Paul Krugman got it right. But it should not have taken a Nobel Laureate to note that the emperor’s nakedness with respect to the connection between the housing bubble and more restrictive land use regulation.

A just published piece by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, however, shows that much of the economics fraternity still does not “get it.” In Reasonable People Did Disagree: Optimism and Pessimism About the U.S. Housing Market Before the Crash, Kristopher S. Gerardi, Christopher L. Foote and Paul S. Willen conclude that it was reasonable for economists to have missed the bubble.

Misconstruing Las Vegas and Phoenix: They fault Krugman for making the bubble/land regulation connection by noting that the “places in the United States where the housing market most resembled a bubble were Phoenix and Las Vegas,” noting that both urban areas have “an abundance of surrounding land on which to accommodate new construction” (Note 1).

An abundance of land is of little use when it cannot be built upon. This is illustrated by Portland, Oregon, which is surrounded by such an “abundance of land.” Yet over a decade planning authorities have been content to preside over a 60 percent increase in house prices relative to incomes, while severely limiting the land that could have been used to maintain housing affordability. The impact is clearly illustrated by the 90 percent drop in unimproved land value that occurs virtually across the street at Portland’s urban growth boundary.

Building is largely impossible on the “abundance of land” surrounding Las Vegas and Phoenix. Las Vegas and Phoenix have virtual urban growth boundaries, formed by encircling federal and state lands. These are fairly tight boundaries, especially in view of the huge growth these areas have experienced. There are programs to auction off some of this land to developers and the price escalation during the bubble in the two metropolitan areas shows how a scarcity of land from government ownership produces the same higher prices as an urban growth boundary

Like Paul Krugman, banker Doug French got it right. In a late 2002 article for the Nevada Policy Research Institute, French noted the huge increases auction prices, characterized the federal government as hording its land and suggested that median house prices could reach $280,000 by the end of the decade. Actually, they reached $320,000 well before that (and then collapsed).

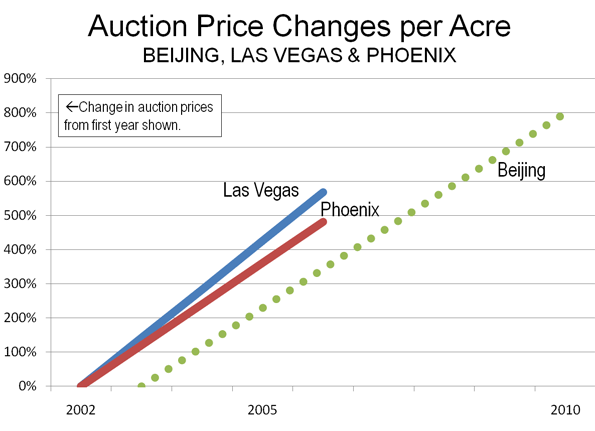

In Las Vegas, house prices escalated approximately 85% relative to incomes between 2002 and 2006. Coincidentally, over the same period, federal government land auctions prices for urban fringe land rose from a modest $50,000 per acre in 2001-2, to $229,000 in 2003-4 and $284,000 at the peak of the housing bubble (2005-6). Similarly, Phoenix house prices rose nearly as much as Las Vegas, while the rate of increase per acre in Phoenix land auctions rose nearly as much as in Las Vegas.

In both cases, prices per acre rose at approximately the same annual rate as in Beijing, which some consider to have the world’s largest housing bubble. According to Joseph Gyourko of Wharton, along with Jing Wu and Yongheng Deng Beijing prices rose 800 percent from 2003 to 2008 (Figure). This is true even thought we are not experiencing the epochal shift to big urban areas now going on in China.

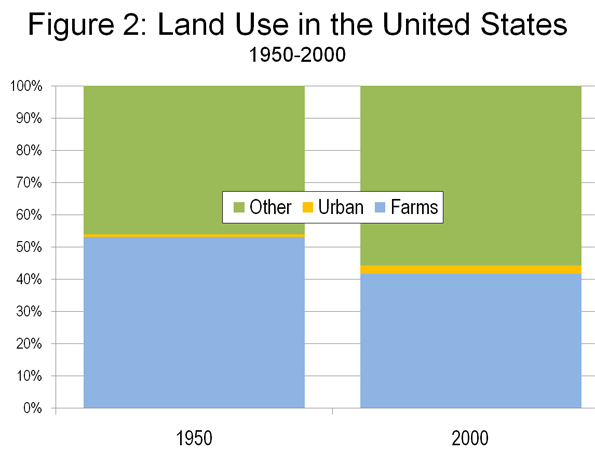

The Issue is Land Supply: The escalation of new house prices during the bubble occurred virtually all in non-construction costs such as the costs of land and any additional regulatory costs. It is not sufficient to look at a large supply of new housing (as the Boston Fed researchers do) and conclude that regulation has not taken its toll. The principal damage done by more restrictive land regulation comes from limiting the supply of land, which drives its price up and thereby the price of houses. In some places where there was substantial building, restrictive land use regulations also skewed the market strongly in favor of sellers. This dampening of supply in the face of demand drove land prices up hugely, even before the speculators descended to drive the prices even higher. Florida and interior California metropolitan areas (such as Sacramento and Riverside-San Bernardino) are examples of this.

Missing Obvious Signs: There are at least two reasons why much of the economics profession missed the bubble.

