Despite the claim to uniqueness that is quintessentially French, the housing bubble shares the same root as we see in the Anglo-Saxon world. To be sure, some analysts blame it only on low interest rates: they made the households more solvent, and thus drove home prices up. This rise in purchasing power might have been enhanced by some specific subsidies to new rental units. Some also y point to normative constraints on new buildings have added to production costs.

These facts are undisputed, but a demand-only driven bubble can’t happen in a really free market where price signals provide incentives to supply more units, moderating price escalation, and eventually revert the price curve. After all, there hasn’t been anything like a “car price bubble”. So there has to be a supply side factor constraining the building of new homes. And since building itself doesn’t require scarce skills, the constraint has to come from land. These analysts observe that in middle America booming cities like Texas’ Houston and Dallas, or others in Kansas, Georgia, Oklahoma, and elsewhere didn’t experience such a price bubble despite identical credit conditions, despite in some cases, as in Texas, an even greater surge in demand.

Numbers

Let’s take a look at official French statistics.

Professor Joseph Comby (From Institut d’Urbanisme de Paris) summarizes essential data in an exhaustive article (not available online) published in the very specialized peer reviewed "Revue Foncière" (n°3, January 2015), dedicated to land and housing issues. His graphs can be accessed from data provided by our national institute of statistics (INSEE).

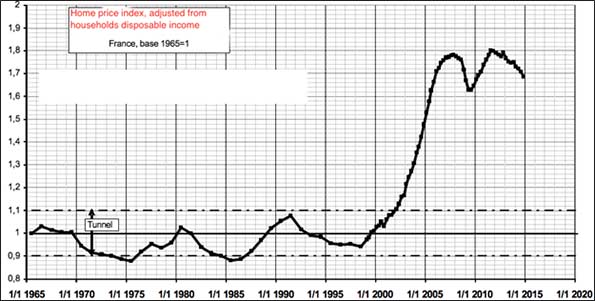

The first graph shows that home prices surged between 1997 and 2007, and that the prices didn’t really slump then, despite worldwide economic crisis. Average home price rose by a whopping 150% in 11 years, and rose 86% faster than households’ disposable income.

Fig 1. Home price Index, adjusted from households’ disposable income – Base 1, 1965.

Source: French Ministry of Sustainable Development (doc format)

In this period, the median multiple in France (Average Home price / Average Household disposable income) rose from a stunningly low 2.25 to 4.21, and these average figures hide numerous regional discrepancies.

Home prices can be truncated between land costs and building costs, including the home and the infrastructure costs (road access, sewage, water and energy adduction, and so on). Had this price hike uniquely "credit and demand" driven, we should have seen a relatively parallel evolution between land and building components in home prices.

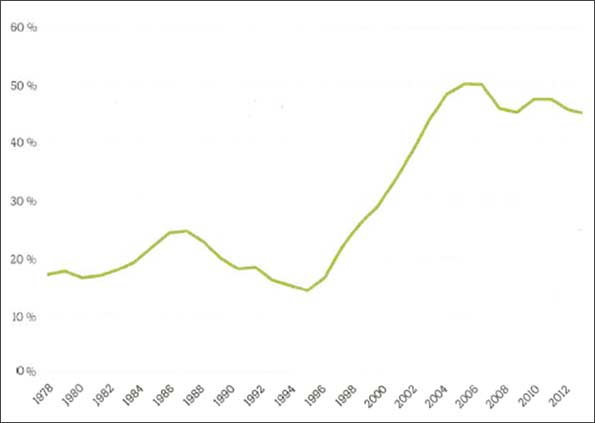

Our national statistics institute conducts regular wealth inquiries on the total wealth of French households. These studies show that the share of aggregate land value in homes value rose from 15% in 1996, to 50% in 2007, and slowly decreased then to 45% in 2013.

Fig 2. France – Share of land in aggregate real estate value

Source: J. Comby, computed from INSEE Annual wealth surveys

So, from these data, let’s compute how the prices of land and building components evolved between the 1996 low and 2007 peak, relatively to households revenue. The following table summarizes it all:

|

|

1996 |

2007 |

Price Increase |

|

Existing homes, average price – (current prices, €) (INSEE) |

77 100 |

192 800 |

+150% |

|

Average disposable income per household (current values, €) |

34 149 |

45 800 |

|

|

Ratio Home price / disposable income |

2.25 |

4.21 |

+86 % |

|

Land, % of home value |

15 |

50 |

|

|

Land, average value in existing homes (€) |

11 565 |

96 400 |

+ 733 % |

|

Land price appreciation, adjusted from household disposable income appreciation |

– |

– |

+ 520 % |

|

Building, average value in existing homes (€)

|

65 535 |

96 400 |

+ 47 % |

As has been seen in the Anglo-Saxon regulated markets, land appreciation overwhelms construction costs appreciation. Figures show clearly that the 1996-2007 real estate bubble is driven by land prices appreciation.

