During the first ten days of October 2008, the Dow Jones dropped 2,399.47 points, losing 22.11% of its value and trillions of investor equity. The Federal Government pushed a $700 billion bail-out through Congress to rescue the beleaguered financial institutions. The collapse of the financial system in the fall of 2008 was likened to an earthquake. In reality, what happened was more like a shift of tectonic plates.

History will record that the tectonic plates of our financial world began to drift apart in the fall of 2008. The scale of this change may be most evident in housing.

PART TWO – THE HOME BUILDERS

For decades, home ownership epitomized the American dream. For years, Americans saved their money for the required 20% down payment to purchase their dream home and become part of the great American Middle Class. They saved their money in a special account at the local savings & loan that paid a little more interest than the banks. Interest rates were fixed by law. A typical mortgage was written at a fixed rate for 30 years. Most American home owners stayed in their homes and celebrated the pay-off with a mortgage burning party.

In this arrangement, it was understood that the savings & loans were allowed to pay more interest because they provided long term home mortgages. They paid depositors 4 – 5% and lent money at 6% making a little profit on the arbitrage for their risk. With a 20% down payment, there was little risk. Mortgage bankers knew the homes they lent money on and more importantly, they knew their clients. The mortgage stayed on the books at the local savings & loan until paid.

In this time, home builders were mostly small local shops known by their customers and the lenders. For decades the industry was quite stable. Homes averaged 1,400 square feet in 1970 according to the National Association of Homebuilders. A quality home could be purchased for under $20,000. Not everyone could afford to buy a home but almost everyone aspired to this. Savings & loans provided 60% of all home mortgages.

The first crack in the dam appeared in the late 1970s. Under President Jimmy Carter, America suffered double-digit inflation. As the value of the dollar eroded, Americans sought investments that could protect their dollars from the ravages of inflation. Regulation D prohibited banks from paying interest on checking accounts. A tiny bank in Massachusetts, the Consumers Savings Bank of Worcester, Massachusetts introduced the NOW Account (Negotiable Order of Withdrawal) and began paying a higher rate of interest than the savings & loans. Money flooded into the bank.

The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 began the six-year process of phasing out limits on interest rate. Money flowed out of savings & loans and into NOW accounts and MMDA accounts (Money Market Depository Accounts). The S&Ls, with long term fixed loans on their books and short term money leaving for higher rates at the banks, never fully recovered. The primary source of funding for America’s home building industry was changed forever.

In the late 1980s the S&L industry attempt to recapture market share by entering the equity side of real estate development with disastrous consequences. The government was forced to seize most of the S&Ls and sell off their assets through the Resolution Trust Company (RTC). In 1989, Congress passed TEFRA, the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act that effectively outlawed direct ownership of property by S&Ls. It was a death blow to the industry and the end of the 30-year home mortgage as we knew it.

This is where the seeds of the current housing disaster and financial meltdown were sown. Wall Street and politics entered the financial vacuum left by the demise of the savings & loan industry. The Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 introduced the ARM (adjustable rate mortgage) which allowed rates paid to depositors to balance rates charged to borrowers. Our politicians, filled with good intentions, began down an irreversible path of using the home mortgage for social engineering.

Seeking to increase homeownership, Congress began to unwind the financial safety net that protected the American dream for nearly 100 years. An ugly brew was concocted with the marriage of too much money and too much power. Congress began to consider housing as a right instead of a privilege.

Over the ensuing quarter century, Wall Street and Congress conspired to turn the traditional 20% down, fixed 30 year mortgage on its ear. In 1977, they passed the Community Reinvestment Act that outlawed red-lining and forced lenders to make loans to poor neighborhoods. In 1982, they passed the Alternative Mortgage Transactions Parity Act (AMTPA) that expanded the funding and powers of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by lifting the restrictions on adjustable rate mortgages (ARM), balloon payment mortgages and the Option ARM (negative amortization loan). When a savings & loan made a mortgage in the past, they held it for 30 years or until paid. Freddie and Fannie became the new absentee owner of the majority of mortgages by purchasing them from the originators in the secondary market.

Thus the die was cast. Mortgage bankers and brokers became salesman and paper pushers packaging applications for the secondary market and financial investors who never saw the asset they lent money against or met the borrowers for whom they made the loan. But this was not enough to satisfy the greed of Wall Street which invented the CMBS (commercial mortgage backed security) in 1991. This was nothing more than a private label pool of mortgages that they sold off to equally unconnected financial investors in their own secondary market. Home mortgage lending by commercial banks went from nothing to 40% of the market in a matter of years.

The market could have possibly tolerated this bastardization of the conventional mortgage but neither Congress nor Wall Street could control themselves. There was simply too much money to be made. Congress determined that the credit score was discriminatory and violated the rights of the poor and minorities. In 1994, Congress approved the formation of the Home Loan Secondary Market Program by a group called the Self-Help Credit Union. They asked for and received the right to offer loans to first time homebuyers who did not have credit or assets to qualify for conventional loans. Conventional 80% financing was replaced with 90% loans and then 95% and finally 100% financing that allowed a home buyer to purchase a home with no down payment. The frenzy climaxed with negative amortization loans that actually allowed homes to be purchased with 105% financing.

In June of 1995, President Clinton, Vice President Gore, and Secretary Cisneros announced a new strategy to raise home-ownership to an all-time high. Clinton stated: “Our homeownership strategy will not cost the taxpayers one extra cent. It will not require legislation.” Clinton intended to use an informal partnership between Fannie and Freddie and community activist groups like ACORN to make mortgages available to those “who have historically been excluded from homeownership.”

Historically, a good credit score was essential to receive a conventional mortgage. Under pressure from the politicians, lenders created a new class of lending called “sub-prime” and as these new borrowers flooded the market, housing prices rose. Lenders used “teaser rates”, a form of loss leader, to help the least credit worthy to qualify for loans.

Congress instructed Fannie and Freddie to purchase mortgages even though there was no down payment and no proof of earnings by the applicant. An applicant could “state” his or her income and provide no proof of employment. Stated income loans eventually became known as “liar loans”. Sub-prime loans grew from 41% to 76% of the market between 2003 and 2005.

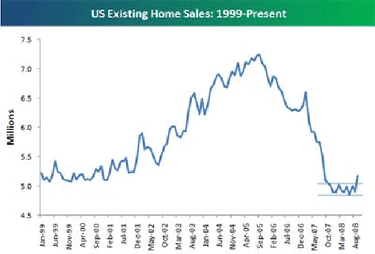

This devilish brew caused a record 7,000,000 home sales in 2005, including more than 2,000,000 new homes and condominiums. Mortgage lending jumped from $150 billion in 2000 to $650 billion in 2005. Prices rose relentlessly, pushed by more and more buyers entering the market. The top 10 builders in the United States in 2005 were:

- D.R. Horton – 51,383 Homes Built

- Pulte Homes – 45,630 Homes Built

- Lennar Corp. – 42,359 Homes Built

- Centex Corp. – 37,022 Homes Built

- KB Homes – 31,009 Homes Built

- Beazer Homes – 18,401 Homes Built

- Hovnanian Enterprises –17,783 Homes Built

- Ryland Group – 16,673 Homes Built

- M.D.C. Holdings – 15,307 Homes Built

- NVR – 13,787 Homes Built

Economists and pundits eventually began to identify the phenomenon as the housing bubble. And, bubbles burst. But Congress was not ready to confront reality. Rep. Barney Frank testified he “saw nothing that questioned the safety and soundness of Fannie and Freddie”. Fannie Mae Chairman Franklin Raines was paid $91.1 million in salary and bonuses between 1998 and 2004. In 1998 Fannie’s stock was $75/share. Today it is 67 cents.

In 2007 as prices stopped rising, the flood of buyers entering the market ceased putting market values into a free-fall. Home building is not a nimble industry. It takes years of planning and development to bring a project to market. America’s homebuilders had hundreds of thousands of homes and condos under construction when the housing market came to a crashing halt in the fall of 2008. New home sales, which topped 2,000,000 units per year in 2005, fell to an annual level of under 400,000 units in early 2009. Prices have retreated to 2003 levels and in some markets even lower.

What happens to America’s home builders? Do they follow General Motors and Chrysler into bankruptcy? Can they survive? New home sales are down 80% since 2005 – doing worse even than automobile sales. The tectonic plates of the housing industry are shifting rapidly and have not settled into any discernible pattern.

Residential land has dropped precipitously in value but a case can be made that raw residential land now has a “negative residual value”. There are hundreds of thousands of completed but unsold, foreclosed, and vacant, homes littering the countryside. The chart above demonstrates how dramatically sales have fallen since their peak in 2005. This “overhand” inventory must be cleared out before any recovery can ensue. The prices of these units must be cut by draconian margins to attract the bottom fishers and speculators who will take the risk from the home builders and purchase the outstanding inventory. This will not happen quickly. This is not a market that can generate an early rebound.

Has Congress learned from its mistakes? Apparently not. In March 2009, Democratic Representatives Green, Wexler and Waters introduced HR600 entitled “Seller Assisted Down Payments” that instructs FHA to accept 100% financing from those who cannot fund the required 3.5% down payment.

A year from now the landscape of America will be forever changed. Five years from now, will American ingenuity have revolutionized the home building industry? The imperative is to find homebuilders who can speed production and lower costs. And government needs to learn from its own mistakes and realize that a successful housing sector depends on solid market fundamentals as opposed to pursuing an agenda of social engineering.

***********************************

This is the second in a series on The Changing Landscape of America. Future articles will discuss real estate, politics, healthcare and other aspects of our economy and our society. Robert J. Cristiano PhD is a successful real estate developer and the Real Estate Professional in Residence at Chapman University in Orange, CA.

PART ONE – THE AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY (May 2009)