Technology is reshaping our economic geography, but there’s disagreement as to how. Much of the media and pundits like Richard Florida assert that the tech revolution is bound to be centralized in the dense, often “hip” places where “smart” people cluster. Some, like Slate’s David Talbot, even fear the new tech wave may erode whatever soul is left to increasingly family free, neo-gilded age San Francisco.

Such claims have been bolstered by the tech boom of the past few years — especially the explosion of social media firms in places like Manhattan and San Francisco. Yet longer-term trends in tech employment suggest such favored media memes will ultimately prove well off the mark. Indeed, according to an analysis by the Praxis Strategy Group, the fastest growth over the past decade in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics-related) employment has taken place not in the most fashionable cities but smaller, less dense metropolitan areas.

From 2001 to 2012, STEM employment actually was essentially flat in the San Francisco and Boston regions and declined 12.6% in San Jose. The country’s three largest mega regions — Chicago, New York and Los Angeles — all lost tech jobs over the past decade. In contrast, double-digit rate expansions of tech employment have occurred in lower-density metro areas such as Austin, Texas; Raleigh, N.C.; Columbus, Ohio; Houston and Salt Lake City. Indeed, among the larger established tech regions, the only real winners have been Seattle, with its diversified and heavily suburbanized economy, and greater Washington, D.C., the parasitical beneficiary of an ever-expanding federal power, where the number of STEM jobs grew 21% from 2001 to 2012, better than any other of the 51 largest U.S. metropolitan statistical areas over that period.

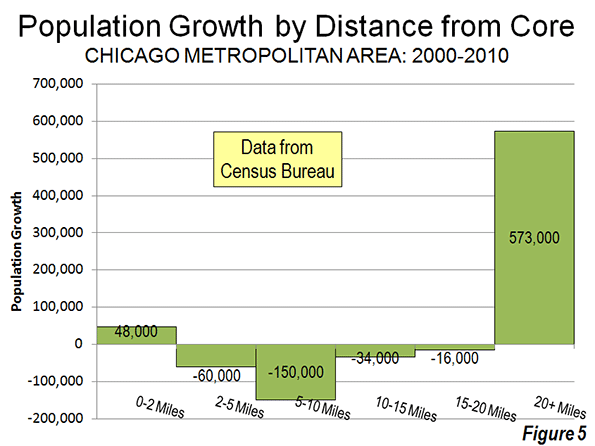

The question is whether the last two to three years, during which places like San Francisco, New York and Boston have enjoyed stronger STEM growth than their peripheries, represents a paradigm shift or is just a cyclical phenomenon. As with tech in general, the long-term trends are not so city-centric; over the past decade, the core counties nationwide overall have lost about 1.1% of their tech jobs while more peripheral areas have experienced a gain of 3.5%.

Today’s urban tech boom looks a lot like a rerun of the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. In that period media-savvy dot-com startups proliferated in such places as South of Market in San Francisco and the Silicon Alley in lower Manhattan. At their height, these firms and their founders were as likely to be covered in the fashion and lifestyle sections as on the business pages.

Yet by the early 2000s, many of these dot-com darlings had merged, been acquired or simply gone out of business. Anchored largely on hype, they fell victim to flawed business models, and rapid industry consolidation. In San Francisco, for example, tech employment crashed from a high of 34,000 in 2000 to barely 18,000 four years later. Silicon Alley suffered a similar downward trajectory, losing 15,000 of its 50,000 information jobs in the first five years of the decade.

The peaking social media boom, marked by the weak performance of Facebook’s IPO last year, suggest another bust at the end of the “hype cycle.” Urban darlings such as San Francisco’s Zynga and Chicago’s Groupon have floundered in spectacular fashion. More are likely to join them.

These firms may have generated buzz, but they have done not so well at the mundane task of making money. One problem may be that the most avid users of social media are largely young people from the “screwed” generation who lack much in the way of spending power — a clear turnoff to advertisers. Now , with venture capital flows declining overall, cooler heads in the Valley are shifting bets to more business-oriented engineering and research-intensive fields more grounded in marketplace realities.

And what about the future of the Valley — still home to virtually all the Bay Area’s top tech firms? Its glory days as a job generator and economic exemplar seem to have passed. Between 1970 and 1990 the number of people employed in tech in the Valley more than doubled to 268,000, and then burgeoned to over 540,000 in the 1990s. At the peak of the last tech boom in 2001, the unemployment rate in Santa Clara County was a tiny 3%; the Silicon Valley Manufacturing Group confidently predicted there would be another 200,000 jobs by 2010.

However, at what may be the peak of the current boom, the number of tech jobs in the Valley remains down from a decade ago and unemployment is over 7.7%, just around the national average. In reality, social media was never going to reverse the downward trajectory in the rate of job growth. Old-line companies like Hewlett-Packard or Intel, with over 50,000 employees in the U.S. alone, were capable of creating a broad range of opportunities for workers; in contrast, the social media big three of Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter together have less than 6,500 employees.

As the social media industry matures and consolidates, employment is likely to continue shifting to less expensive, business-friendly areas. The Bay Area, where the overall cost of living is 68% higher than the national average and housing is the most expensive in the nation, may continue to attract and retain only the highest-end, best-paid workers. But for the most part they will follow the path of established tech firms such as Apple, Intel, Adobe, eBay and IBM to lower-cost places like Austin, Columbus and Salt Lake City. A similar phenomena also can be seen in other urban-centered industries, such as entertainment and finance where virtually all employment growth is in places like St. Louis, Des Moines and Phoenix, even as the largest centers, New York, Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco have suffered significant job losses.

Demographic forces may further accelerate these trends. The critical fuel for tech growth, educated labor, is now expanding faster in places like Columbus, Austin, Raleigh, Dallas and Houston than in Boston, San Jose and San Francisco. The old centers may still enjoy a lead in brains, but other places are catching up rapidly.

Companies may also discover that with many millennials starting to hit their 30s, some may seek to leave their apartments to buy houses and start families. In California new local regulations essentially ban the construction of new single-family homes in some of the state’s biggest metro areas, pricing this option out of reach for all but a few, and forcing a key demographic group to seek residence elsewhere.

Under these conditions, Silicon Valley will be forced to rely increasingly on inertia and mustering of financial resources than innovation. As a result, the nation’s tech map will continue to expand from the Bay Area, Boston, Seattle and Southern California to emerging metropolitan areas in North Carolina, Texas, Utah, Colorado and the Pacific Northwest. In the future parts of Florida, Phoenix, and even Great Plains cities like Sioux Falls and Fargo could also achieve some critical mass.

Ultimately, one of the main dynamics of the information age — that even sophisticated tasks can be done from anywhere — works against the dominion of single hegemonic industry centers like Wall Street, Hollywood and Silicon Valley. The tech sector is particularly vulnerable to declustering, due in large part thanks to the freedom from geography created by technologies of its own making. Silicon Valley may continue to reap riches from the periodic technology gold rush , but in the longer term, tech growth will continue its long-term dispersion to ever more parts of the country.

| STEM Occupations in the Nation’s 51 Largest Metropolitan Areas | |||||

| MSA Name | 2001 – 2012 Growth | 2005 – 2012 Growth | 2010 – 2012 Growth | 2012 Location Quotient | LQ Change, 2001 – 2012 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 21.1% | 12.7% | 3.7% | 2.19 | 10.6% |

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | 18.6% | -1.4% | 2.2% | 0.57 | 1.8% |

| San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX | 18.3% | 17.2% | 4.5% | 0.83 | 1.2% |

| Baltimore-Towson, MD | 17.9% | 11.4% | 3.9% | 1.37 | 15.1% |

| Raleigh-Cary, NC | 17.9% | 14.6% | 6.2% | 1.53 | 0.0% |

| Las Vegas-Paradise, NV | 17.2% | -2.6% | 0.8% | 0.52 | 4.0% |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 16.3% | 18.1% | 7.4% | 1.16 | 4.5% |

| Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX | 15.7% | 17.2% | 6.6% | 1.20 | -2.4% |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 15.4% | 22.2% | 6.7% | 1.86 | 8.1% |

| Jacksonville, FL | 13.0% | 6.5% | 2.4% | 0.87 | 8.7% |

| Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, TX | 12.2% | 17.2% | 9.1% | 1.82 | -8.5% |

| San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA | 11.3% | 8.0% | 2.1% | 1.38 | 6.2% |

| Columbus, OH | 10.4% | 12.8% | 4.7% | 1.27 | 7.6% |

| Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL | 9.4% | -1.1% | 0.8% | 0.84 | -3.4% |

| Indianapolis-Carmel, IN | 6.9% | 6.5% | 2.7% | 1.04 | 2.0% |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | 6.7% | 3.5% | 2.4% | 0.77 | -1.3% |

