When it comes to the future, Detroit and San Francisco act as poles in the continuum of American consciousness. Detroit is dead and will continue dying. San Francisco is the region sipping heartily from the fountain of youth. Such trajectories, according to experts, will go on indefinitely.

Harvard economist Ed Glaeser has a grim outlook for the Rust Belt. “[P]eople and firms are leaving Buffalo for the Sunbelt because the Sunbelt is a warmer, more pleasant, and more productive area to live,” he writes in City Journal.

Glaeser echoes this sentiment in a recent interview with International Business Times, saying “[s]mart people want to be around other smart people”, and the Rust Belt has a long slog ahead given that “post-industrial city migration is dominated by people moving to warmer climes”.

But is this true? Is there a “brain drain” from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt and Coasts? In a word: no. But Rust Belt leaders have bought this narrative hook line and sinker, and the subsequent hand-wringing has led to wasteful public investment.

“Michigan’s cities must retain and attract more people, including young knowledge workers, to its cities by making them attractive, vibrant, and diverse places,” reads a 2003 memo from the National Governor’s Association about Michigan’s “Cool Cities” campaign.

But the campaign struggled. “Government can’t mandate cool,” reflected Karen Gagnon, the former Cool Cities director. “As soon as government says something is cool, it’s not.”

What’s worse, “cooling you city” with talent attraction expenditures can exacerbate economic disparities on the ground. Cities, like Chicago, are increasingly becoming bifurcated cities based on faulty assumptions that “trickle down urbanism” works. That said, the challenge of the day—for not only Rust Belt cities, but all cities—is not “brain drain”, but “brain waste”. Those cities who can best rebuild middle class communities tied to emerging markets will be the future of investment, like they were in the past.

Through Rust-Colored Glasses

When a people fall from grace, the sentiment of decline tends to stick. The Rust Belt’s demise is cemented. Meanwhile, the future is elsewhere. Like toward the sun. For instance, from 2000 to 2010, the Sun Belt metros of Houston, Dallas, Atlanta, Riverside, Las Vegas, Miami, Orlando, and Phoenix experienced the largest population growth. The biggest losers? It’s a “who’s who” of Rust Belt metros, led by Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Buffalo.

America is a country governed by growth: big cars, big belt buckles, big houses, and big populations. Shrinkage is weakness. It is a sign of place failure. The problem here is that population growth is an ineffective, broad-brush measure when trying to understand regional underlying dynamics. A new study by Jessie Poon and Wei Yin in the journal Geography Compass called “Human Capital: A Comparison of Rustbelt and Sunbelt Cities” details exactly that.

In it, the authors compare human capital levels between the Sunbelt metros in California (including San Francisco and L.A.), Nevada, New Mexico, and Arizona with Rust Belt metros in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and upstate New York. When it comes to share of population with a college degree, the authors find that the Rust Belt is experiencing a brain gain equal to their Sun Belt peers from 1980 to 2010. Poon and Wei also found that skill ratios of immigrants is higher in the Rust Belt than Sunbelt. The authors note that despite population decline, the Rust Belt continues “to be important sites of human capital accumulation”.

The study coincides with recent work out of the Center for Population Dynamics that shows Greater Cleveland’s number of 25- to 34-year olds with a bachelor’s or higher increased by 23% from 2006 to 2012, as well as Pittsburgh economist Chris Briem’s work that shows the metros of Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Cleveland rank 1st,, 6th, 7th in the country respectively when it comes to the number of young adults in the labor force with a graduate or professional degree.

Beyond human capital, the Rust Belt continues to produce and export wealth at a massive pace. The “Chi-Pitts” mega-region, which mirrors the Rust Belt boundaries with the addition of Minneapolis, generates $2.3 billion in economic output, second only to the “Bos-Wash” mega-region that makes up the Northeast Corridor.

Also, using IRS migration data from the 2009-2010 period, a team of researchers led by Michal Migurski showed that Los Angeles County, New York County, and Cook County sent the most people and money to the rest of the United States. Detroit’s Wayne County was fourth. Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County was 9th, one spot ahead of San Francisco County. Speaking to Esquire, which published the work in a visual called “Where Does the Money Go”, Migurski explains the findings:

"We realized that if you look at the biggest ‘losers,’ essentially what you’re looking at are the biggest cities in the U.S.," Migurski says. One of those losers: New York County, which lost $1,306,548,000 and 15,100 people. "But does that actually mean New York is a big loser?" Migurski asks. "One of our ideas was that, you’re not a loser if you’re losing money. You’re an exporter." The sort of exporter, he says, that boosts the rest of the U.S. economy. Traditional Sun Belt retirement areas comprise the gainers; areas like South Florida and Southern California in particular, create what Migurski calls "money sinks."

Still, the notion of “loser” for Wayne and Cuyahoga County sticks, despite evidence to the contrary. But why? Why the constant “poor post-industrial people” sentiment, if not a low-grade captivation that comes with “ruin porn” rubbernecking?

Well, if an ideal exists—you know, the experts beckon: be the “new” city, the “hot” city, the “creative” city—then a study in contrasts is necessary. The Rust Belt, with its connotations of smoke stacks and demographic decline, fits the bill.

“[Richard] Florida suggests that Rustbelt cities’ high concentration of less creative blue-collar workers also produces unhappy residents,”Poon and Wei conclude in their Rust Belt/Sun Belt study. “We suggest that such a doom and gloom picture of urban and regional development for the uncool industrial Rustbelt needs to be tempered with a trend of brain gain that is growing across cities in the region.”

But for this tempering to happen a clearer understanding of the importance of accumulating human capital needs to be ascertained. More exactly: Is it to put your city to work, or to “live-work-play”?

Build it and they will…what?

In his 1921 work Economy and Society, social scientist Max Weber details a city’s raison d’etre. Cities can be producer cities, wherein importance is derived from industries that demand national and international trade. Think Detroit and cars. Additionally, cities are consumer cities, in which growth is tied to how much is spent consuming goods and services in the local economy. Think eating, drinking, and buying houses.

The cities that are the most economically robust have wealth generated from global production, which in turn enables local consumption. San Francisco’s tech economy drives it real estate market and artisanal toast scene. That is, if the question was “What came first, the farm-to-table chicken or the egghead?” The answer is “the egghead”, hands down.

But this logic—i.e., in order to go to a restaurant, you need a job, and your job prospects are tied to the viability of your region’s global industries—is often turned on its head in economic development. Here, the goal is growth, no matter the rhyme or reason.

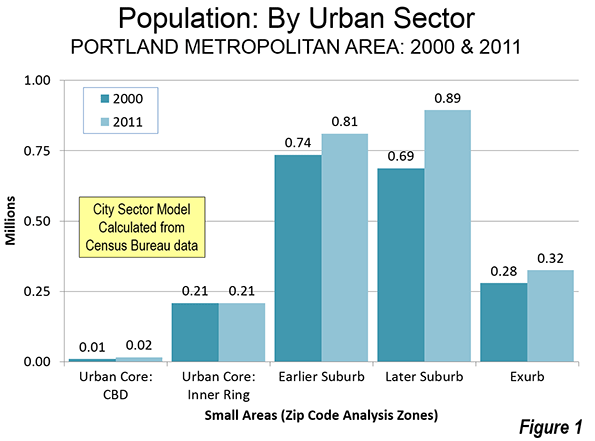

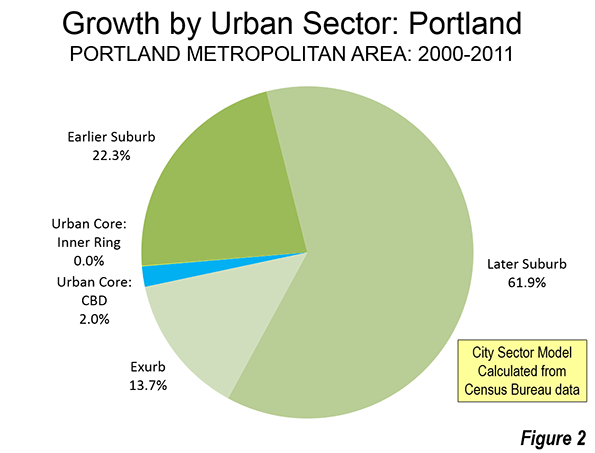

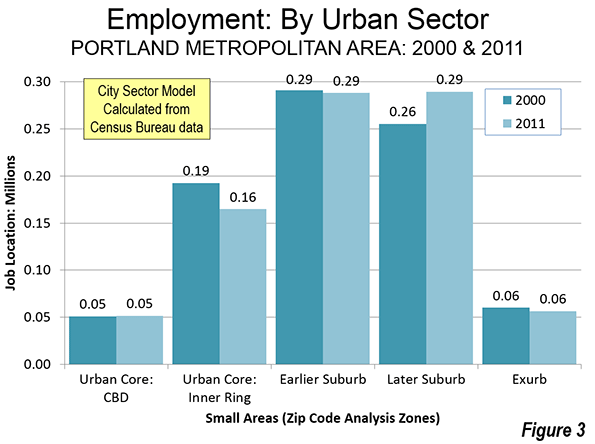

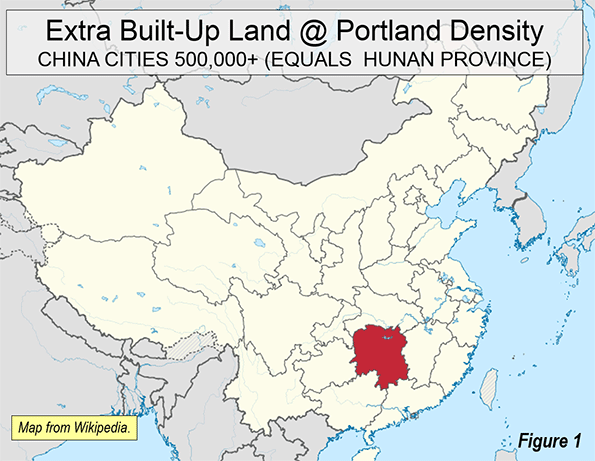

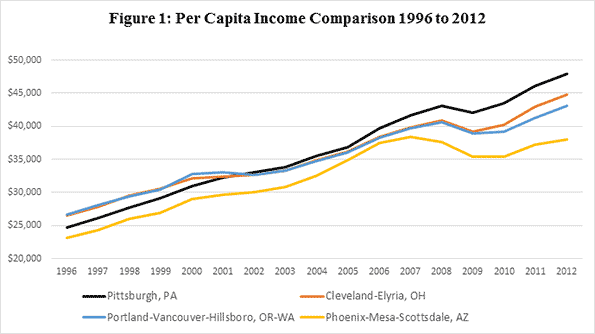

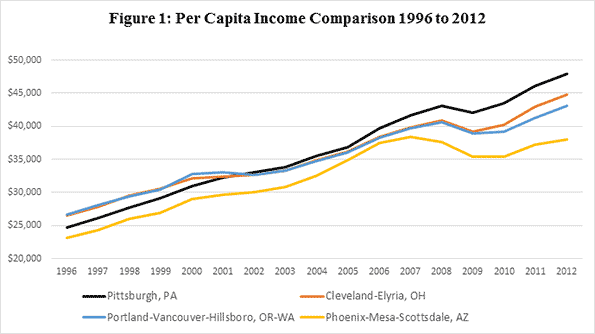

“Like in many Sun Belt cities,” writes a Seattle Times columnist and Sun Belt expat, “Phoenix’s economic plan devolved into merely adding people, no matter the enormous long-term costs”. The columnist goes on to note that while the population has boomed, the city lags on most measures, such as per capita income (see Figure 1 below).

Moreover, the Phoenixes of the world exist partly because of retired Baby Boomers and the disposable income that comes with it. The Sun Belt feeds off the legacy of production in the Northeast and Midwest. Other cities, like Portland, are fed by a not dissimilar dynamic. But it’s not the retired who come, rather the pre-retired.

“The Portland metro area’s young college-educated white men are slackers when it comes to logging hours on the job,” lead’s a piece in the Oregonian about a study conducted last year, “and that’s one reason people here collectively earn $2.8 billion less a year than the national average.” Figure 1 demonstrates Portland’s sluggish income gains compared to Rust Belt peers Pittsburgh and Cleveland.

Similarly, in a paper circulated by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, the author analyzed the top 86 “brain gain” metros in the nation to determine whether or not a region’s increase in human capital was paying off in terms of per capita income, labor force participation, poverty rate, and unemployment. The author found Portland was one of twelve metros that experienced zero economic outcomes. Pittsburgh scored 4 for 4. The authors suggest that talent attraction and retention—when untethered to production capacity—“may be largely inefficient, a kind of traditional economic development ‘buffalo hunting’”.

Portland is perhaps America’s consummate lifestyle city. No doubt, the city has experienced a significant brain gain over the last decade. Portland is a talent attraction model. But it is not a talent producing or refining model. Rather, Portland is producing a scene that is run by the consumption of the scene’s aesthetic. Writes one young worker who left:

“I can’t stay too long because I know if I stayed a day too long in Portland, I’d suddenly be happy to embrace the slow pace of the city and stop working… I’d end up getting sleeping real late every day, drink some coffee, maybe write some poetry on my porch (or not), and then find a part time job selling cigars like I had in college.”

The lesson is that accumulating talent is not enough. There has to be something for the talent to do, or a context that fosters “doing”. It is also a warning for cities investing in the lifestyle game. Spending on creative class amenities ensures nothing. Creating a field of dreams won’t pay the bills. But it will run up the tab.

The Ugly City Beautiful

In 1998, the Chicago Sun-Times ran a piece called “Building the City Beautiful”. “The mayor of the city of Chicago, Richard M. Daley, is a big admirer of Martha Stewart,” it begins, before describing Daley’s plans to begin the "Martha Stewart-izing" of Chicago. The article goes on to quote a University of Illinois at Chicago professor who said Chicago is turning from a producer city to a consumer city. "The producer city was the industrial city — the smoke and the noise and the industrial jobs,” noted the professor. “The consumer city is the city of Starbucks, boutiques and so forth.”

