Throughout the high income world, in this age of cities, many urban centers continue to shrink. This is particularly true in municipalities that have been unable either to expand their boundaries or to combine with another jurisdiction, subsequently running out of new developable land.

For example, the city of Paris (as opposed to the metropolitan area or urban area, see Note) lost a quarter of its population between 1954 and 1999, while the loss in some core districts (arrondissements) was 75 percent. Copenhagen, which is often considered one of Europe’s most vibrant municipalities lost more than one-third of its population between 1950 and 2000. Other core municipalities have lost more than one-half million people, such as, London, Seoul, Glasgow, Berlin, Osaka, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia and St. Louis.

City of St. Louis Population Loss: Yet no city which achieved the scale of a half million residents has lost a larger percentage of its population in peacetime than St. Louis. To some extent, this is a very old problem for a city that was once the largest in the Midwest but was passed in 1880 by Chicago.

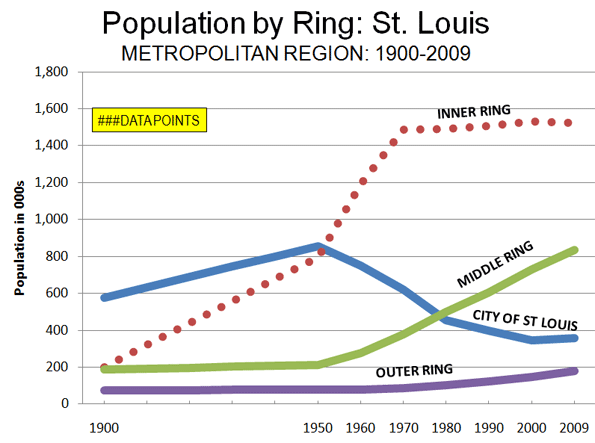

In 1950 the city population peak at 857,000 people and ranked 8th among the nation’s municipalities. By 2009, the latest estimates, the population was 357,000 (ranked 48th in the nation), a decline of nearly 60 percent from the peak.

Metropolitan Population Gain: But as is the case for many “shrinking cities,” the region outside the municipal boundaries has continued to grow. In1950, the population of the metropolitan region (as currently defined) was 1,940,000. By 2009, the metropolitan region had grown to 2,890,000, for a population increase of nearly 1,000,000 (more than a 50 percent increase). St. Louis is a bi-state metropolitan area, with three quarters of the population living in Missouri and the balance in Illinois, a ratio than has been largely unchanged since 1900.

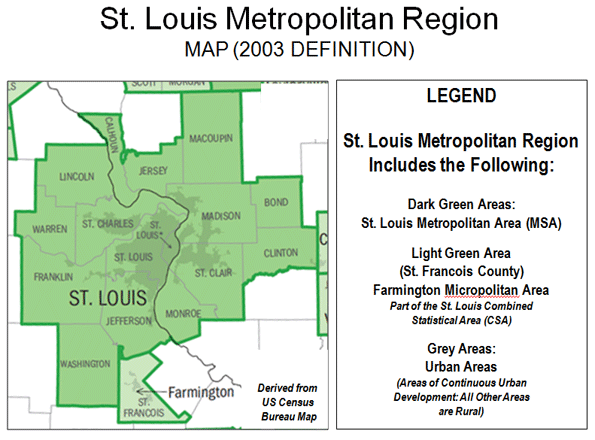

The metropolitan region (or combined statistical area) includes the city of St. Louis, (a county equivalent jurisdiction), 8 counties in Missouri and 8 counties in Illinois. The St. Louis metropolitan region covers approximately 9,100 square miles (Figure 1), of which the principal urban area (area of continuous urbanization) covered 829 square miles (9 percent of the metropolitan region).

As in the case of virtually all large high-income world metropolitan areas, population growth has principally occurred on the suburban fringe. For example, from 1965 to 2000, 110 percent of the growth in major metropolitan areas of Western Europe was in the suburbs, more than in the United States (90 percent since 1950).

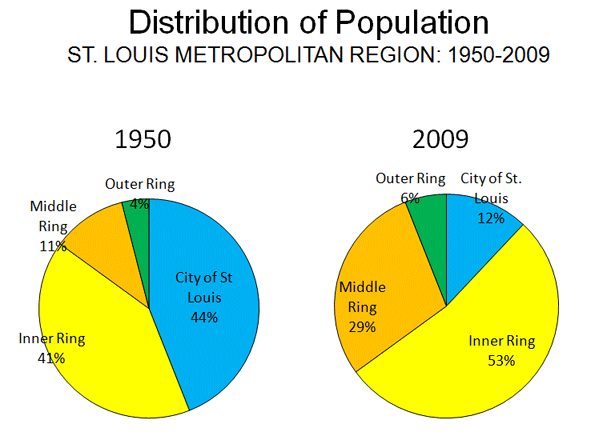

Distribution of Population: Even by these standards, St. Louis may be an extreme case. In 1950, 44% of the region’s population was in the city of St. Louis. The inner ring the counties of St. Louis, St. Clair (Illinois) and Madison (Illinois), accounted for another 41% of the population. Thus 85% of the metropolitan region’s population lived in the city or the inner ring counties. The other 15% lived in middle ring and outer ring counties.

By 2009 the population of the city and the inner ring counties had fallen to 65% of the region. The city and county of St. Louis (which were combined until 1876), reached a combined population peak in 1970 and has lost 225,000 people since that time, falling below the 1960 census total.

The middle ring counties represented 29% of the population while the outer ring counties had 6% of the population (Figure 2) in 2009. During the 2000s, the middle ring counties added more than 130,000 residents, while the city added 10,000.

Consistent with the trend since the late 1950s, nearly all of the metropolitan region growth occurred outside the city and the inner ring between 2000 and 2009. The city is estimated to have accounted for 7% of the region’s growth. The inner ring counties actually shrank while the middle ring counties accounted for 76% and the outer ring counties 22% of the growth (Table 1 and Figure 3) for the region.