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA | 6.4% | 3.5% | 0.4% | 1.33 | 2.3% |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 5.5% | 9.6% | 6.4% | 0.89 | -1.1% |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 5.3% | 10.3% | 4.9% | 1.07 | 5.9% |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | 4.8% | 2.3% | 0.5% | 1.10 | 3.8% |

| Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC-SC | 4.3% | 8.2% | 5.7% | 0.99 | -3.9% |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | 4.0% | 5.8% | 4.6% | 1.12 | 4.7% |

| Richmond, VA | 3.8% | 4.4% | 3.4% | 0.99 | 0.0% |

| Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN | 3.7% | 5.5% | 6.8% | 1.02 | 4.1% |

| Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY | 3.2% | 6.4% | 3.6% | 0.90 | 4.7% |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 3.1% | 11.4% | 5.5% | 1.19 | -5.6% |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA | 2.5% | 15.0% | 9.9% | 1.63 | 5.8% |

| Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale, AZ | 2.3% | 3.5% | 3.9% | 1.05 | -6.3% |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 2.2% | 6.7% | 5.9% | 1.31 | 1.6% |

| Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 1.6% | 6.4% | 5.4% | 1.19 | -3.3% |

| Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | 0.9% | 9.6% | 6.9% | 0.76 | 0.0% |

| Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO | 0.5% | 10.8% | 3.7% | 1.43 | -2.1% |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA | -1.0% | 5.5% | 6.5% | 1.07 | -2.7% |

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH | -1.3% | 11.2% | 6.0% | 1.64 | -1.2% |

| Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, RI-MA | -1.5% | -1.6% | 1.9% | 0.88 | 2.3% |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | -2.8% | -1.4% | 1.4% | 1.06 | -1.9% |

| Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | -4.5% | 1.5% | 0.3% | 1.10 | -3.5% |

| New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA | -4.6% | 2.8% | 3.2% | 0.90 | -6.2% |

| St. Louis, MO-IL | -4.8% | -1.7% | 1.4% | 1.05 | -0.9% |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | -6.1% | -0.8% | 4.0% | 1.00 | 0.0% |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | -6.3% | -4.3% | 2.5% | 0.89 | -3.3% |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL | -6.4% | -8.3% | 0.6% | 0.67 | -8.2% |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA | -7.1% | -3.5% | 3.1% | 0.98 | -5.8% |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR | -7.3% | -4.0% | 0.7% | 0.62 | -4.6% |

| Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH | -8.8% | -2.1% | 4.3% | 0.89 | 1.1% |

| Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI | -10.8% | -1.4% | 3.5% | 0.87 | -7.4% |

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL | -11.4% | -8.0% | -2.0% | 0.76 | -8.4% |

| Rochester, NY | -12.0% | -2.1% | 4.1% | 1.14 | -10.2% |

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | -12.6% | 12.4% | 8.3% | 3.18 | -4.8% |

| New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA | -16.0% | -7.4% | -2.4% | 0.74 | 0.0% |

| Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI | -17.7% | -10.3% | 10.5% | 1.42 | -3.4% |

| Analysis by Mark Schill, Praxis Strategy Group | |||||

| Data Source: EMSI 2012.4 Class of Worker – QCEW Employees, Non-QCEW Employees & Self-Employed | |||||

The LQ (location quotient) figure in the table above is the local share of jobs that are STEM occupations divided by the national share of jobs that are STEM occupations. A concentration of 1.0 indicates that a region has the same concentration of STEM occupations as the nation. The analysis covers 80 STEM occupations in all industries.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register . He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Computer engineer photo by BigStockPhoto.com.