The professor was only partly right. By the 1990s, Chicago was indeed becoming brainier. But its emerging knowledge economy was an outgrowth of its “big shouldered” manufacturing base. Columbia University professor Saskia Sassen recently noted that pundits overlook this when examining the city’s transformation, with the bias being that “Chicago had to overcome its agro-industrial past, [and] that its economic history put it at a disadvantage”. Notes Sassen:

[I]n my research I found that its past was not a disadvantage. In fact, it was one key source of its competitive advantage. The particular specialized corporate services that had to be developed to handle the needs of its agro-industrial regional economy gave Chicago a key component of its current specialized advantage in the global economy.

Similar economic transformations from legacy cost to legacy asset are found throughout the whole of the Rust Belt. Pittsburgh, for instance, no longer provides the muscle for steel making, but it does act as the “brain center” for the world’s steel frame. How this came about is detailed in the article “Pittsburgh’s evolving steel legacy and the steel technology cluster”.

With the arrival of the new economy also came “new economy” tastes. Sassen noted that when she arrived in to study in Chicago in the 90s she was greeted by “old lofts transformed into beautiful restaurants catering to a whole new type of high-income worker—hip, excited, alive.”

In other words, local consumption patterns began setting up around the emergent worker demand. Going was the Italian Beef and arriving was pickled beets. This demand also impacted housing, with the attraction to urban living setting the stage for gentrification. This, in a nutshell, is the dynamic driving the transformation of urban neighborhoods nationwide: a new economy demands new workers which in turn demand a new kind of lifestyle. The problem, though, is that leaders have the causality backward, or that creating a new lifestyle will incur new worker supply and then poof: new industries. But as we see with Portland, it is not that easy. The industrial DNA and social history of your city matters more than the cosmetics atop the topography.

Still, from a policy and strategy standpoint, it is easier just to make your city “cool”. And that’s exactly what Chicago has been doing at a significant pace. In a recent piece entitled “Well-healed in the Windy City”, author Aaron Renn details Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s policy of using tax-increment financing (TIF) to create geographic “winners” and “losers” across Chicagoland. “The true purpose of Chicago’s TIF districts—which now take in about $500 million per year,” writes Renn, “appears to be tending to high-end residents, businesses, and tourists, while insulating them from the poorer segments of the city.”

The strategy was spelled out explicitly by Mayor Emanuel during a recent ribbon cutting for a bike path in Chicago’s Loop. Said Emanuel: “I expect not only to take all of their [Seattle and Portland’s] bikers but I also want all the jobs that come with this, all the economic growth that comes with this, all the opportunities of the future that come with this.”

Notwithstanding the faulty logic in the strategy—e.g., if Portland lacks the jobs for its residents, how can it supply jobs for Chicagoans—the real problem is the costs associated with such bifurcated investment. In West and South Chicago, the byproducts of the City Beautiful approach are downright ugly. But they are not unexpected. They are the long-documented economic and social effects of concentrated poverty and segregation. Continues Renn:

Safety levels in Chicago can no longer be plotted on a single bell-shaped curve for the entire city. Today, that curve is split into two—one distribution for the wealthy neighborhoods and one for the poor ones. A lack of resources is part of the problem: the police department is understaffed… While the city budget is tight, failing to increase police strength during a murder epidemic is a profound statement of civic priorities.

Urban priorities flow from a perception of what is at stake. For long, the push for human capital accumulation has pitted city versus city amidst the backdrop of an urban popularity contest in which the “winner” is assured nothing outside of popularity. But victory in the vanity game is fleeting. The young and the restless are exactly that, and many people who come to New York or San Francisco, or for that matter Portland, leave as they get older and seek out affordable places to raise a family. What remains on the ground is the reality of brain waste. Without the prioritization of equitable, integrated middle-class neighborhoods a city’s progress will be always be disparate, if not illusory. Talent attraction is but part of a redevelopment process. So is talent refinement for those arriving and talent production for those in place. After all, neighborhoods are factories of human capital. Building people, not places, is what a successful city is all about.

But to know this is to “know thyself”. The Rust Belt has been dying for some time now, so say the experts. The region has absorbed the projections, and given that desperate times call for desperate measures investment has been wasted. “[Creative class theory] is bad because it distracts from what’s important,” says Sean Stafford, author of Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngstown.

Regaining focus entails removing the rust-colored glasses. Rust Belt leaders will see there are assets to work with, not to mention feel the freedom that comes with no longer being a study in contrast for those touting a future that really isn’t.

Richey Piiparinen is Senior Research Associate at the Center for Population Dynamics at the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University. The Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State University’s Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs aims to help partner organizations competitively position the region for economic and community development. It will do so through the lens of migration, applied demography, and culture.

Lead photo courtesy of bctz Cleveland