Ever since the Great Recession ripped through the economies of the Sunbelt, America’s coastal pundit class has been giddily predicting its demise. Strangled by high-energy prices, cooked by global warming, rejected by a new generation of urban-centric millennials, this vast southern region was doomed to become, in the words of the Atlantic, where the “American dream” has gone to die. If the doomsayers are right, Americans must be the ultimate masochists. After a brief hiatus, people seem to, once again, be streaming towards the expanse of warm-weather states extending from the southeastern seaboard to Phoenix.

Since 2010, according to an American Community Survey by demographer Wendell Cox, over one million people have moved to the Sunbelt, mostly from the Northeast and Midwest.

Any guesses for the states that have gained the most domestic migrants since 2010? The Sunbelt dominates the top three: Texas, Florida and Arizona. And who’s losing the most people? Generally the states dearest to the current ruling class: New York, Illinois, California and New Jersey. Some assert this reflects the loss of poorer, working class folks to these areas while the “smart” types continue to move to the big cities of Northeast and California. Yet, according to American Community Survey Data for 2007 to 2011, the biggest gainers of college graduates, according to Cox, have been Texas, Arizona and Floria; the biggest losers are in the Northeast (New York), the Midwest (Illinois and Michigan).

For the most part, notes demographer Cox, this is not a movement to Tombstone or Mayberry, although many small towns in the south are doing well, this is a movement to Sunbelt cities. Indeed, of the ten fastest growing big metros areas in America in 2012, nine were in the Sunbelt. These included not only the big four Texas cities—Austin, Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, San Antonio—but also Orlando, Raleigh, Phoenix, and Charlotte.

Perhaps the biggest sign of a Sunbelt turnaround is the resurgence of Phoenix, a region devastated by the housing bust and widely regarded by contemporary urbanists as the “least sustainable” of American cities. The recovery of Phoenix, appropriately named the Valley of the Sun, is strong evidence that even the most impacted Sunbelt regions are on the way back.

