As host of the G-20 summit, Pittsburgh briefly will sit in the global spotlight. With this article by longtime Pittsburgh resident and columnist Bill Steigerwald, New Geography opens a three part series looking at this intriguing metropolis from the point of view of planning, demography and economic performance.

Pittsburgh didn’t volunteer to host the G-20 Summit that is coming here next week to inflict so much civic pain and disruption.

It was entirely President Obama’s call. He apparently thought it would be a good idea to have the finance ministers and central bankers of the world’s top 20 economies hold one of their city-disrupting conferences in downtown Pittsburgh on Sept. 24-25.

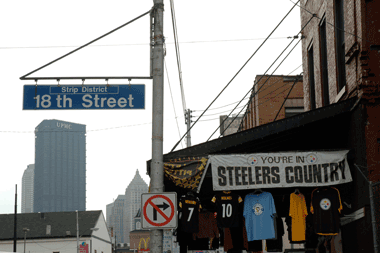

Perhaps Mr. Obama, who will chair the G-20, thought he was doing the financially strapped city of Pittsburgh a favor by sending 4,000 foreign bureaucrats and media folk here to spend their Euros and Yen on Steelers T-shirts and game jerseys.

Maybe he thought placing the G-20 meeting in Western Pennsylvania – a disproportionately Caucasian and socially conservative corner of America where his 2008 vote totals were disappointing – would pay him political dividends in the 2012 election.

In either case, the president was sadly mistaken.

Except for the local booster & tourism sector – who’d welcome a Category 8 hurricane to Pittsburgh as long as the international media covered it and said nice things about their no-longer smoky city – it’s safe to say everyone in this town who doesn’t work in the homeland security industry wishes they had never heard of the G-20.

As months of local media stories have made plain, the conference is not only going to be a huge public annoyance, it’s going to be a lose-lose situation for everyone – especially the city government.

Any economic benefits to the local GDP from the arrival of 4,000 visitors with fat expense accounts will be outweighed by the cost of protecting property from the tens of thousands of leftist protestors, angry anarchists and professional window-breakers who stalk G-20 meetings around the world.

To maximize security and minimize destruction, the Secret Service and local authorities will fortify most of the Golden Triangle, the photogenic downtown business district squeezed between the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers as they meet to create the Ohio River.

Barricades will be erected. Cars and mass transit will be diverted. Several major construction sites will be sealed off to deny protestors dangerous things to throw. Most downtown businesses probably will close. City schools and colleges will shut down.

The predicted cost to local public coffers for hiring, feeding and equipping additional police and paying overtime will be at least $20 million, most of which will be reimbursed by the federal government.

Whatever the final bill is, hosting the G-20 is an “honor” the city of Pittsburgh and its taxpayers didn’t need and can’t afford. The city is already bankrupt and in state receivership because of the generous pension deals it’s promised but won’t be able to pay for.

The city of Pittsburgh looks fabulous and robust when its skyline and riverbanks are shown on TV during Steelers home games. But it’s really the capital city of an economically stagnant, over-taxed, over-regulated, steadily depopulating metropolitan region that has been horribly governed for 60 years.

The private-public power-brokers who’ve run the city have wasted billions on a never-ending series of destructive urban renewal projects, redevelopment boondoggles and wasteful mass-transit projects.

Almost nothing has been built in downtown Pittsburgh or on its riverbanks in the last 20 years without being handed millions in public subsidies – whether it was PNC Financial Service’s almost completed downtown skyscraper, a gorgeous Lazarus department store that went bust in the ‘90s or the shiny new homes for the Pirates, Steelers and (soon) the Penguins.

If curious G-20 attendees have time to stroll around the city’s abandoned downtown streets on Thursday and Friday, they will have no trouble finding evidence of City Hall’s current crop of fiascoes-in-the making.

Right in front of fancy Fifth Avenue Place, for example, is a deep trench where busy Stanwix Street should be.

