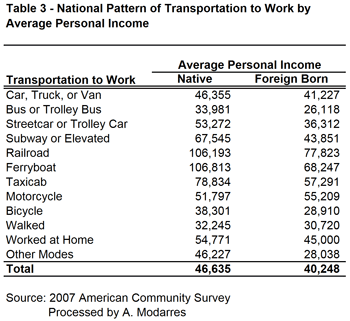

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.