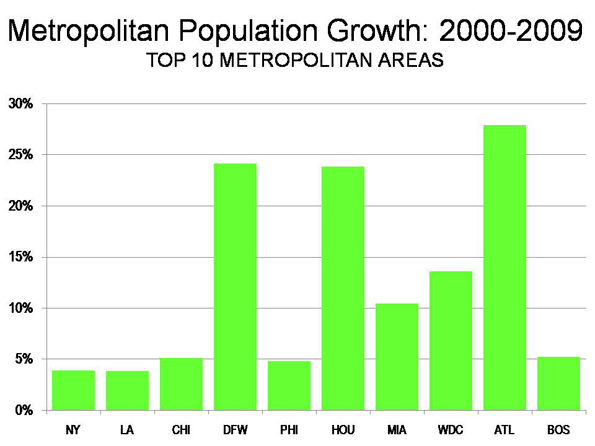

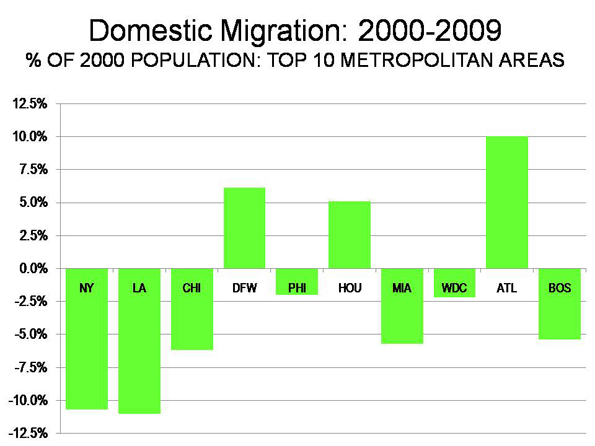

(1) Unlike Paul Krugman, many economists failed to look below the national data. As Krugman showed, there were huge variations in house price trends between the nation’s metropolitan areas. National averages mean little unless there is little variation. Yet most of the economists couldn’t be bothered to look below the national averages.

(2) Most economists failed to note the huge structural imbalances that had occurred in the distorted housing markets relative to historic norms. Since World War II, the Median Multiple, the median house price divided by the median household income, has been 3.0 or less in most US metropolitan markets. Between 1950 and 2000, the Median Multiple reached as high as 6.1 in a single metropolitan area among today’s 50 largest, in a single year (San Jose in 1990, see Note 2). In 2001, however, two metropolitan areas reached that level, a figure that rose to 9 in 2006 and 2007. The Median Multiple reached unprecedented and stratospheric levels in of 10 or more in Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and San Jose- all of which have very restrictive land use and have had relatively little building. This historical anomaly should have been a very large red flag.

In contrast, the Median Multiple remained at or below 3.0 in a number of high growth markets, such as Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston and other markets throughout the bubble.. Even with strong housing growth, prices remained affordable where there was less restrictive land use regulation.

Seeing the Signs: Krugman, for his part, takes a well deserved victory lap in a New York Times blog entitled “Wrong to be Right,” deferring to Yves Smith at nakedcapitalism.com who had this to say about the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston research:

It is truly astonishing to watch how determined the economics orthodoxy is to defend its inexcusable, economy-wrecking performance in the run up to the financial crisis. Most people who preside over disasters, say from a boating accident or the failure of a venture, spend considerable amounts of time in review of what happened and self-recrimination. Yet policy-making economists have not only seemed constitutionally unable to recognize that their programs resulted in widespread damage, but to add insult to injury, they insist that they really didn’t do anything wrong.

Maybe we should have known better: beware economists bearing the moment’s conventional wisdom.

——

Note 1: The authors cite work by Albert Saiz of Wharton to suggest an association between geographical constraints and house price increases in metropolitan areas. The Saiz constraint, however, looks at a potential development area 50 kilometers from the metropolitan center (7,850 square kilometers). This seems to be a far too large area to have a material price impact in most metropolitan areas. For example, in Portland, the strongly enforced urban growth boundary (which would have a similar theoretical impact on prices) was associated with virtually no increase in house prices until the developable land inside the boundary fell to less than 100 square kilometers (early 1990s). A far more remote geographical barrier, such as the foothills of Mount Hood, can have no meaningful impact in this environment.

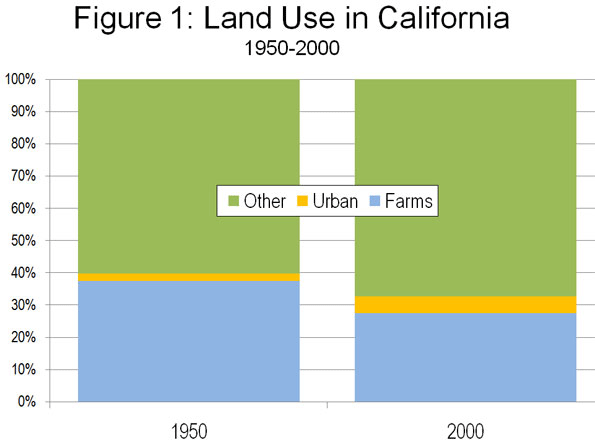

Note 2: William Fischel of Dartmouth has shown how the implementation of land use controls in California metropolitan areas coincided with the rise of house prices beyond historic national levels. As late as 1970, house prices in California were little different than in the rest of the nation.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photograph: $575,000 house in Los Angeles (2006), Photograph by author