Tri-Met, the operator of Portland’s (Oregon) bus and light rail system has been in the news lately, and in less than auspicious ways. For decades, the Portland area’s media – as well as much of the national press – has been filled with stories about the national model that Tri-Met has created, especially with its five light rail lines.

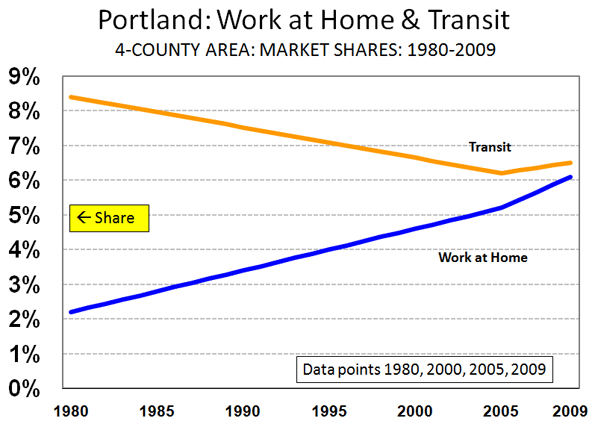

The reality is less impressive. After spending an extra $5 billion over the past quarter century, public transit’s share of work trip travel in Portland is less than it was before. Moreover, the Portland has now become the 38th of the major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) in which more people work at home (such as telecommuting) than ride transit to work.

Tri-Met’s more recent notoriety also reveals some serious concerns about financial management . Auditors recently finished their annual report, and it indicates that that Tri-Met has run up some rather large bills that it may be hard-pressed to pay.

Unfunded Pension Liabilities: Unfunded liabilities on Tri-met’s employee pension funds have grown to more than $260 million. This deficit has developed because Tri-Met can not meet its obligation to pay into the pension funds on a current basis. Indeed, at the rate Tri-Met paid the pension funds for fiscal year 2010 (ended June 30), they would be more than eight years delinquent. Overall, the pension funds are nearly 50 percent under funded.

Other Post-Employee Benefits: “Other Post-Employee Benefits” (OPEB), made up principally of retiree health care, pose a much bigger problem. As of the end of the fiscal year, the unfunded liability for these benefits was $817 million, up $185 million in just one year. Underfunding is an even greater problem. The retiree benefits are 100 percent under funded. Tri-Met has simply put no money aside for these benefits. Tri-Met has achieved world class status in underfunding its OPEB. The Los Angeles MTA, which carries nearly five times as much travel volume as Tri-Met had unfunded OPEB liabilities of only $730 million (still a huge figure) in 2009, which is the last data available.

When challenged on the huge unfunded liability and its growth, Tri-Met General Manager Neil McFarlane responded to KATU-TV: “That’s adding apples, oranges and grapefruits together to get a completely unreasonable number.” One wonders what kind of complications the chief executive office of a publicly traded Fortune 500 company would face for similarly dismissing inconvenient data in its annual report (whether from the Securities and Exchange Commission, the board of directors or the stockholders).

The auditor, Moss-Adams, LLP appended a standard opinion, to the effect that “… the financial statements … present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the District as of June 30, 2010…” At another point the auditors note their obligation to perform the audit to “obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement.” As far as McFarlane is concerned, there may be some disagreement on whether the financial statements are “free of material misstatement, “given that they include a “completely unreasonable number.”

A Train of Debt: Other Tri-Met woes come from its frequent bonds issues, which to date have been approved with little oppostion. The present bonded indebtedness is more than $250 million. The agency is asking the electorate for approval of another $125 million in bonds at the November 2 election. The Oregonian, which has been a friend to nearly everything Tri-Met has done, is recommending a “no” vote on the bonds, pointing out that they would not be necessary if Tri-Met had saved sufficiently for vehicle replacement. Further, Tri-Met is searching hard for more money to fund a deficit in its proposed light rail line to suburban Milwaukie in Clackamas County, which seems a questionable project given the agency’s inability to keep fares under control and maintain service levels.

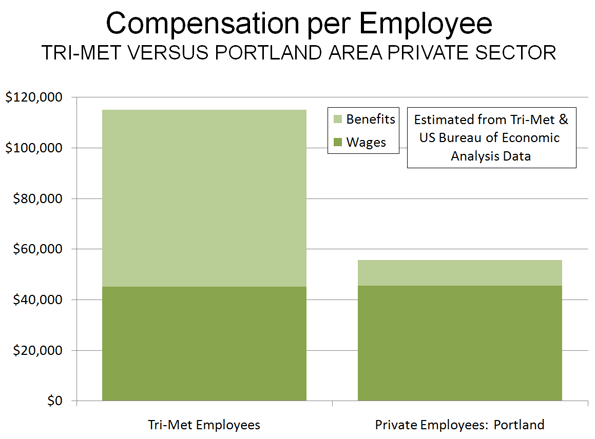

Bloated Benefits: John Charles, President of the Cascade Policy Institute raised eyebrows when he noted that Tri-Met’s employee benefits expense is by far the highest in the nation. Charles looked at 20 large transit agencies and found that employee benefits were equal to 152 percent of the wage bill, approaching double that of the next highest, San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit District and Washington’s Metropolitan Transit Authority. With their above 80 percent employer-paid benefits ratios, albeit lower than Tri-Met’s 152 percent, these agencies have nothing to be proud of. In the private sector, employer-paid benefits tend to be less than 25 percent of wages. Tri-Met’s 152 percent is six times that.

Bloated Compensation: With a benefits ratio of 152 percent, payroll expense per employee is a stratospheric $115,000 annually (assumes the 2008 staffing ratio, later data not identified). In contrast, the average private sector employee in the Portland metropolitan area is compensated at approximately $55,000 annually, which includes wages and a 22 percent extra for benefits (Figure 1).

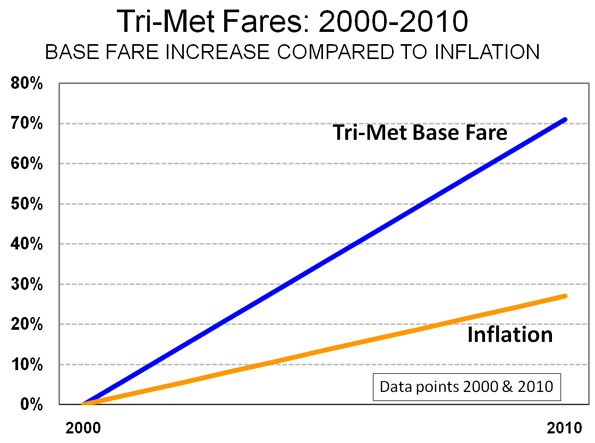

Employees Ahead of Customers: Tri-Met implemented a fare increase in September and reduced bus service by 5.8 percent and light rail service by 3.5 percent. In the last 10 years, the basic bus fare has risen 71 percent, well above the 27 percent inflation rate (Figure 2). The fare increases and service cuts are imposing substantial hardship on many Tri-Met riders, who have limited incomes and no access to cars. The above inflationary fare increases represent a financial management failure of fundamental proportions.

Yet while it was raising fares, Tri-Met also increased union employee compensation by three percent and covered increases of 7.5 percent to 22.5 percent on two employee health care programs. Tri-Met has admitted that these increases were not legal obligations (could this be a gift of public funds?). The cost of the non-obligatory wage increase was more than double the amount Tri-Met expects to raise from the September fare increase. Some discontinued service could have been financed with the rest of the wage increase money and the non-obligatory health care premium increases.

Rising Costs: The question for Portland and Tri-Met remains whether this financial house of cards is sustainable. Operating and capital costs have, not surprisingly, skyrocketed. In fiscal year 2010, it is estimated that costs per passenger mile rose to more than $1.35. This is a full 40 percent above the the national transit average. This is more than five times the per passenger mile – full cost of cars and sport utility vehicles including all user costs and the portion of road expenditures (principally local streets) paid for by taxes – of less than $0.25.

Fiscal Imprudence: Past and Future: There is some too-little, too-late good news for riders. Tri-Met has told the union that it will not cover health care benefits increases in 2011, nor will there be another non-obligatory wage increase. In its editorial opposing approval of the bond issue The Oregonian spoke of “past fiscal imprudence.” In appears that the mecca of transit is becoming less a role model and more a cautionary tale.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photo: Mount Hood in exurban Portland (by author)

Recently (February), I examined tax assessment records for all parcels in Portland’s Washington County that abut the urban growth boundary to see if value differences exist. The properties had to be 5 or more acres and be undeveloped. Research was conducted based upon Internet information in February 2010. Property along 25 miles of the urban growth boundary from Cedar Hills to Hillsboro to southwest Beaverton was included in the analysis.

Recently (February), I examined tax assessment records for all parcels in Portland’s Washington County that abut the urban growth boundary to see if value differences exist. The properties had to be 5 or more acres and be undeveloped. Research was conducted based upon Internet information in February 2010. Property along 25 miles of the urban growth boundary from Cedar Hills to Hillsboro to southwest Beaverton was included in the analysis.