As a confirmation pattern, INSEE figures from its annual wealth studies show that the total value of built land plots went from 67% of GDP in 1998 (no figures for 1996) to 308% in 2007. So owning developable land in the end of the 90s provided returns that no other asset class could offer, despite creating absolutely no new added value for society. On the contrary, high home prices have been harmful to modest households, with 6% of people experiencing very bad housing conditions (obsolete and/or overcrowded units), 9% other having tough times financing their housing needs (1). And according to INSEE, there were 112 000 homeless people in 2012, a 44% increase from 2001 (2).

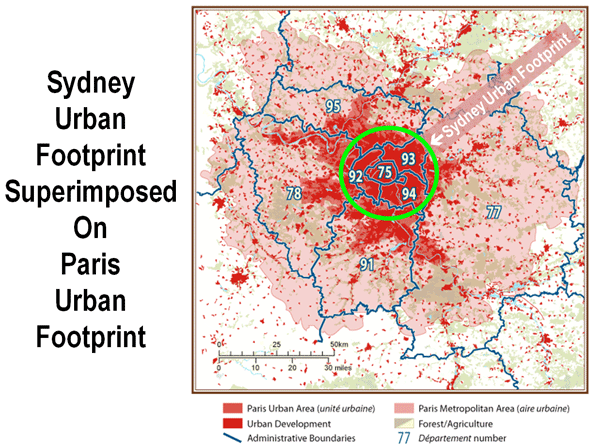

Since there is no physical shortage of land in France (most of the country is rather flat, and only 7% of land is developed), this suggests loudly to look at our land use regulations to understand how they fed the monster.

Our regulation of land belongs to the “prescriptive” family, according to Wendell Cox and Hugh Pavletich classification (3). It means that land is, by default, limited for natural or agricultural usage, and turning it into developable land must endure a long and politically complex zoning process. Worst of all, not only each city is zoned, but every local zoning has to comply, since the new millennium, with “territorial coherence schemes” which tend to cap the maximal amount of land available for development through years. Prescriptive regulations can be opposed to “responsive” ones, which can be seen in central parts of America and Canada. In a responsive regulatory frame, default status of land is let to the free choice of the owner, and only limitations for some collective purpose have to pass through a political process, and open a right for owners to be compensated for the loss of land value resulting of limitations. As Cox and Pavletich as well as the Brookings institution showed, places with prescriptive regulations experienced a much tougher bubble than responsive ones during the years of wild credit expansion. France is not different and the same phenomenon happened.

The idea of a bubble driven by strong regulatory constraints put on land meets a lot of resistance among several groups familiar in other countries: Local politicians, who get power from a population prone to NIMBY attitudes, and feeling richer through home value appreciation, are the first of them; most farmers, 70% of whom are renters, have an interest in preserving legal interdiction to turn plots at the fringe of cities into housing developments; and there are about 40,000 employees in public and private jobs who make a living from elaborating and implementing these regulations.

So we can see that in France, like other countries, the role of artificial restriction of land supply for new development can’t be dismissed. The costs and benefits of these regulations should be publicly questioned. Can their advocates still deny that that this price bubble is largely an unintended outcome of regulations. Nor can they acknowledge that this results in increasing levels of “housing poverty” and drives so much resources from more productive investments. Is this more desirable than “sprawl containment”, “farmland preservation” and other pretenses which provided justifications for these regulations in first place ?

Vincent Benard is senior economic analyst for the Turgot Insitute (www.turgot.org), a french classical liberal think tank. His principal interests are housing, land use and infrastructure policies, and the study of the unintended consequences of regulations. Since 2006, he authored one book and many articles about the French housing crisis. "

(FYI: The book : https://www.scribd.com/mobile/doc/80163334 – Free, PDF, in French)

———

Notes: (1) Figures from the annual report of the “Abbe Pierre” Foundation, dedicated to homelessness and poverty assistance www.fondation-abbe-pierre.fr/

(2) Source: “L’express”, November 2014 – http://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/le-nombre-de-sdf-en-france-a-explose-en-dix-ans_1623371.html

(3) See Annual Housing affordability report, by Cox and Pavletich, www.demographia.com

Photo by Benh LIEU SONG (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons