Facebook‘s botched IPO reflects not only the weakness of the stock market, but a systemic misunderstanding of where the true value of technology lies. A website that, due to superior funding and media hype, allows people to do what they were already doing — connecting on the Internet — does not inherently drive broad economic growth, even if it mints a few high-profile billionaires.

Of course Facebook is a social phenomenon that has affected how people live and interact, but its economic impact — and future level of profitability — is less than clear. This stands in sharp contrast to Apple‘s iTunes, which has become a new distribution platform for small software companies and musicians, not to mention the role of Amazon in the distribution of books and other products.

From the standpoint of economic development, it’s time to focus on the growing divergence between two different aspects of technology. One is largely an information sector that focuses on such things as information software (think Facebook or Google), publishing and entertainment. For most journalists and urban theoreticians, this is the “sexy” sector, particularly since it tends to employ people just like them: younger, products of elite college educations, often living in “hip and cool” places like San Francisco, Manhattan or west Los Angeles.

Then there’s a larger, less-heralded group of workers that my colleague Mark Schill at Praxis Strategy Group has focused on: those in STEM (science-, technology-, engineering- and mathematics-related) jobs. These workers perform technology work across a broad array of industries, including but not limited to computers, media and the Internet, representing some 5.3 million jobs in the nation’s 51 largest metropolitan areas. This compares to roughly 2.2 million jobs classified as in the information sector in these 51 regions.

These STEM occupations are about harnessing technology to improve productivity in mundane traditional industries and the service sector. STEM workers are as likely, if not more so, to be working for manufacturers, retailers or energy producers as for software firms. These workers epitomize the notion of technology, as the French sociologist Marcel Mauss once put it, as “a traditional action made effective.”

The information sector may be increasingly important, but it is STEM workers, working in a diverse set of industries (including information), who hold the broader hope for the U.S. economy. Over the past decade, the information sector has created many stars, but about as many flameouts. Overall information employment peaked in 2000 at 3.6 million jobs; by 2011 this number had dropped by almost a million. Things have not much improved even in the current “boom”; between February and May this year, the sector lost over 8,000 jobs.

Essentially the information sector has created a huge amount of churn, as the nature of its employment changes with shifts in technology. For example, the software sector within information has seen real growth, adding some 10,000 jobs the past two years, while other parts of the information sector have suffered significant drops. These include, sadly for aged scribblers, traditional publishing, such as newspapers and book publishing, which has gone from nearly 1 million jobs in 2002 to under 740,000 in May of this year.

With Facebook stock in the tank, and other major social media sites languishing, the current “boom” may prove among the shortest-lived in recent memory. Shares of less well-anchored companies — meaning those with only a vague outlook for long-term profits — such as Zynga and Groupon have fallen dramatically. The market for the next round of ultra-hyped IPOs also seems to be dissipating rapidly. The carnage has led at least one analyst to suggest Facebook’s fall could “destroy the U.S. economy.”

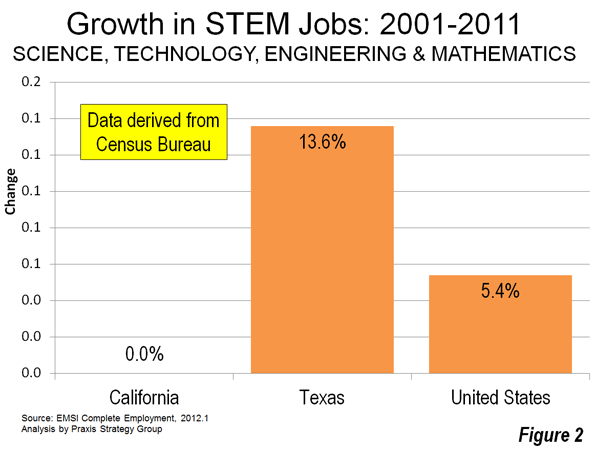

Fortunately the overall picture in technology is more hopeful than you’d understand from reading about social media startups. STEM employment has grown 3% over the past two years, more than twice the national average. In the 51 largest metros areas, 150,000 STEM jobs were added from 2009 through 2011. More important still, this reflects a long-term pattern: Over the past decade, STEM employment — despite a drop during the recession — expanded 5.4%.

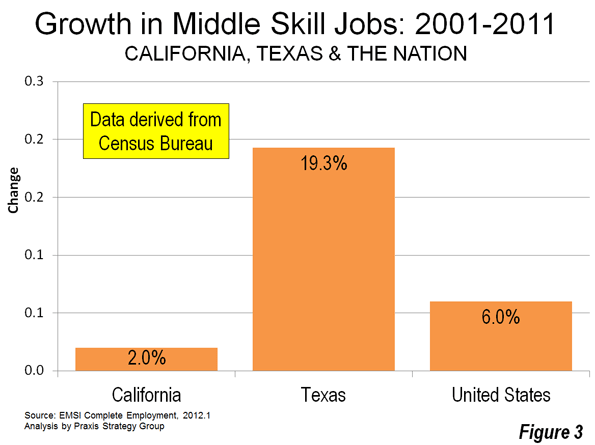

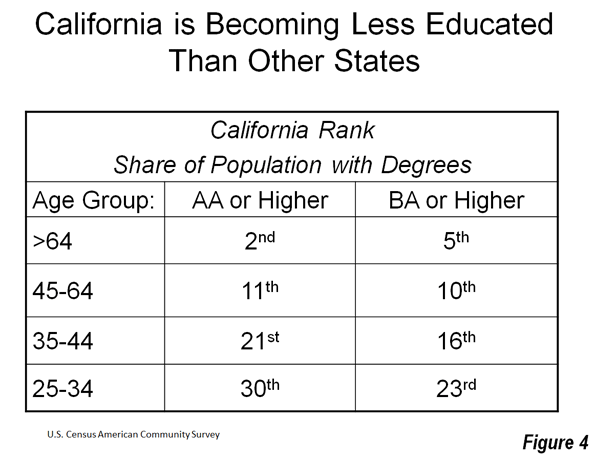

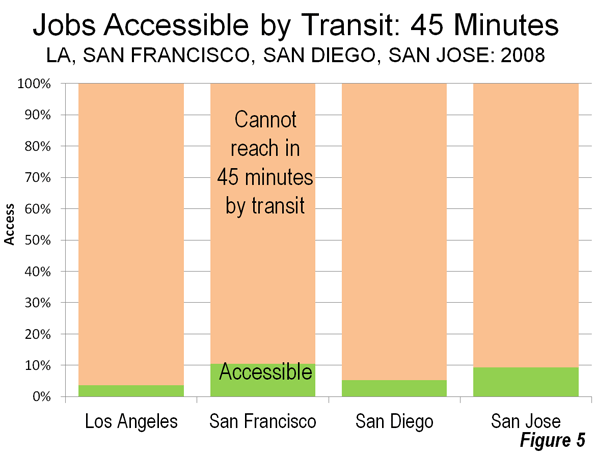

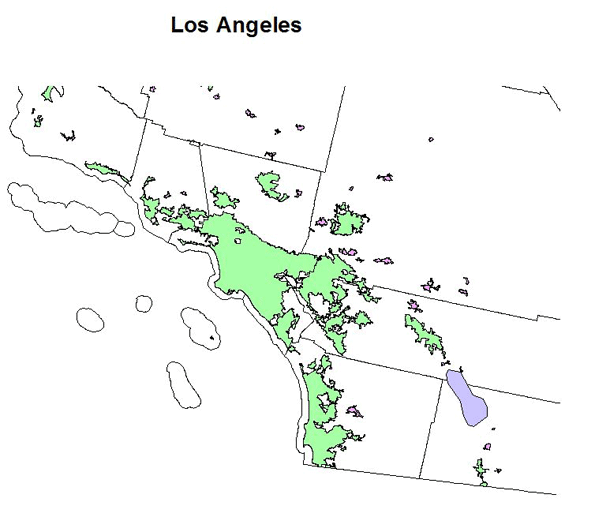

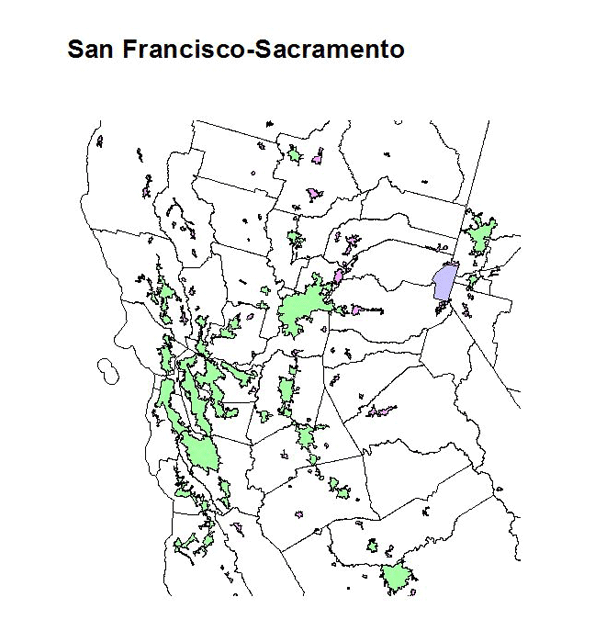

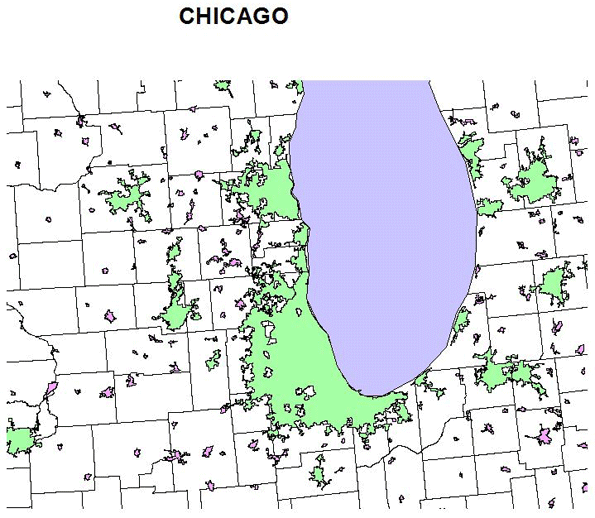

These two different classifications underpin geographical differences between and within regions. Sometimes the “hot” areas don’t look so great when it comes to actual job creation in these generally well-paying fields.

Silicon Valley’s social media boom, for example, may have propelled it once again, at least temporarily, into the ranks of the fastest-growing employment centers. Yet it’s not seeing the gains in STEM jobs that took place during earlier Valley booms in the ’80s or ’90s that were broader based, encompassing manufacturing and industry-oriented software. Indeed STEM employment in the Valley still has not recovered from the 2001 tech bust — the number of STEM jobs is down 12.6% from 10 years ago.

| Metropolitan STEM Job Growth, Sorted by 10-year Growth | |||

| MSA Name | 2001-2011 Growth | 2009-2011 Growth | 2011 Concentration |

| Las Vegas-Paradise, NV | 25.5% | -3.4% | 0.51 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 20.8% | 4.4% | 2.16 |

| San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX | 20.1% | 3.0% | 0.82 |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | 18.5% | 3.1% | 0.74 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | 18.3% | -1.6% | 0.55 |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 18.1% | 7.6% | 1.95 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 17.5% | 4.5% | 1.17 |

| Jacksonville, FL | 17.4% | 3.0% | 0.88 |

| Baltimore-Towson, MD | 17.2% | 3.9% | 1.36 |

| Raleigh-Cary, NC | 14.9% | 1.4% | 1.56 |

| Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX | 14.3% | 3.6% | 1.25 |

| Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL | 14.2% | -1.4% | 0.90 |

| San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA | 13.1% | 6.5% | 1.38 |

| Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, TX | 8.8% | 2.4% | 1.75 |

| Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC-SC | 8.1% | 2.1% | 0.97 |

| Columbus, OH | 7.8% | 3.8% | 1.32 |

| Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY | 7.7% | 2.4% | 0.96 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | 7.5% | -3.1% | 1.05 |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL | 7.5% | 2.8% | 0.73 |

| Indianapolis-Carmel, IN | 7.5% | 1.2% | 1.06 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 7.3% | 2.9% | 0.89 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 6.2% | 3.7% | 1.21 |

| Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN | 6.1% | 4.6% | 1.08 |

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA | 6.0% | -1.6% | 1.19 |

| Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | 5.6% | 4.3% | 0.77 |

| Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale, AZ | 5.4% | 1.5% | 1.00 |

| Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 5.2% | 4.2% | 1.24 |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA | 4.8% | 4.3% | 1.10 |

| Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO | 4.0% | 2.8% | 1.47 |

| Richmond, VA | 3.8% | 0.4% | 1.14 |

| Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, RI-MA | 3.6% | 2.4% | 0.90 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 3.1% | 3.6% | 1.07 |

| Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | 3.1% | 1.2% | 1.18 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 2.6% | 3.1% | 1.37 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | 2.4% | 2.0% | 0.88 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 2.2% | 0.3% | 1.19 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | 1.9% | -2.6% | 1.15 |

| New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA | 1.2% | 2.9% | 1.00 |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA | 0.8% | 3.7% | 1.60 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR | 0.0% | 0.7% | 0.56 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH | 0.0% | 4.8% | 1.64 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA | -2.2% | 1.7% | 0.98 |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | -2.3% | 0.2% | 1.04 |

| St. Louis, MO-IL | -3.5% | -1.4% | 1.05 |

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL | -3.9% | -3.4% | 0.70 |

| Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH | -4.9% | 1.2% | 0.93 |

| Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI | -5.2% | 1.1% | 0.96 |

| New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA | -6.7% | 3.6% | 0.71 |

| Rochester, NY | -8.9% | 2.1% | 1.19 |

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | -12.6% | 4.9% | 3.09 |

| Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI | -14.9% | 8.8% | 1.42 |

| Total in Top 51 Regions | 4.2% | 3.0% | |

Data source: EMSI Complete Employment, 2012.1. The “2011 Concentration” figure is a location quotient. That’s the local share of jobs that are STEM occupations divided by the national share of jobs that are STEM occupations. A concentration of 1.0 indicates that a region has the same concentration of STEM occupations as the nation.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

This piece originally appeared in Forbes.