It’s not where a Scud missile hit during the first Gulf war. It’s the construction zone of one end of the local mass transit system’s infamous “Tunnel to Nowhere.”

The 1.2-mile light-rail extension goes from Gateway Center downtown under the Allegheny River to the North Shore, where its other end has been tearing asunder the wasteland of former parking lots between the subsidized new homes of the Steelers and Pirates for several years.

The twin light-rail tunnel – cleverly built under a river in the “City of Bridges” so as to maximize the cost and provide unions and construction companies with six or seven years of high-paid make-work – will allegedly carry 4.2 million riders a year in the distant transit future.

That impressive but fraudulent projection comes out to about 11,000 “riders” a day – which actually represents only 5,500 human commuters making a (two-ride) round trip commute. A large proportion of those annual riders, by the way, will be baseball or football fans.

All that socially correct “mass transit” will end up costing at least $650 million, with federal and state taxpayers picking up about 97 percent of the tab. Except for yours truly and the conservatives on the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review’s editorial page, virtually no one in local politics or the media questioned or challenged the lunacy of building the transit tunnel.

Another wasteland in the middle of downtown that G-20-goers might visit is the flattened construction site that used to be Market Square.

Once upon a time, before City Hall planners began demolishing and rebuilding huge chunks of downtown in the 1950s; it was what urbanists are supposed to encourage: an actual square with markets.

Then, in the 1960s, the city took it over and transformed it into a poorly designed, commerce-free urban park with trees, grass and heavy city bus traffic. The public space delighted crowds of lunching office workers at midday but the rest of the time it was a lawless playpen for about 100 homeless people, drunks and drug pushers.

Today the area around Market Square, last refurbished in the 1990s, hardly has a live store or restaurant left standing. It is waiting to be turned into its next reincarnation – a $5 million European-style piazza with no vehicles piercing its heart and no low walls and green spaces for social misfits to reside.

On one edge of battered Market Square is Fifth Avenue, which has been tortured constantly by City Hall for about 25 years.

In the early 1980s, its street surface was torn up for several years so the city’s rinky-dink light-rail subway could be built beneath it. Not long after that, Fifth Avenue was rendered virtually impassable to shoppers for a couple years while the city slowly redid its sidewalks and curbs.

Then, in the late 1990s, Fifth was targeted by City Hall for a preposterously stupid and destructive redevelopment scheme.

The crude 1960s-style renewal project would have misused eminent domain power to clear-cut Fifth Avenue and Forbes Avenue, wipe out nearly 100 businesses and build what amounted to an outdoor suburban mall anchored by a Nordstrom store.

Fortunately, that plan was miraculously stopped by an alliance of preservationists and property rights defenders. But is it any wonder that after a quarter century of torture by city planners Fifth Avenue became “dilapidated” and in need of serious redevelopment?

As G-20 attendees will learn if they bother to walk a few moments from their hotels, the nightmare on Fifth Avenue continues. Its northern end is currently being torn down, fixed up, blocked to pedestrians or under construction.

PNC Financial is putting the final touches on its new 23-story, $178 million headquarters – which received $48 million in state and local subsidies and wiped out half a block of retail storefronts. Meanwhile, up the street, the lovely stone tomb the city erected in the late 1990s for Lazarus has been all but given away to a local developer who’s converted it into a pricy condo and office space that still has 32 of its 65 units to sell.

Whenever the national media rediscover the glories of Pittsburgh’s clear skies and affordable livability, which they seem to do every four years, they never stick around long enough to note the failings of its governments and politicians.

Taxes on property and people and businesses are too high. The city schools are absurdly expensive and ineffective. The roads and 1950s parkways are old, narrow and crumbling. Public services are often poor or costly. Unions and Democrats wield the sort of uncontested political power that’s never good for a municipality.

Yes, it is still true, as the national media and local booster sector never tire of repeating, that the “City of Champions” and its suburbs are a great place in which to live, raise a family, grow old and die peacefully.

