For over a generation pundits, policymakers and futurists have predicted the decline of the American family. Yet in reality, the family, although changing rapidly, is becoming not less but more important.

This can be traced to demographic shifts, including immigration and extended life spans, as well as to changes of attitudes among our increasingly diverse population. Furthermore, severe economic pressures are transforming the family–as they have throughout much of history–into the ultimate “safety net” for millions of people.

Those who argue the family is less important note that barely one in five households–although more than one-third of the total population–consists of a married couple with children living at home. Yet family relations are more complex than that; people remain tied to one another well after they first move away. My mother, at 87, is still my mother, after all, as well as the grandmother to my daughters. Those ties still dominate her actions and attitudes.

Critically, marriage, the basis of the family, is also far from a dying institution. Sociologist Andrew Cherlin notes that over 80% of Americans eventually get married, often after a period of cohabitation. Later marriages are also reflected in later childrearing. Younger women today may be less likely to have children, but far more older women are giving birth; since 1982 the number of those over 35 who give birth has more than tripled. This trend has accelerated and will continue to do so given advances in natal science.

More important, people continue to value the stability and cohesion that only families can provide. According to social historian Stephanie Coontz, Americans today are more likely to be in regular contact with their parents than in the past. Some 90% consider their parental relations close, and far more children are likely to live with at least one parent now than they were as recently as the 1940s.

To be sure, as Coontz makes clear, the 21st-century family will not reprise the Ozzie-and-Harriet norms of the 1950s. Everything from divorce to immigration and gay marriage is reshaping family relations. While Americans may “swing back” to a more family-oriented society, social historian Alan Wolfe notes, “it will be with a difference.”

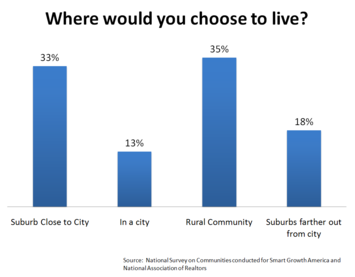

But family will remain the central force that informs our communities and economy. For example, when people move, a 2008 Pew study reveals, they tend to go to areas where they have relatives. Family, as one Pew researcher notes, “trumps money when people make decisions about where to live.”

Perhaps nothing better illustrates this trend than the increase in multigenerational households. As people live longer and produce offspring later, family ties are strengthening. A recent Pew survey reveals that the number of households accommodating at least two adult generations has grown in recent years. Today the percentage of such multigenerational households–some 16%–is higher than any time since the 1950s and swelled by some 7 million since 2000. At the same time, the once rapid growth of single-person households, which nearly tripled since the 1950s, has begun to slow and, among those over 65, has declined in recent years.

Rather than be hived off in isolation, grandparents are playing a larger role in family life, both as financial supporters and as sources of reliable child care. Living with or being close to grandparents is particularly important for younger Americans, many of whom are struggling to raise families in expensive regions such as New York or Los Angeles. As Queens resident and real estate agent Judy Markowitz puts it, “In Manhattan, people with kids have nannies. In Queens, we have grandparents.”

As these caregivers age, in turn, they will require help for themselves. One welcome change, already evolving, is the number of older adults moving in with their children. Institutionalized care for people over 75, once seen as inevitable, has dropped since the mid-1980s, as more families hire part-time help or have aging parents move in with them.

Today as many as 6 million grandparents live with their offspring, allowing, by one estimate, as many as half a million people to avoid nursing homes. Between 2000 and 2007, according to the Census Bureau, the number of people over 65 living with adult children increased by more than 50%. One California builder reports that one third of new home buyers want a “granny flat,” an addition to accommodate an aging parent. Roughly one third of American homes have the potential to create such units. In the coming decades homes that can be adapted to the changing needs of families will become an increasingly desirable commodity.

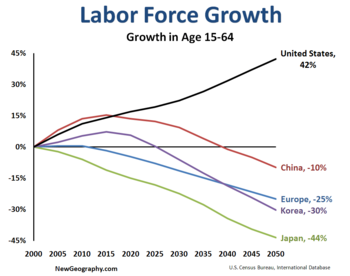

Arguably the strongest force for continued importance of family comes from the two groups, ethnic minorities and millennials, who will shape the next few decades. Immigrants, particularly Latinos and Asians, are also far more likely to live in married households with children than are other Americans. They are also more than twice as likely, according to Pew, to live in households with at least two adult generations.

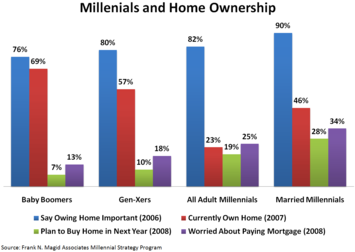

The other key group will be the millennials, those Americans born since 1982. As noted generational researchers Morley Winograd and Mike Hais suggest in their landmark book Millennial Makeover, the rising “millennial” or “echo boom” generation–those born after 1983–enjoy more favorable relations with their parents: Half stay in daily touch, and almost all are in weekly contact.

The millennials, Winograd and Hais suggest, generally do not share the generational angst that defined many boomers. Indeed three-quarters of 13-to-24-year-olds, according to one 2007 survey, consider time spent with family the greatest source of happiness, rating it even higher than time spent with friends or a significant other. And they seem determined to start families of their own: More than 80% think getting married will make them happy, and some 77% say they definitely or probably will want children, while less than 12% say they likely will not.

The current tough economic conditions may be slowing family formation but is clearly bolstering close, long-term ties between children and parents. One quarter of Gen Xers, for example, still receive financial help from their parents, as do nearly a third of those under 25.This trend has been mounting since well before the recession. Ten percent of all adults younger than 35 told Pew researchers last year that they had moved in with their parents over the past year.

Higher college debts, high home prices and a less-than-vibrant job market could all extend this virtual adolescence in which children maintain strong ties of dependence into adulthood. Although these conditions may increase support for more governmental assistance among some, young people are finding out there’s one institution that, despite political shifts, really can be counted on: the family.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in Febuary, 2010.

Photo: driki