| Table 1 | ||||

| St. Louis Metropolitan Region: Population Trend | ||||

| 1900-2009 | ||||

| Sector |

1900

|

1950

|

2000

|

2009

|

| METROPOLITAN REGION (CA) |

1,039,543

|

1,942,848

|

2,757,377

|

2,892,874

|

| HISTORIC CORE |

575,238

|

856,796

|

346,904

|

356,587

|

| City of St. Louis |

575,238

|

856,796

|

346,904

|

356,587

|

| INNER RING |

201,419

|

794,651

|

1,531,692

|

1,524,482

|

| St. Louis Co. |

50,040

|

406,349

|

1,016,364

|

992,408

|

| Madison Co. (IL) |

64,694

|

182,307

|

259,120

|

268,457

|

| St. Clair Co. (IL) |

86,685

|

205,995

|

256,208

|

263,617

|

| MIDDLE RING |

187,384

|

213,394

|

730,563

|

833,706

|

| Franklin Co. (MO) |

30,581

|

36,046

|

94,059

|

101,263

|

| Jefferson Co. (MO) |

25,712

|

38,007

|

198,740

|

219,046

|

| St. Charles Co. (MO) |

24,474

|

29,834

|

286,171

|

355,367

|

| Bond Co. (IL) |

16,078

|

14,157

|

17,650

|

18,103

|

| Clinton Co. (IL) |

19,824

|

22,594

|

35,536

|

36,368

|

| Jersey Co. (IL) |

14,612

|

15,264

|

21,655

|

22,549

|

| Macoupin Co. (IL) |

42,256

|

44,210

|

48,989

|

47,774

|

| Monroe Co. (IL) |

13,847

|

13,282

|

27,763

|

33,236

|

| OUTER RING |

75,502

|

78,007

|

148,218

|

178,099

|

| Lincoln Co. (MO) |

18,352

|

13,478

|

39,254

|

53,311

|

| St. Francois Co. (MO) |

24,051

|

35,276

|

55,743

|

63,884

|

| Warren Co. (MO) |

9,919

|

7,666

|

24,721

|

31,485

|

| Washington Co. (MO) |

14,263

|

14,689

|

23,410

|

24,400

|

| Calhoun Co. (IL) |

8,917

|

6,898

|

5,090

|

5,019

|

| Metropolitan Region: Combined Statistical Area (2009 Definition) | ||||

Despite often well-orchestrated impressions to the contrary, the continuing dominance of suburban population growth in the St. Louis metropolitan region mirrors the experience in other major metropolitan areas across the nation.. This growth has not been, as is often supposed, at the expense of the city. Over the past sixty years suburban growth was actually three times the total net loss suffered by the city. Increasingly when people move to St. Louis, they actually mean that they are coming to the suburban periphery.

Domestic Migration: Overall in the past decade, the St. Louis metropolitan region experienced only a modest domestic migration loss – far less than many other regions . Approximately 1.3 percent of the 2000 population, or 35,000 people moved from St. Louis to other parts of the nation. By comparison, in similar sized and sunny San Diego, the domestic migration loss was 127,000, with a percentage loss more than three times that of St. Louis. Who could have imagined that in a decade, Los Angeles would lose 1.3 million more domestic migrants than St. Louis and New York 2 million more (granted, from much larger bases).

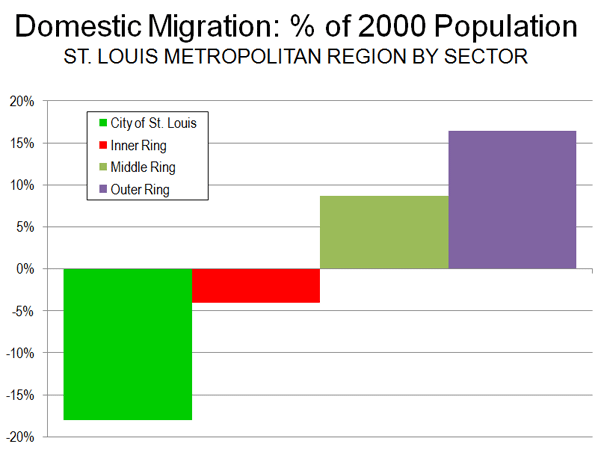

During the 2000s, the domestic migration trends within the St. Louis metropolitan region reflected the national trend of migration from core areas to the suburbs. According to US Census Bureau estimates, the 2000 to 2009 in domestic migration loss in the St. Louis metropolitan region was distributed as follows (Figure 4):

- The city of St. Louis has lost a net 63,000 domestic migrants (18.0 percent of its 2000 population)

- The inner ring counties have lost a net 59,000 domestic migrants(4.0 percent of the 2000 population), 57,000 of which were lost in St. Louis County

- The middle ring counties gained a net 64,000 domestic migrants with a gain of 45,000 in St. Charles County (8.7 percent of the 2000 population).

- The outer ring counties gained a net 24,000 domestic migrants (16.4 percent of the 2000 population) with nearly one half of the gain (11,000) in Lincoln County.

Net international in-migration was the one bright spot for the city and inner suburbs, which gained the bulk of the 30,000 immigrants who came to region over the past decade (Table 2). But this was not nearly enough to balance the losses from domestic migration.

Ultimately the St. Louis story reflects the deeper reality seen across the high-income (and even in some low and lower income world metropolitan areas, as future installments will indicate), albeit somewhat more exaggerated. Many core cities continue to stagnate or even shrink, but their regions remain vibrant, expressing a form of urbanism that, while often unappreciated, remains vital and expansive.

——–

Note: Metropolitan areas are composed (outside New England) of complete counties or county equivalent jurisdictions. They include substantial rural expanses, which are economically tied to the principal urban area (the largest urban area in the metropolitan area). An urban area is an expanse of continuous urbanization, and contains no rural territory.

Photo: St. Louis skyline (by author)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”