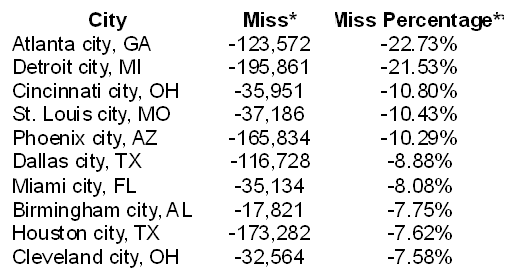

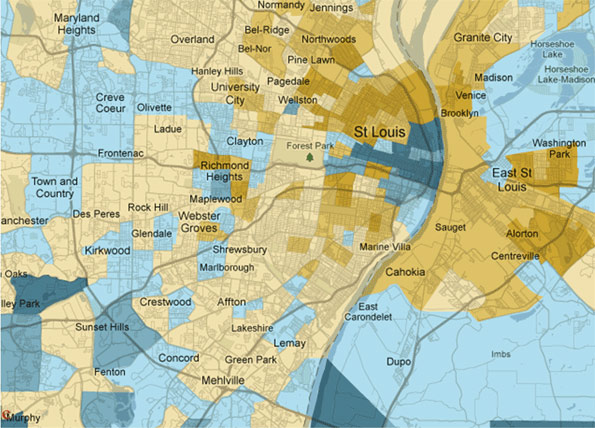

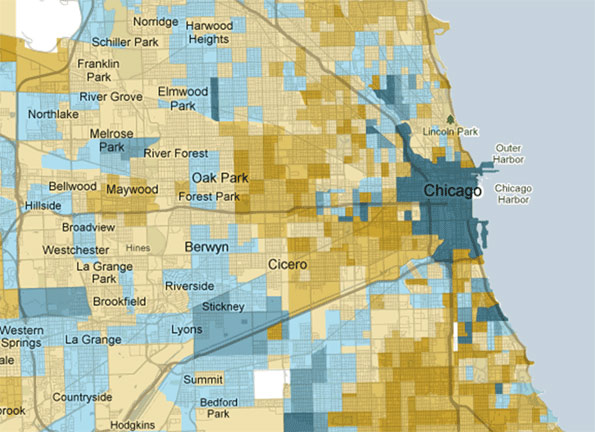

A look at the numbers on domestic migration undermines the claim that most Americans prefer, like the pundit class, to live in and near the dense Northeastern urban cores. People simply continue to vote with their feet. Since 2000, more than 300,000 people have moved to Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Charlotte; in contrast a net over two million left New York and 1.4 million have deserted the LA area while over 600,000 net departed Chicago and almost as many left the San Francisco Bay region. These trends were slowed, but not reversed, by the Great Recession.

The Sunbelt’s recovery seems likely to continue in the future. Immigrants, who account for a rising proportion of our population growth, are increasingly heading there. New York remains the immigrant leader, with the foreign-born population increasing by 600,000 since 2000 but second place Houston, a relative newcomer for immigrants, gained 400,000, more than Chicago and the Bay Area combined. The regions experiencing the highest rate of newcomers were largely in the south; Charlotte and Nashville saw their foreign-born populations double as immigrants increasingly beat a path to the Sunbelt cities.

The final demographic coup for the Sunbelt lies in its attraction for families. Eight of the eleven top fastest growing populations under 14, notes Cox, are found in the Sunbelt with New Orleans leading the pack. Generally speaking, roughly twenty percent or more of the population of Sunbelt metros are under 14, far above the levels seen in the rustbelt, the Left Coast, or in the Northeast.

This all suggests that the Sunbelt is cementing, not losing, its grip on America’s demographic future. By 2012 and 2017, according to a survey by the manufacturing company Pitney Bowes nine of the ten leading regions in terms of household growth will be in the Sunbelt.

If the population growth rates predicted by the US Conference of Mayors continue, Dallas-Ft. Worth will push Chicago out of third place among American metropolitan areas in 2043, with Houston passing the Windy City eight years later. Now seventh place Atlanta would move up to sixth place and Phoenix to 8th. Of America’s largest cities then, five would be located in the Sunbelt, and all are expected to grow much faster than New York, Los Angeles or the San Francisco area. Overall, the South would account for over half the growth in our major metropolitan areas in 2042, compared to barely 3.6 percent for the Northeast and 8.7 percent in the Midwest.

What drives the change? Not just the sun, but the economy, stupidos!

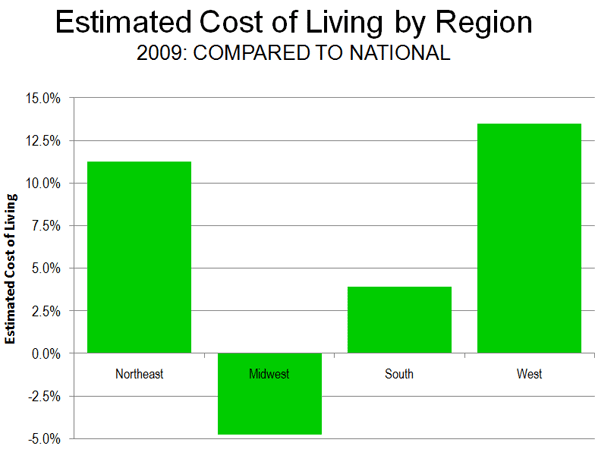

From the beginning of the Sunbelt ascendency, sunshine and warm weather have been important lures and this may even be more true in the near future. But the key forces driving people to the Sunbelt are largely economic—notably job creation, lower housing prices and lower costs relative to incomes.

Until the housing bust, states like Arizona, Nevada and Florida were typically among the leaders in creating new jobs but their performance fell off with the decline of construction. But other Sunbelt locales, notably Texas, Louisiana and Oklahoma have picked up much of the slack. This resurgence has been centered in Texas, which created nearly a million new jobs between 2007 and 2013. In contrast, arch-rival California has lost a half a million.

