Back in the 1950s when I was growing up, pundits worried a lot about automation and the problem of leisure in a post-industrial society. What were the American people going to do once machinery had relieved them of the daily burden of routine labor? Would they paint pictures and write poetry? Armchair intellectuals found it hard to imagine.

It was the age of Ozzie and Harriet, when ordinary working and middle-class families could aspire to a house in the suburbs and a full-time Mom who stays at home with the kids. Today, of course, that popular version of the American dream is a thing of the past, especially the part about a full-time Mom who stays at home with the kids.

Ironically it was washing machines and automatic dishwashers – automation – that brought this idyll to an end. These two labor saving devices made it possible for housewives to go out into the workforce and compete with their husbands. At first they did it because they were bored at home and wanted to earn extra money, if only to help pay for those new household appliances. Gradually, however, it became a matter of necessity as two-paycheck families bid down wages even as they jacked up the price of suburban real estate in areas where the schools were good and the neighborhoods safe. By the time you subtracted the costs of owning a second automobile and using professional child care services, the advantages of that extra paycheck had largely disappeared.

The biggest surprise – to me as well – was that labor-saving technologies do not automatically redound to the benefit of labor. Other things being equal they reduce the demand for labor and hence its price in the marketplace. We saw this happen in the 19th century when modern agricultural machinery forced three-quarters of the population off their farms and into the cities, where they had to compete with immigrants and each other in the new industrial economy. Not until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1937, which outlawed child labor and established the 40 hour work week, did the world of Ozzie-and-Harriet become a democratic possibility.

But of course Modern Marvels never cease. Thanks to a never-ending supply of new labor-saving machinery, today’s industry employs only half as many people as it did in the 1950s when housewives first started entering the job market. Meanwhile medical science has greatly extended the average human lifespan, which has created a much larger pool of able-bodied adults who must either work or be supported by those who do. The Wal-Martization of retail and wholesale trade is yet a third development tending in the same direction.

Given this trajectory, perhaps it is time to consider a further reduction of the standard work week and the creation of new forms of suburban development. The goal would be for ordinary working families to begin enjoying the fruit of fifty years of economic and technological progress.

In particular let us consider the advantages of a program to build new towns in the exurban countryside in which people would be employed half-time (18-to-24 hours a week) outside the home, and in their free time would participate in the construction of their own houses, cultivate gardens, cook and eat at home, and look after their own children (and grandchildren) in traditional neighborhood settings close to village greens.

Once work and leisure are integrated into the fabric of everyday life people will not feel the same need to retire they do today. Instead of retiring in their sixties seniors could take easier jobs as they grow older and continue working for as long as they are able and willing. The Social Security crunch could be relieved without having to raise taxes on the younger generation.

We might even consider a return to the three-generation form of the family – except under two roofs instead of one, say, at opposite ends of the garden. Grandparents could use their savings to help their children with the initial purchase of their homesteads, while later on their children and grandchildren could help care for them in their old age, providing a more humane (and far more affordable) alternative to nursing homes and assisted-living arrangements.

And instead of being designed around high-speed automobiles the new towns could be small enough (25,000 to 30,000 inhabitants) and be laid out in such a way that the residents could get around on foot, by bicycle, or in “neighborhood electric vehicles” (souped up golf carts) designed to go 30 mph. In other words, with careful planning the efficiencies of urban density could be realized without forcing people to move back into the dense centers of our cities and surrounding both privacy and space.

I once hired the Gallup Organization to survey the American public about a lifestyle similar to this. The question asked was the following:

“As a new way to live in America, it has been suggested that we build our factories in rural areas outside the cities and run them on part-time jobs. Under this arrangement both parents would work six hours a day and three-days a week and in their spare time would build their own houses, cultivate gardens, and pursue other leisure-time activities. How interested would you be in living this way?”

Forty percent of the population said they would be either “definitely” or “probably” interested in the idea, with another 25 percent expressing possible interest. Included in these figures were two-thirds of those who had attended college, 60 percent of people with incomes in the top quartile, and 80 percent of African Americans.

Industries might be interested in the idea because part-time workers can work faster and more efficiently than full-time workers, just as in track and field the short-distance runners always run faster than the long-distance runners. When I explained this in a letter to one of America’s leading industrial relocation firms, the executive vice-president flew down to Tennessee the very next day to discuss it with me. He assured me that this was “a doable idea” and not “pie in the sky.”

Even so building New Towns in the Country is no easy task. It won’t happen spontaneously if for no other reason that people will not move to places where industry does not exist, and industry will not move to places where people do not live. It takes coordination, planning, organization, and investment in infrastructure.

There is a movement afoot in America for a new nation-wide infrastructure spending program. This proposal could be one part of it. After all, our federal government in the past has done things for the people to create a better way of life: the trans-continental railroad, the Homestead Act, the Interstate Highway System, the Fair Labor Standards Act, and the FHA.

New Towns in the Country and a much shorter work-week would work well together, even if the two things are impossible to achieve by themselves. We need to reorganize both time and space if we hope to create a healthy, productive way of life for tomorrow’s working families.

Luke Lea is a retired landscape gardening contractor and one-time professional carpenter. A graduate of Reed College, he lives in the small town of Walden, Tennessee, near Chattanooga where he was born.

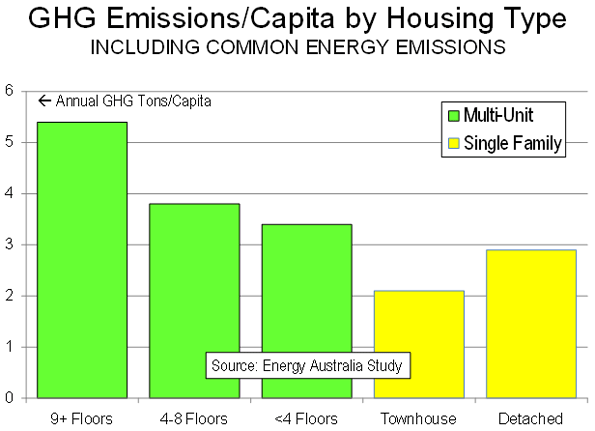

Forcing Density: Urban consolidation is destroying not only housing affordability, but also the character of Sydney itself. Sydney is an urban area of low density suburbs. It is also an urban area of high rise living. These two housing forms have combined with one of the world’s most attractive geographical settings to create an attractive and livable urban area.

Forcing Density: Urban consolidation is destroying not only housing affordability, but also the character of Sydney itself. Sydney is an urban area of low density suburbs. It is also an urban area of high rise living. These two housing forms have combined with one of the world’s most attractive geographical settings to create an attractive and livable urban area.