With its famous three rivers and hills and bridges and skyscrapers and hillside homes and urban neighborhoods and spectacular views and historic downtown buildings, Pittsburgh is rich in natural and man-made charm.

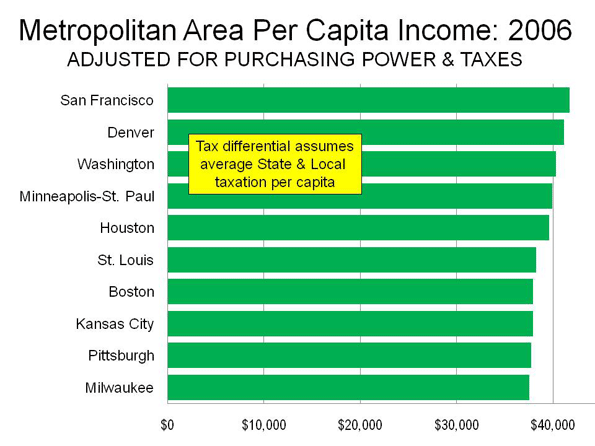

Toss in a cost of living 17 percent below the national average and low crime rates, lots of good affordable housing, major-league super-teams like the Steelers and Penguins, great museums like the Carnegie and top universities like Carnegie Mellon and Pitt – Pittsburgh does deserve to be ranked highly on those meaningless most-livable city lists.

It’s also true – as some in the national media latched on to earlier this year – that compared with many other parts of the country, Pittsburgh has not suffered greatly in the current recession.

Pittsburgh has an unemployment figure lower than the national average, a very low home-foreclosure rate and stable-to-slightly-rising housing prices.

But Pittsburgh’s good fortune was not, as out-of-town media claimed, because its wise leaders had figured out how to dodge a severe economic downturn. Or because – as President Obama has been led to believe – the region’s post-industrial “eds and meds” service economy is particularly healthy or even resilient.

Pittsburgh’s relatively impressive economic statistics are pretty much the 30-year norm for Pittsburgh – in times of national booms or busts. They probably won’t change for the better unless the spectacularly rich Marcellus shale natural gas deposits lying underneath western Pennsylvania are exploited, which may not happen for decades or ever happen at all.

There’s one thing about Pittsburgh’s future that is a near certainty: It’s going to have fewer residents next year than it has today.

Since the mid-1990s, Pittsburgh has had more deaths than births each year. Between 2000 and 2006, in fact, it had 21,045 more deaths than births, earning it the distinction of being the largest metropolitan area where deaths outnumber births.

That negative ratio wouldn’t be so bad if immigrants from anywhere else were flocking to Pittsburgh. But they aren’t. Metro Pittsburgh has the lowest percentage of foreign-born residents of any major city – 3 percent – compared to 12.5 percent nationally.

Pittsburgh has only about 7,000 immigrants from Latin America – second to the 7,800 who hail from India. Only 16,000 international immigrants arrived in metro Pittsburgh between 2000 and 2006, dead last among the 25 largest cities.

Post-industrial decline, out-migration, too many older people, more deaths than births, too few immigrants from Mexico and Georgia – they’ve all contributed to Pittsburgh’s incredible six-decade population decline.

In 1950, Pittsburgh was the country’s 12th biggest city. It had 676,806 citizens in a metropolitan area of about 2.5 million.

Today the metro population, ranked 22nd, is down to 2.35 million and Pittsburgh’s surviving population of 310,000 live in the country’s 59th biggest city – right behind Aurora, Colo., a growing municipality that will never have to worry about getting stuck with hosting a G-20 summit.

Photos by Bill Steigerwald.

Bill Steigerwald, a free-lance libertarian writer who recently retired from daily newspaper journalism, loves his native Pittsburgh but hates the political and corporate power brokers who’ve been damaging the city for 60 years. His columns are archived at the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review and his 2000 article for Reason magazine on the city’s abuse of eminent domain powers is here.