For many locals, Silicon Valley surrendered to the tyranny of development when it lost its last major fruit orchard in 1996. Olson’s family cherry orchards, a 100-year player in the valley’s agricultural history, shut down its main operations, and Deborah Olson mournfully told a local reporter then, “We’re down to 15 acres at this point.” There is a happy ending. With community support, the Olson family continues to sell its famous cherries at its fruit stand in Sunnyvale, Calif.

Ultimately, Silicon Valley’s history is predicated on a continual progression from industrial to post-industrial. Adding to the chaotic ferment and success, multiple sectors co-exist at different stages of maturity at any given moment.

Before its industrial period, the region was an agrarian economy. At the height of the farming boom in the 1920s and 1930s, over 100,000 acres of orchards blanketed the valley. In 2006, farming continued to thrive across the broader San Francisco Bay Area in resilient specialty pockets, which included organic farms, gourmet cheese producers, and wine vineyards. Stett Holbrook reported that roughly 20,000 acres of agriculture remained, most of it clustered in southern Santa Clara County around Morgan Hill, Gilroy, and the Coyote Valley. New technologies and tools modernized local farming practices, so that what exists today is a far cry from efforts a century ago. Now the region produces 1.3 million tons of food annually, according to the Greenbelt Alliance.

By the 1920s, as farms began to industrialize, a big push occurred next in manufacturing, namely in automobile production, shipbuilding, and food canning.

The local auto industry shows a constant rise and fall. In the 1920s, Oakland became known as the “Detroit of the West” with factories operated by General Motors, Chrysler, Fageol Motor Company, and Durant Motors. All closed over the next 30 years or so, as the auto industry first consolidated to the Great Lakes and later shifted overseas, as well as the southeast.

The Bay Area saw a resurgent interest in car manufacturing in the 1980s when Toyota – a complete unknown in the earlier era – teamed up with GM to open the New United Motor Manufacturing Inc. (NUMMI) plant in Fremont, Calif. Now 25 years later, Toyota announced that all NUMMI operations will close by March in response to recent economic pressures.

NUMMI’s closing is emblematic of the nature of employment change that accompanies broader industrial change. Currently, 4,700 people work at the auto factory, and another 50,000 people work for suppliers and other businesses that depend on NUMMI’s ongoing operations.

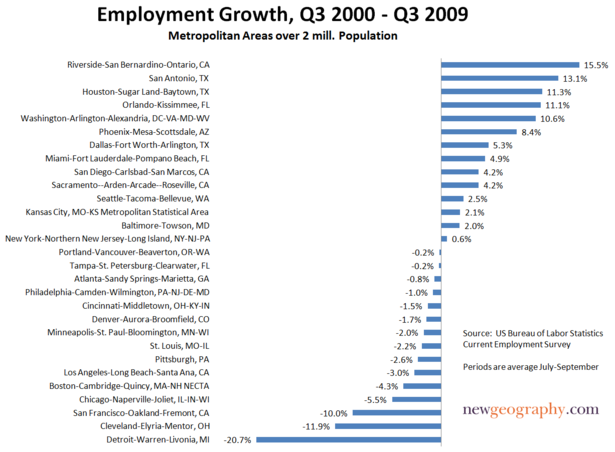

Local and state leaders are concerned about the larger regional impact. Over the last 12 months, the East Bay has lost 4,400 manufacturing jobs, a decline of 5 percent in that industry, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In comparison, Silicon Valley lost 13,800 manufacturing jobs, an 8 percent decline. Bruce Kern, executive director of the East Bay Economic Development Alliance, told the press, “You have the jobs from suppliers and other vendors that provide goods and services to NUMMI.” Most of these workers are stranded with skills only suitable for the industrial Silicon Valley, so Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger announced that California state will focus on retraining them, as well as finding alternative uses for the roughly 5 million-square-foot NUMMI factory.

On the other side of the Bay, Tesla Motors today is making the transition from a cottage to a production industry, and it has also shifted gears in its manufacturing plans. The highly subsidized company had originally planned to build an electric car factory in San Jose earlier this year, but Tesla is now close to a deal to build an electric car factory at the site of a former N.A.S.A. manufacturing plant in Downey, Calif., a blue-collar city south of Los Angeles.

Shipbuilding offers a counter example. While efforts have largely vanished from the area, a few notable examples have survived in new form. For instance, Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, Calif., developed a new medical system for its shipyard workers in WWII that eventually became the basis for Kaiser Permanente, a highly successful modern health care organization. Here is an early example of a company converting its business model from hardware to service.

But the high point of the industrial era dates from the 1950s when U.S. defense contracts spurred the area’s growth, building aerospace and other military equipment largely through Lockheed Martin. Then, as magnetic core memories were replaced by semiconductor memory chips in computers, semiconductor and chip manufacturing soared in the 1960s and 1970s, dominating the Valley with industrial fervor.

