Getting out was essential but I was stuck in Brooklyn until I could plot my escape…

There was no such thing as “diversity” in white, working-class Bensonhurst in the 1950s. Only the Jews and the Italians.

My tribe descending from Yiddish-speaking East European immigrants who settled in cramped tenements and worked in the schmatta trade of Manhattan’s lower east side.

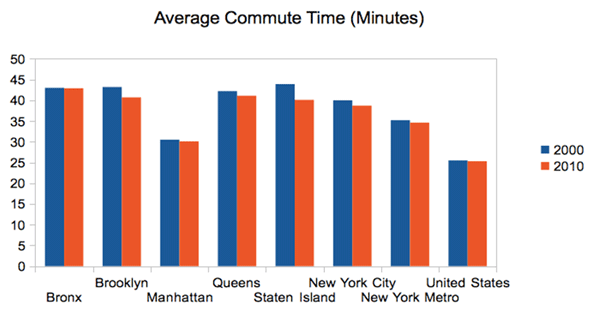

Moving – after the war – across the East River to apartments with bedrooms and bathrooms; a 50 minute commute to “the city” on the west end line of the BMT. Sharing the neighborhood with Southern Italian Catholics, a few Irish and fewer blacks and Puerto Ricans who worked for – but rarely lived among – us white “ethnics.”

My father drove a cab six days a week and my mother typed for a living. We weren’t poor but sometimes for dinner my mother would serve macaroni with ketchup. Sally and Irv enjoyed themselves occasionally – they played penny poker with friends on Saturday night, she watched Liberace, he watched the Yankees, and now and then they would go out for “Chinese.”

But much of the time they were frustrated and miserable. Irv was known to friends and cousins as “easy going” and – though he didn’t drink – could “snap” and do a lot of damage. Sally was always worrying and felt ashamed of her divorce in the 1940s. Her daughter, my “half” sister, twelve years older, lived with us and hated my father (for good reason).

I was acting out at home – yelling, cursing and defiant – and in junior and senior high: cutting classes and on my way to becoming an official “truant” and dropout. In the grip of adolescent anguish, by 14 I would ruminate incessantly about girls, particularly the local Italians, whose appeal was intensified by a taboo that would prevail into the 1970s and beyond.

Even my pre-pubescent preferences leaned in that direction, stimulated by those lusty Italian ladies of Bensonhurst. Cleavaged, tight-skirted and toe-nail polished, they seemed more overtly libidinal than the Jewish women in the neighborhood. My fascination was a distraction from family problems and a way to imagine my escape. I enjoyed other diversions, as well: scooting around the corner to play punchball or pedaling my bike to the Cropsey Avenue Park or buying an egg cream – for twelve cents – on Bay Parkway and 86thStreet.

Rivalries erupted from time to time between the Jewish and Italian boys. I was involved in some of these courtyard fist fights. Though the violence was minimal (no weapons: just a few punches in the face, a headlock and then a submissive “I give.”), these neighborhood battles would not only contest virility but would reveal an ethnic-based class resentment.

While many of my Italian peers became very successful academically, professionally and financially, it was the Jewish kids who were most eager to leave the old neighborhood (this is decades before the borough became trendy for Gen X bohemians). This ethic of upward and outward mobility, built into Jewish cultural DNA, has fashioned a Jewish-American Diaspora – from Hester Street to the “outer boroughs” to the upper west side, Hempstead Long Island, Southern California and points in between.

For a time, I resisted the traditionally available route for a smart Jewish kid to get ahead. Depressed and anxious, I was flunking out of school. Developing instead the style of free spirit, a malcontent and a wanderer; a persona which required that I reject my parent’s values with a simplistic, snotty and condescending critique of them as vacuous and conventional.

This fit right in with “generation gap” rhetoric and prevailing notions of liberation pulsing through the counter culture in 1967. I could distance myself from my painful past and pathetic parents, disparage their “material values” – appalled, for example, by their choice to cover their sofa with clear, thick, sticky plastic – and fashion myself as superior.

It would take awhile before I would better understand how my parent’s lives shaped my political values. By my late teens I saw as merely incidental the fact that they had joined the ranks of New York’s unionized civil service. My father was forced out of taxi driving by his health, becoming a clerical for the state insurance fund; my mother putting her fast fingers to work for the city’s board of education.

But a lonely 17-year-old had no time for such reflections. On nights when I had trouble sleeping, I would slink out of my parent’s apartment to wander the streets. There was always the faint hope of an exotic sexual encounter, but most of these three-in-the-morning outings were a time for thoughtful solitude.

Walking past the Coney Island Terminal – the last stop for Brooklyn-bound trains from Manhattan – just a few blocks from the Atlantic Ocean and the famous Boardwalk, Aquarium, Cyclone and Nathan’s, I was ruminating over my academic circumstances.

In a few hours, I would be starting a new high school. (My parents and I had, in fact, deserted Bensonhurst – but only barely – relocating a few neighborhoods south to Brighton Beach which, ten years later, would take in thousands of Soviet émigrés and gain national fame as “Odessa by the Sea.”)

I stayed up all night, walked along Surf Avenue as far as “Seagate,” (one of America’s oldest gated communities on the western edge of Coney Island) and – somewhere along the way – decided to stop screwing around in school.

I could tell this was a big deal. Later in life when I started to chart these pivotal events, I would mark my Surf Avenue expedition as the first of many.

That semester in Lincoln High I stuck to my resolve, dropping bookkeeping and merchandising, flipping back to a college prep curriculum, re-taking failed classes – geometry, biology – and planning an extra year in high school.

Though I would finish Lincoln with a weak overall record, my academic performance improved substantially the final two years – enough to let me shop around for a college which would recognize my potential.

The last stop on my exit from Brooklyn would be the NYU psychology clinic for nine months of analytic psychotherapy with a grad student who would later become a successful New York analyst. Nowadays, concerned and proactive parents who detect problems in their kids are quick to refer them to psychologists for therapy and psychiatrists for medication. But this was my initiative and I jumped at the chance to see a “shrink.” Twice a week I rode the subway into lower Manhattan and – for 50 cents a session – began what would be decades of various forms of psychotherapy (including a brief period in which I aspired to be a therapist myself).

Coincidentally – and ironically (given my ultimate career choice) – in 1970, the NYU psychology clinic building was located at 23-29 Washington Place which, 60 years earlier (then known as the Asch Building) was the site of the Triangle Shirt Waste Factory fire which killed 146 immigrant garment workers – mostly young Jewish women.

I didn’t find out until years later that the building held such enormous historical significance; that this epic tragedy – which triggered fire code and workplace safety reforms across the country – took place at the spot where I was preparing for my life as an adult.

Though oblivious to quite a bit happening around me (preoccupied with, among other things, overcoming my awkwardness with girls), I was however starting to absorb some of what was going on in the world.

I could recount stories here about my cultural and political “awakenings” – tying my personal development to iconic historical events: the M.L. King and Bobby Kennedy killings, Woodstock (I was there), the Democratic National Convention police riot (I wasn’t there) – but I’ll save for another time my detailed reflections on this period in American culture and politics. Hasn’t enough already been said about how sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll changed our lives?

Though I was linked to prevailing counter-culture sentiments – appropriately appalled by the War in Vietnam and other U.S. “atrocities” – my political views were confined (or should I say restrained) by a mainstream liberal tendency that I’ve maintained to this day.

Sure I was impressed by Ivy League SDSers taking over the dean’s office – I respected their dedication to social causes (and the fun they seemed to be having). But my own working-class resentments may have been surfacing in reaction to what was then perceived – not always correctly – as the “privileged” student protesters of American middle class families.

My working-class “liberal populism” reflected my parent’s political values pretty closely (though I couldn’t know this at the time). One example would be my lack of resistance to Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential. The “no difference” argument didn’t hold as I lined up happily with New Deal Labor Dems to try to beat Nixon.

I also took an intense interest in the reform movement in Eastern Europe against communist totalitarianism. While I assume most American liberals and radicals at the time aligned with Czechoslovakians in their protest against Soviet tyranny, I felt a particular affinity for the young reformers. My revulsion to Soviet Communism was sealed for life when Russian tanks and troops crushed Alexander Dubcek’s Prague Spring.

I don’t want to make too much of all this – I was just a kid – but I always felt a slight pull to the political center and couldn’t quite wrap my head around radical-chic notions about the Panthers, Mao or a range of utopian ideas espoused by elements of the new left. Though I might have looked like one, I was not a revolutionary.

Twenty years later, I would find a very nice fit within the American Labor Movement, navigating comfortably among the so-called old guard and the new generation of union militants. I would develop a revisionist view of Sally and Irv, less critical of their values and more appreciative of how a few extra dollars in their pockets – thanks partly to the New York public sector unions – could make a big difference in workers’ lives.

I would also take on a more balanced – you could say compromised – view on the potential for personal transformation and social change. Economic conditions do shape peoples lives, but individual choice enters the mix. America – at its best – gives you a shot (at least it used to) and you make of it what you will.

As a Brooklyn, working-class, Jewish American – introspective and inclined toward progressive (but practical) politics – I feel lucky to have come as far as I have.

I’ve spent my life trying to overcome an agitated mother and angry father. By 10, I was bratty and foul-mouthed; by 13, sexually-fixated and withdrawn; by 16, defiant and delinquent. To compensate, I would develop very subtle behaviors to conceal my feelings of isolation.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. By the end of the 1960s, these formations were incubating. In the 1970s I would work on my narrative: success on my own terms and an ongoing struggle for American justice and personal salvation.

I would also figure out that blaming parents or “society” for low self-esteem – even if it opens the door to self-acceptance – can only take you so far.