Despite some hype and a few regional exceptions, the construction of office towers and suburban office parks has not made a significant resurgence in the current recovery. After a century in which office space expanded nationally with every uptick in the economy, we may have reached something close to “peak office” in most markets.

The amount of new office space in development is extraordinarily low by historical standards, outside of a handful of markets. Back in the mid-1980s, according to the commercial real-estate research firm CoStar, upward of 200 million square feet of office space was built annually. After dropping precipitously in the early 1990s, construction rose again to 200 million square feet a year in the early 2000s before dropping well under 150 million square feet in 2006, and lower after that. This year, in what is purported to be the middle of an economic recovery, we will add barely 30 million square feet,according to Reis Inc.

Even with this paltry construction, vacancy rates nationwide have barely moved, hovering around 17%. This is nowhere near low enough to justify much more construction in the vast majority of markets, where office rents remain well below 2007 levels.

Indeed, the trend in real estate remains to convert office spaces to other uses,particularly residential. Large-scale office construction is happening in just a handful of markets; New York and Houston are the only ones with 10 million square feet being built, with smaller amounts in the works in Boston, Washington, Dallas-Ft. Worth and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Most of the current anemic growth is happening outside downtown areas. Silicon Valley, which is essentially a sprawling suburb, currently has about as much construction as San Francisco. In Houston, another big metro area with robust job growth, there is a new 47-story high-rise being developed downtown, but much of the action is taking place on the periphery, notably in the Energy Corridor. ExxonMobil’s massive new campus, at 3 million square feet, ranks with One World Trade Center in Manhattan as the nation’s largest new office projects.

Through the third quarter this year, the amount of new office space under construction in suburban areas was roughly double the amount being built in central business districts, by CoStar’s count. Furthermore, only 7.1 million square feet of office space was absorbed downtown in the first nine months of 2013, compared to 51.5 million in suburban areas, CoStar says. But overall there is still 100 million square feet less space being used today than in 2007, and at current absorption rates, it could take six or seven years just to get back to where we were before the recession.

The Weak Economy

The key question here is not the geography of office space but why so little is being built. As long as economic growth is modest, don’t expect much change in the skyline in most downtowns, or suburbs. Job growth has been mediocre at best, and much of that has been in the low-wage and part-time category. McJobs and part-time workers do not generally fill office towers.

The dirty little secret of this recovery is that labor participation rates are at the lowest level since 1978. Underemployment is rife, at around 18% to 20%, and much of that likely includes large numbers of people who used to work in offices.

This is true even in New York City, where the rate of “office-using employment” has been dropping since the late 1960s and even in the recovery, has yet to rebound to the levels of 2000.

Changing Use of Space

Just as we have gotten used to more fuel-efficient cars, companies now utilize space more efficiently than before, largely through information technology. This is a trend many companies plan to accelerate. In the past, for example, your average mid-level executive had his own secretary; now it’s more common to have perhaps one aide for several managers. Historically office developers assumed that each worker would require 250 square feet of space; by the end of the decade this could drop to 100 to 125 square feet.

Even the most notoriously bureaucratic of professions, law, is scaling back. A recent Cushman and Wakefield survey found that most firms — many already downsizing — were working to reduce their office footprint per attorney from 800 to 500 square feet. Almost two out of five expect to use “hoteling,” or the sharing of offices among attorneys, something very rare a decade ago.

At the same time, some of the sectors that are the best bets for expansion, such as information technology and media, are increasingly seeking out unconventional office space. Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s drive to upzone large parts of Midtown Manhattan to create ever-taller towers works operates on the assumption that new users will be much like the old ones. But some experts, such as New York-based architect Robert Stern, suggest that ultra high-rise development does not appeal to either creative businesses and tourists, while preserving older districts, with already developed buildings, does.

Self-Employment and Home-Based Businesses

Perhaps the biggest long-term threat lies in the shift from corporate to self-employment. From 2001 to 2012, the number of self-employed workers grew by 14%, according to a recent study by Economic Modeling Specialists. This is occurring not only in the metro areas that suffered the worst during the recession, such as Phoenix, Los Angeles and Riverside-San Bernardino, but also in the healthiest economies such as Houston and Seattle.