Many other Sunbelt states have yet to recover jobs lost from the recession, but most of their big metros have shown strong signs of recovery. Since 2007 five of the seven fastest growing jobs markets among the twenty largest cities were in Sunbelt states. Looking forward, recent estimates of job growth between 2013 and 2017, according to Forbes and Moody’s project employment to grow fastest in Arizona, followed by Texas. Also among the top ten are several states hit hard by the Recession, notably Florida, Georgia and Nevada. No Northeastern state appeared anywhere on the list; nor did California.

For all its shortcomings, including what some may consider the overuse of tax breaks and incentives, the much-dissed Sunbelt development model continues to reap some significant gains. The area’s history of lagging economically has long spurred Sunbelt economic developers to utilize a policy of light regulation, low taxes and lack of unions to lure businesses to their area. Sunbelt states—Texas, Florida, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Arizona—dominate the ranks of the most business friendly states in the union, notes Chief Executive magazine, findings they often cite when courting footloose businesses.

The clear economic capital of the Sunbelt is now Houston, with some stiff competition from Dallas-Ft. Worth. Houston, the energy capital, now ranks second only to New York in new office construction and is the overall number one for corporate expansions. There are fifty new office buildings going up in the city, including Exxon Mobil’s campus, the country’s second largest office complex under construction (after New York’s Freedom Tower). Chevron, once Standard Oil of California, has announced plans to construct a second tower for its downtown Houston campus while Occidental Petroleum, founded more than fifty years ago in Los Angeles, is moving its headquarters to Houston.

Houston’s ascendance epitomizes the shift in the geographic and economic center of the Sunbelt. The “original in the Xerox machine” for Sunbelt style growth, Los Angeles’ rise was powered by new industries like entertainment and aerospace and oil, ever expanding sprawl and a strong, tightly knit business elite. Pleasant weather and Hollywood glitz still inform the image of Los Angeles, but under a regime dominated by government employee unions, greens and developers of dense housing, it suffers unemployment almost four points higher than Houston . Nine million square feet of space is currently being built in Houston, compared to just over one million in Los Angeles-Orange which has more than twice the population. It is not in the rising Sunbelt but in places like Southern California, where jobs lag amidst high costs, that the American dream now seems most likely to die.

Movin’ on Up

In Houston particularly but throughout the Sunbelt, job growth critically is not tied to cheap labor, but to industries like energy which pay roughly $20,000 more than those in the information sector. According to EMSI, a company that models labor market data, energy has generated some 200,000 new jobs in Texas alone over the past decade. Although Houston is the primary beneficiary, the American energy boom is also sparking strong growth in other cities, notably Dallas-Ft. Worth, San Antonio, and Oklahoma City.

Once dependent on low-wage industries such as textiles and furniture, the energy boom is pacing a Sunbelt move towards generally better paying heavy manufacturing. Texas and Louisiana already lead the nation in large new projects, many of them in petrochemicals and other oil-related production. Of the biggest non-energy investments, three of the top four, according to the Ernst and Young Investment Monitor, are in Tennessee, Alabama and South Carolina, which are becoming the new heartland of American heavy manufacturing, notably in automobiles and steel. Since 2010, Birmingham, Houston, Nashville and Oklahoma city all have enjoyed double digit growth in high paying industrial jobs that used to be the near exclusive province of the Great Lakes, California and the Northeast.

The Sunbelt resurgence is important in part because it offers some hope to millions of Americans who may not have gone to Harvard or Stanford, but have work skills and ambition. The region’s growth in what might be called “middle skilled jobs” that pay $60,000 or above has been impressive.

It may come as a surprise to some, but the Sunbelt is also pulling ahead in high tech jobs. In a recent analysis of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) job growth for Forbes we found that out of out of the 52 largest regions, the four most rapid growers over the past decade were Austin, Raleigh, Houston and Nashville, with Jacksonville, Phoenix and Dallas also in the top fifteen. In contrast New York ranked #36th out of 52 and Los Angeles, a long-time tech superpower, now a mediocre #38.

