Real estate broker Coldwell Banker handles corporate relocations for a large portion of our middle class. It recently released a survey of Suburbanite Best Places to Live. While it’s easy to dismiss as a sales tool for their realtors, the survey provides a fascinating glimpse of middle class, suburban preferences, influenced by our current economy. Coldwell Banker’s top honors go to Cherry Hills Village, Colorado, a suburb of Denver. Suburbs of Seattle, New York City, Washington, DC, and other prominent cities feature strongly on Coldwell Banker’s list, which highlights places that are sprinkled evenly throughout the United States. Notably missing are any communities in Florida.

For a state with sunshine, beaches, and low taxes, Florida just doesn’t have the chops to get even one community onto the top 100 list.

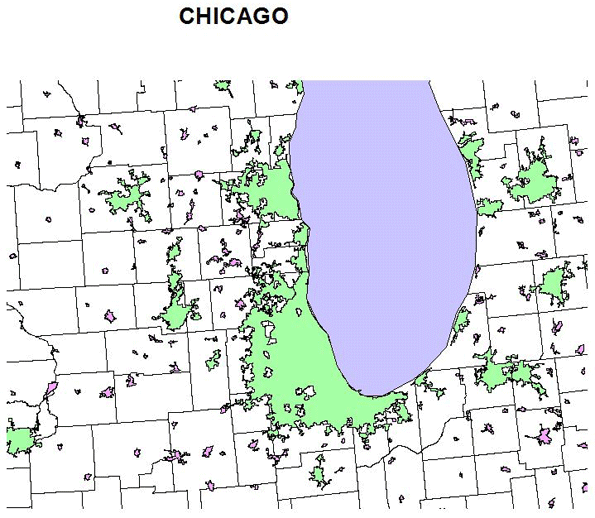

Weather, evidently, has little to do with our middle class’s desirable locations. Frigid Whitefish Bay, just south of Milwaukee, captured spot #100. Situated along the shore of Lake Michigan, this suburb of 14,000 doesn’t exactly have the kind of weather that makes people flock to the beach. Instead, it offers residents a strong sense of community, heritage, and a culture that values education and family. If you move here, you’ll find yourself within a suburban community with a high homeownership ratio, an educated population, and a quality of life that includes short commutes, low crime rates, close conveniences, and a tendency to eat at home.

Suburban living has maintained a strong appeal for middle-class Americans due to the popularity of many of the factors on which Coldwell Banker based its rankings. While socialites prefer more urban, dense lifestyles (which is another list that Banker recently produced), suburbanites prefer backyards and quieter neighborhoods away from the hustle and bustle of the city; they don’t need to be near the action. Florida has all these things in abundance, except when compared to… almost everywhere else.

Windermere, Florida’s top ranked suburb, came closest, ranking just below Whitefish Bay and a couple of others. Like most suburbs on the list, Windermere is on the periphery of a large metropolitan area (Orlando), and contains conveniences, good schools, parks, and recreation facilities.

For much of its history, Florida represented the suburban American dream. The net benefits included an affordable cost of living and upward mobility, and Florida’s growth has consisted almost entirely of suburban densities. No one can accuse Florida developers of building communities that people didn’t want – the product was carefully researched to fit the market.

In the late period of the boom, urban options were also developed, in the belief that a new demand for socialite “downtown” style living would emerge. Townhomes and condominiums rose in Florida’s primary and secondary urban markets. Even tertiary cities like Sanford, a historic agricultural town north of Orlando, begot a six-story condo. Those who migrated from Chicago and the dense Northeast now had a diverse set of choices, from rural to urban, with something to please everybody.

