New Jersey Governor Chris Christie sent shockwaves through the transportation industry on last Thursday when he cancelled the under-construction ARC (Access to the Regional Core) rail tunnel under the Hudson River from New Jersey to New York (Manhattan).

The Governor accepted the Access the Regional Core (ARC) Executive Committee’s recommendation to “pull the plug” on the expensive project because of cost overruns. The project was to have cost $8.7 billion, but could escalate up to $14 billion according to the Governor’s office. All of any such cost overrun would have to be absorbed by the state of New Jersey, which like many other states is in dire financial straits.

Christie said:

“I have made a pledge to the people of New Jersey that on my watch I will not allow taxpayers to fund projects that run over budget with no clear way of how these costs will be paid for. Considering the unprecedented fiscal and economic climate our State is facing, it is completely unthinkable to borrow more money and leave taxpayers responsible for billions in cost overruns. The ARC project costs far more than New Jersey taxpayers can afford and the only prudent move is to end this project.”

Governor Christie indicated that the project could become New Jersey’s “Big Dig,” referring to the Boston highway project that he said escalated in cost by 10 times (that is not a typo).

Yet supporters of the tunnel were unanimous in their condemnation of Christie’s move, from Paul Krugman of The New York Times to the Regional Plan Association.

New Jersey Senator Frank Lautenberg announced that Christie had backed down, noting his “reversal of yesterday’s decision to kill” the tunnel project. Referring to a meeting between US Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood and Governor Christie, Lautenberg said “The Secretary was clear with Governor Christie: if this tunnel doesn’t get built, the three billion dollars will go to other states. We can’t allow that to happen.” Lautenberg listed a litany of benefits such as a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 70,000 tons annually. He also noted that New Jersey would have to reimburse the federal government the $300 million it had received for the tunnel. Senator Robert Menendez added that “New Jersey taxpayers don’t want to own a $600 million hole to nowhere.”

However, under examination, it is unclear whether Christie had “reversed” his position. Christie agreed to consider “options to potentially salvage” a tunnel project based upon options (not made public) offered by LaHood. New Jersey and Federal officials will be meeting on the matter over the next two weeks. Christie, however, reaffirmed his concern about project finances, stating that” the ARC project is not financially viable “ and its expectation “to dramatically exceed its current budget remains unchanged. ” The Newark Star-Ledger cited state officials as saying that the decision does not represent a reversal of Christie’s original decision.

Thus, everything may be up in the air. Given that, here are a few issues the state of New Jersey may like to consider as it finalizes its decision:

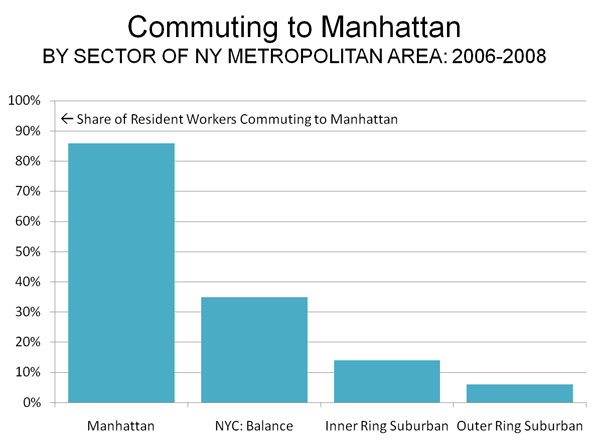

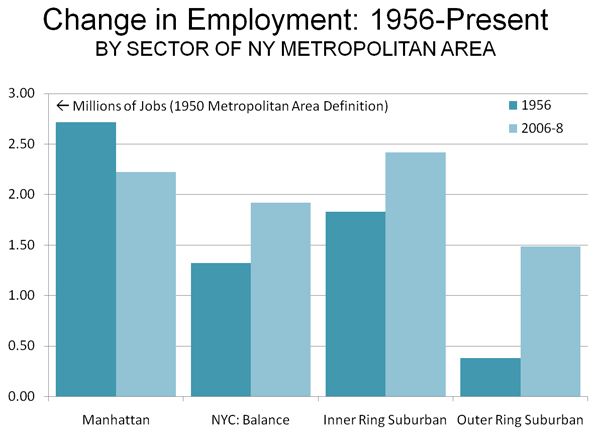

1. Exaggerating the Need for the Project The new rail tunnel is to serve a purported increase in commuter rail ridership to Manhattan jobs in the future. The project’s Final Environmental Impact Statement says that Midtown Manhattan’s employment will grow from its present 2.6 million by another 500,000 by 2030. This is unlikely. Manhattan’s entire employment (not just Midtown) peaked at 2.4 million in 2008. One might expect the planners could have gotten something so simple correct. Manhattan employment remains below 2001 levels and never rose more than 35,000 even at the peak of the last boom (annual figure, from 2001). The consultants also are projecting a 1.6 million population increase west of the Hudson River (New Jersey suburbs along with the New York counties of Rockland and Orange) by 2030. However, the New Jersey and New York metropolitan counties to the west of the Hudson are more likely to grow only 1.1 million, based upon official state projections (Note). The questionable population and employment projections reveal that the “need” for the new tunnel may have been grossly overstated.