In another example of how much things are changing, when college students in the South now graduate, noted a recent University of Alabama study, they do go to the “big city” but their top four choices outside the state are in the Sunbelt—Atlanta, Houston, Nashville, Tenn., and Dallas—and followed then by New York. The biggest net gains in people with BAs and higher are primarily in the sunbelt, led by Phoenix, Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Austin, Houston and San Antonio; the biggest losers, according to Cox’s calculations, have been New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and, surprisingly given its reputation, Boston.

These trends may become more pronounced as the current millennial generation starts settling down into family life. Housing costs could prove a decisive factor. In terms of the median multiple, median housing cost as share of median household income, Sunbelt cities tend to be about half as expensive as New York, Boston or Los Angeles, and one third of the Bay Area.

To be sure, many of the “best and brightest” will continue to flock to New York, the Bay Area or Los Angeles, but many more—particularly those without Ivy degrees or wealthy parents—may migrate to those places where their paycheck stretches the furthest. The Sunbelt, with its job growth, strong middle class wages and lows housing costs, is a good bet for the future.

What will the future bring?

Prosperity, Herodotus reminded us, “never abides long in one place.” Certainly the Sunbelt economy could lose its current momentum but fortunately, having been schooled by the housing bust, many Sunbelt communities are increasingly focused on improving their basic economy—jobs, income growth, and skills-based education. Tennessee and Louisiana, for example, have led the way on expanding working training, and some of most ambitious education reform is taking place in New Orleans and Houston.

Yet, there are many threats to continued growth, both internal and external. Given his penchant for executive orders and his close ties to wealthy green donors, President Obama could take steps—for example clamping down on fossil fuel development—that could reverse the steady growth along the Gulf Coast. Any draconian shift on climate change policies would be most detrimental to the energy sector Sunbelt states.

But President Obama will not be in office forever. In the long run, the biggest threat to the Sunbelt ascendency is internal. Some fear that as more easterners and Californians flock to the area, they will bring with them a taste for the very regulatory and tax policies that have stifled growth in the states they left behind . Most worryingly, so called “smart growth” regulations could drive housing costs up, as occurred in Florida and several other states in the last decade, and erode some of the Sunbelt’s competitive advantage.

Perhaps the most immediate threat comes from the angry, reactionary elements on the right, who tend to be more powerful in the sunbelt than elsewhere. These groups, sometimes including the Tea Party, have taken positions on issues like immigration and gay rights that local business leaders fear could deprive their regions of energetic and often entrepreneurial newcomers. Equally important, the right’s anti-tax orthodoxy, although perhaps not as devastating as the huge burdens placed on middle class individuals in the North and California, could delay critical outlays in transportation, parks and other essential infrastructure in regions that are growing rapidly. This is particularly true of education, a field in which most Sunbelt cities, while gaining ground, remain below the national average.

Whatever one thinks of the motivations of the green clerisy, there are clearly environmental measures, particularly in the Sunbelt’s western regions, that these cities need to enact to protect future growth. This includes reducing the amount of concrete that creates “heat islands,” expanding parks, and shifting to more drought resistant plants.

Fortunately, many leaders throughout the Sunbelt, particularly in its cities, are aware of these challenges, and are looking for ways to tackle them. This is driven not by the doomsday environmentalism common in California and Northeast, but grows instead out of a practical concern with stewarding critical resources and creating the right amenities to foster continued growth.

Combined with basics like lower housing costs and taxes, it’s a common optimism about the future that really underlies the resurgence now occurring from Phoenix to Tampa. The long-term shifts in American power and influence that have been underway since the 1950s have not been halted by the housing bust. Disdained by urban aesthetes, hated by much of the punditry, and largely ignored except for their failings in the media, the Sunbelt seems likely to enjoy the last laugh when it comes to shaping the American future.

This story originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Houston skyline photo by Bigstock.