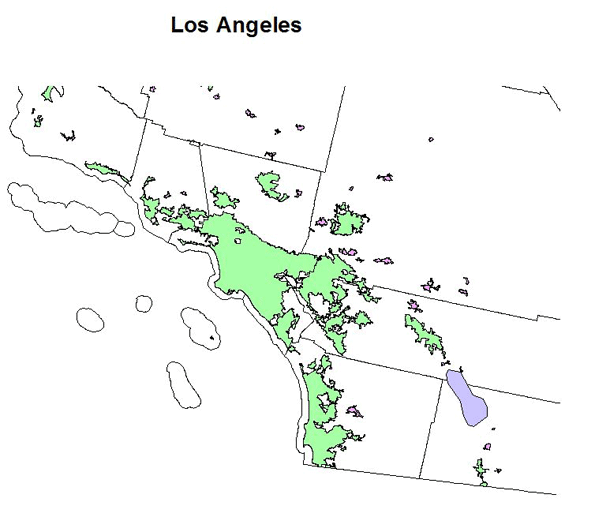

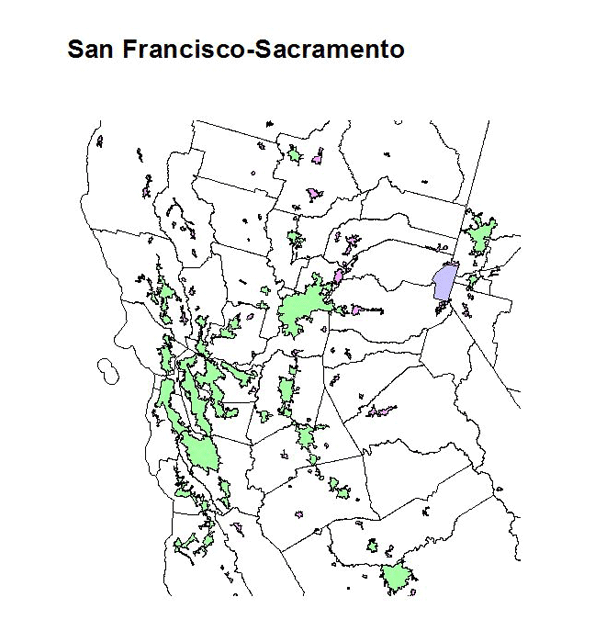

It is perhaps this dilution of the market that has made Florida’s star fade a bit in relation to the national constellation of suburbs. If East Grand Rapids, Michigan (Coldwell Banker’s #8) can outrank the hundreds of suburbs around Tampa, Miami, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, and Orlando, there’s something else going on besides beauty.

One thing that many of the top 100 have in common is a strong public education system. Florida, which has refused to invest in education, may now be harvesting the bitter fruit of this stubborn negligence. The state’s primary growth today continues to be in retirees who are uninterested in supporting education, and who control a large part of the state’s political power.

Another aspect that the top 100 suburbs offer is safety. “Safety is a priority,” states the opening page of this survey, but it simply isn’t something that most people associate with the Sunshine State. A state that doesn’t offer a strong sense of personal safety isn’t going to rank highly, no matter what else is being offered. With two out of the ten most dangerous cities in the country, Florida seems more like the wild West than a suburbanite’s dream come true.

Increasing public safety and public education are two efforts that government can do best, most people agree. Florida has spiraled downward on both fronts. The state’s leadership, by cutting taxes during the worst part of the recession, haven’t exactly helped the situation. With Florida’s new home sales up, the state’s economists are whistling a happy tune, convinced that the worst is over. But what Coldwell Banker is telling Florida is a different, darker story.

Florida’s best offerings are attracting a population less interested in the core values stated in the Coldwell Banker survey – safety, good education, a sense of community – and so we continue to get more of the same. More population that reinforces Florida’s lack of investment in community, more population reluctant to put money into education, and more population that is quick to move somewhere else at the earliest opportunity seem to be Florida’s fate. This represents a lost opportunity to those who wish to see Florida make gains in these spheres – education, community, and safety. And it represents a lost opportunity to match up a truly beautiful place with truly involved people.

Corporations seeking to relocate and recruit good people pay attention to these surveys. Florida’s low taxes may lure a few more down south, but if corporations need to attract and retain top talent, this survey points to where they are likely to go, regardless of the incentives our state has to offer.

Places like Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin; Rossmoor, California; and Haworth, New Jersey will continue to gain in the type of population that share these same values. The middle class, fighting its way back from a threatened extinction, isn’t likely to take a chance on a place that has a rapidly degrading quality of life. Until Florida’s culture starts caring about the quality of its community, safety, and education, our state will continue to grow without flourishing as a place where people desire to be.

Richard Reep is an architect and artist who lives in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and he has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

Bigstock photo: Florida Housing