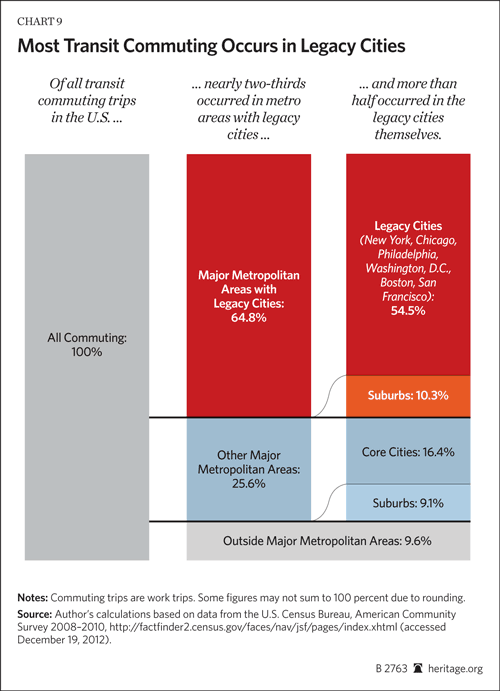

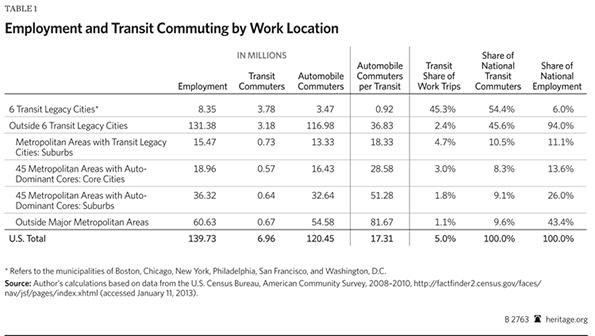

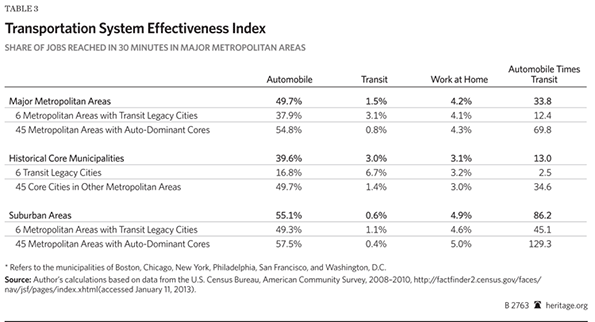

Some of these now self-employed workers may end up in small offices, but many don’t leave home at all. Working at home is growing far faster than commuting by either car or transit, and in most U.S. metro areas, far exceeds those who get to work by public conveyance, most often to downtown areas. Over the past decade the number of U.S. telecommuters expanded 41% to some 1.7 million, almost double the much-ballyhooed increase of 900,000 transit riders.

Are We Blowing Another Bubble?

In some specialized, fast-growing markets, new office construction may well be justified. Raleigh is seeing some new construction in its small downtown, as are hot job markets such as Austin and oil-rich Midland, Texas, where a proposed 53-story office tower would be the tallest building between Dallas and Los Angeles.

But in New York, plans for massive new office tower construction seem to contradict an unemployment rate considerably above the national average. Financial services, the primary driver of the Manhattan market, is showing signs of economic distress, with firms moving middle-management jobs to more affordable places such as Richmond, Va.; Pittsburgh; St. Louis; and Jacksonville, Fla.

Perhaps even more worrisome, less than half of the space in new buildings in Manhattan is preleased, compared to over 70% in both Houston and Boston, and a remarkable 92% in San Jose/Silicon Valley. This reflects an apparent dearth of large employers in New York who could conceivably afford and fill ultra-expensive office space in the coming years, a recent article in Crain’s New York points out. Tech companies might be expected to help fill the gap, but we have to remember that after the last boomlet Silicon Alley suffered asteep contraction; it has since recovered, but could be hit hard again if the current bubble pops.

San Francisco, the other current darling of office developers, is even more dependent on the current dot-com boom. The IPOs of Frisco-based firms such as Twitter appear to suggest the prospect of a whole new generation of office occupants. By one account, there is as much as 12 million square feet of new office space in the pipeline in the city, enough to satisfy historical demand for the next 16 years.

Yet past experience shows many of these companies will likely dissolve or merge in the next few years. They may be fewer in numbers and longer established than last time around, as some local boosters eagerly suggest, but most are still unprofitable and many may never be truly viable. Following the 2000 dot-com crash, San Francisco office occupancy dropped roughly 10 million square feet, while tech employment crashed from a high of 34,000 in 2000 to barely 18,000 four years later. As one real-estate executive put it at the time, “The office-space market here ”reminds me of the Road Runner cartoon where the Coyote runs into the wall.”

Observers also point out that more traditional businesses, such as banks, continue to ship jobs elsewhere, in large part due to extraordinarily high costs. The fact that pre-leasing for SF’s new office buildings is barely 33% should add to the caution.

None of this suggests there are not some good opportunities for new construction, but the office building’s role as a key indicator of the strength of the U.S. economy has faded. In great cities, rather than a ballyhooed era of new office skyscrapers we will see more conversions and the construction of residential high-rises, as well as medical buildings. The secular trend is for the dispersion of business service employment to smaller markets, and into people’s homes. The glory days of the American office tower are over, and not likely to return soon, given technological trends and a persistently tepid economy.

This story originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Photo by Mark Lyon — Full Floor For Rent.