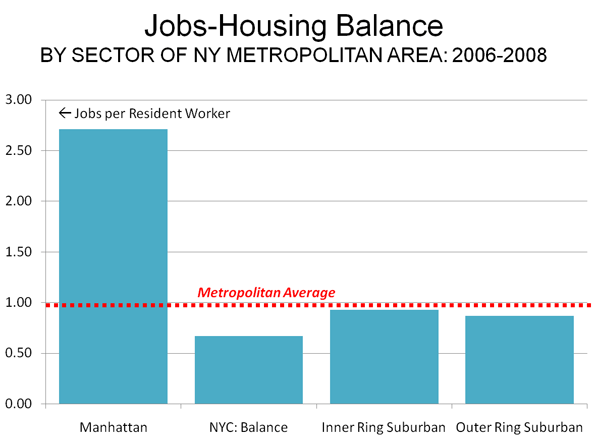

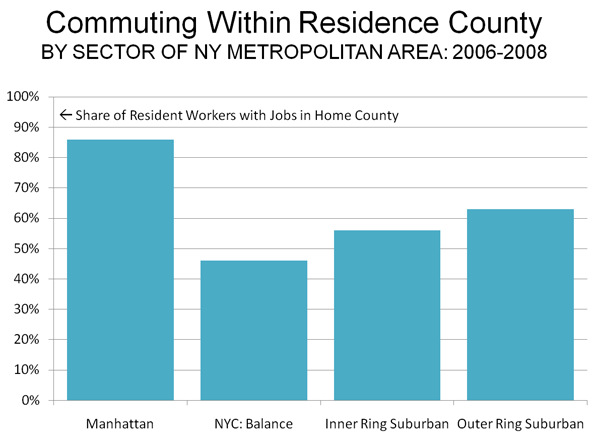

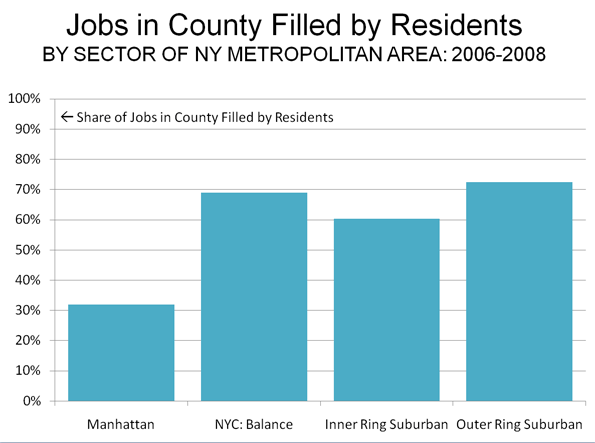

2. Exporting New Jersey Jobs to New York Why should New Jersey pay to build more capacity so that its people can work across the state line? Why should they not work in New Jersey? New Jersey is often thought of an economic afterthought in Manhattan centric media and business interests (such as by The New York Times). In fact only a small share of New Jersey commuters travel to Manhattan for work. Even in the New Jersey counties that border New York, only 12% of commuters work in Manhattan. In the other New York metropolitan area counties in the metropolitan area, the figure drops to 5%.

The trends here are also important. Since 1956, every new job in the New York metropolitan area has been created outside Manhattan (Manhattan’s employment is 400,000 lower now than back then). New Jersey depends on New Jersey far more than it does New York. New Jersey has developed successful new office complexes in Jersey City, New Brunswick, along the I-287 Belt Route and elsewhere. Perhaps New Jersey should seek to minimize work trip lengths and encourage the next 500,000 jobs to be created in the state rather than in New York. Downtown Newark, for example, has excellent transit access and could use substantial new employment investment. This might prove more beneficial for New Jersey and its taxpayers.

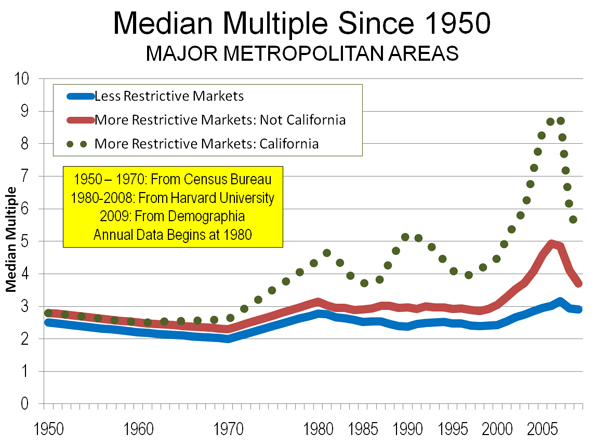

3. Costs Could Rise Even Higher The tunnel could easily climb in cost beyond the now feared $14 billion. Big Dig cost escalation continued almost to the project’s opening. There is no reason to expect it will be different with the Hudson tunnel. It has been reported that one of LaHood’s options is simply to lower cost projections. New Jersey should buy that option only if the federal government underwrites all of the cost overruns. However, such a deviation from federal policy would bring stiff opposition from other parts of the country.

4. The Cost of Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions Like so many transit projects, the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is raised as a benefit of the tunnel. But at what cost? Each of the 70,000 annual tons of greenhouse gas emissions removed would require a capital expenditure of $16,000. The present market price for greenhouse gases is $20 per ton. New Jersey could accomplish the same objective for just $1.4 million annually.

The Decision Much rides on Governor Christie’s decision. It may be better for the state to have a $600 million tunnel to nowhere than a $14, $20 or $25 billion tunnel that may not really be needed. Moreover, frustration is building with Washington’s “plunder” philosophy that encourages wasting money at home, so that another state doesn’t get the chance. Digging the nation out of its present (and future) malaise seems likely to require fresher thinking than this.

If Governor Christie musters the courage to stop this project now, it could be a shot across the bow of an international vendor and consulting engineering community that has routinely low-balled costs only to later jack them up, confident that no project would be canceled once started.

——–

Note: This figure is derived using New York 2030 projections and New Jersey 2025 projections, increased by the 2020-2025 growth rate to project 2030 population.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photo: Hudson River looking south between Lower Manhattan and Jersey City (photo by author)