By the late 1970s, however, Silicon Valley had lost its lead in memory chips, thanks to several revolutionary measurement tools from Hewlett-Packard’s Japanese partnership. The Japanese soon took over the memory chip business, going from less than 10% to over 80% of worldwide chips in six short years. Today, the memory chip market is an $18 billion worldwide market with virtually no U.S. manufacturers. In order to thrive against this fierce competition, Silicon Valley companies had to re-invent themselves, such as Intel’s adoption of the microcomputer chipsets now known as Pentium.

Other areas of the information technology (IT) industry have also undergone reinvention. Charles House, in The HP Phenomenon, points out that Hewlett-Packard has re-invented itself six times in seven decades. Apple has also done so in spectacular fashion, first with computers, then with music, and now smartphones. Since 1976, Apple has gradually evolved from a computer hardware manufacturer into a consumer electronics company. The company originally handled most manufacturing locally, but by 1992, Apple had closed its plant in Fremont, Calif., and moved all operations out to Colorado, Ireland, and East Asia. For a time, Apple elevated its role in the industrial process, noting on its products: “Designed in California, assembled in China.”

Apple’s decision reflects a larger trend in Silicon Valley to shift more to post-industrialized work, marked by higher value technology services within a knowledge economy.

Another example is VIA Technologies, a chip manufacturer founded in Fremont in 1987, which moved its headquarters in 1992 to Taiwan. Richard Brown, vice president of international marketing at VIA, explained, “The main reason was that we saw that Taiwan would replace Silicon Valley as the global hub for PC, notebook, and motherboard design and manufacturing.” He added, “It enabled us to get closer with key manufacturing partners in Taiwan.”

Now expanded as a fabless semiconductor design company, VIA has kept a strong presence in Silicon Valley these last two decades. About 250 employees work locally. Brown said, “We conduct advanced R&D work on chipsets and graphics in our Fremont office, and we also have extensive customer support and sales operations covering the U.S. and Latin America.”

Beyond IT, where is new industrial growth occurring in the Bay Area?

One economic indicator is demand in office and warehouse space. The U.S. industrial vacancy rate hit a decade high last quarter, marking the eighth consecutive quarter of increasing vacancy, according to real estate services firm Colliers International. Nationally, warehouses under construction declined to the lowest number Colliers has on record, and both bulk warehouse space and tech/R&D space showed larger decreases in rental rates than prior years.

The Silicon Valley market was the third largest contributor to the national drop after Chicago and the Los Angeles basin. Jeff Fredericks, senior managing partner out of Colliers’ San Jose office, has observed that no sector has been left unscathed locally.

He noted, “Very little manufacturing or industrial space has been built in Silicon Valley in the last 10 years, and that trend is likely to continue.” Fredericks believes, however, that some light manufacturing will continue to exist within the region, either to support local technology companies or simply because the business owners choose to live here.

He added, “Certainly, green tech is a market favorite right now, but that really only forms a small percentage of Silicon Valley’s total market. Nonetheless, it is a sector that is experiencing better growth than others.”

Richard Ogawa has seen a similar regional boom in the clean tech industry. As an intellectual property attorney with Townsend and Townsend and Crew LLP, Ogawa currently advises several clean tech start-up companies that are funded by Khosla Ventures, among others. Several companies, such as Stion Corporation and Solaria Corporation, have built pilot production lines. Part of the clean tech growth can be attributed to stricter state regulations, which push for greater reliance on renewable energy sources. He said, “It’s very geographic-centric.”

Ogawa has also seen a rise in small-scale manufacturing in other industries. For example, within the local apparel business, Levi Strauss & Co. shuttered its last operating factory in 2002, which had been operating since 1906. Many locals were discouraged to see the longtime factory close. Today, retail manufacturers like Golden Bear Sportswear and Timbuk2 actively operate in San Francisco, but of course with far smaller workforces.

Personally, Ogawa is a wonderful embodiment of industrial and post-industrial Silicon Valley. As a third generation Northern Californian, whose father owned a farm in the Central Valley, Ogawa specializes in post-industrial work. His clients in semiconductors, software, networking, and lately clean tech mix industrial and post-industrial work, either shifting manufacturing abroad or undertaking light production locally.

Reflecting on the changes he has witnessed over time, Ogawa said, “I’m not aware of any industry that’s left the area, at least in my lifetime.” In Silicon Valley, most industries simply take on new form as part of the constant evolution from industrial to post-industrial.

Tamara Carleton is a doctoral student at Stanford University, studying innovation culture and technology visions. She is also a Fellow of the Foundation for Enterprise Development and the Bay Area Science and Innovation Consortium.