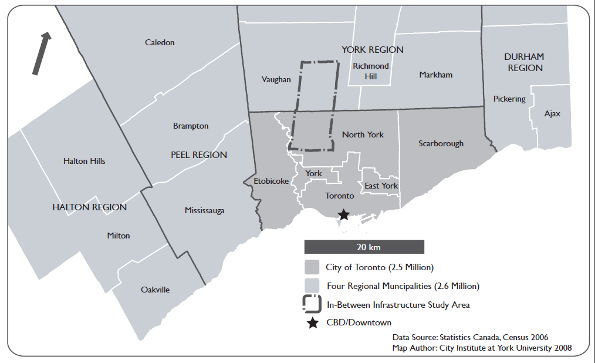

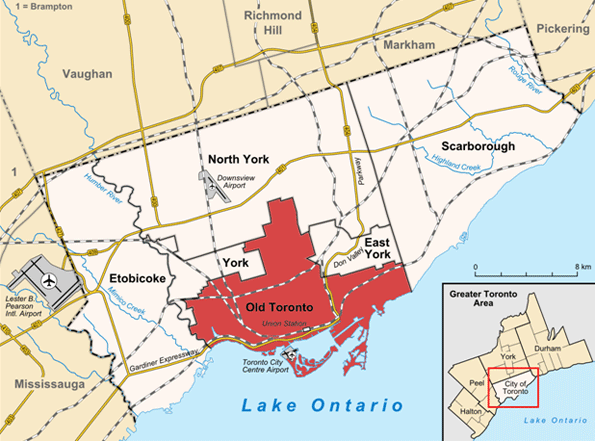

In my pre-election piece on the Toronto election, I discussed the city’s lingering malaise. It developed slowly but its roots can be traced to the 1998 amalgamation that swallowed up five suburban municipalities. This led to a six folds expansion of city boundaries and a tripling the population base. This amalgamation was initiated by the province of Ontario as a cost saving measure and faced major local opposition. Citizens and politicians were concerned that the benefits of the alleged efficiency saving would be outweighed by the negative impact of losing local decision making powers. The recent Toronto municipal election bore out this concern.

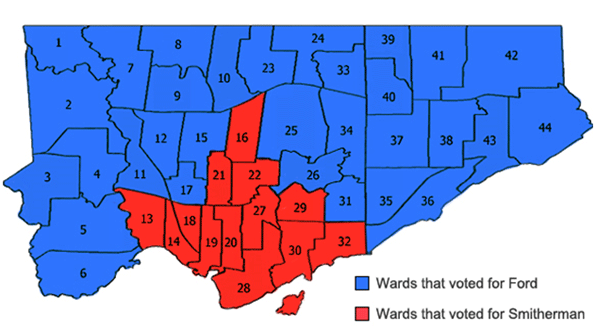

In the October 25th election, Torontonians were presented with two dramatically different visions. The first vision was presented by former Liberal Ontario cabinet minister George Smitherman. A self-described progressive, Smitherman appealed mainly to voters in the downtown core of Old Toronto. He stood for issues such as improved bicycle lanes, renewal of the downtown waterfront, and improving social housing conditions. The second version was presented by maverick councilor Rob Ford, who represented a ward in the former City of Etobicoke. Ford’s message was simple: it’s time to stop the “gravy train” at City Hall. While he had elaborate platforms on many issues, cutting waste at City Hall was his ubiquitous message.

Despite Toronto’s social democratic image, Rob Ford won a crushing victory. Ford earned 47% of the vote, while Smitherman ended up with 35%. Far left candidate Joe Pantalone (known primarily for attempting to stop businesses from opening in his own ward) managed to capture 12% of the vote.

Aside from the shock that a partisan conservative won in Toronto, there are two other significant developments. Both front runners were significantly more fiscally conservative than the current administration. Ford and Smitherman represented constituencies desperately seeking change. Smitherman’s base was frustrated with the inability of the city to provide the services that they want efficiently. Ford’s base was angry that the city is providing many of these services in the first place.

Not surprisingly the results broke down along specific geographic lines. Ford won an outright majority of votes in every single ward outside of Old Toronto. Within the old boundaries, Smitherman won 13 of the 16 wards. The three Old Toronto wards Ford won are all on the fringes of the Old City.

In 1997, the newly amalgamated city went to the polls for the first time. Conservative former North York Mayor Mel Lastman narrowly defeated social democratic former Old Toronto Mayor Barbara Hall. Since then, downtown oriented social democrats have controlled the city ever since.

Clearly this result shows that the concerns expressed by the opponents of amalgamation were largely valid. Amalgamation failed to create cost savings, and has created a dysfunctional megacity. Rather than having six municipalities where voters are focusing on solving local problems, we have one gigantic city with the core and the suburbs fighting for their share of the public purse. This leads to the schizophrenic policy decisions we see today.

Before amalgamation, there were six different versions of Toronto life that one could choose from. If you didn’t like living in high tax Toronto, you could live in Etobicoke. If Etobicoke’s bylaws and business taxes were hurting your business, you could move to North York. Now all people in the Toronto area can do is vote the bums out on election day, or get out of the area altogether. This isn’t a viable long-term solution.

The problems are systemic, and cannot be solved so long as the megacity exists. This extends beyond the fact of the impossibility of satisfying the core and the suburbs at the same time. The megacity allows public sector unions to literally hold 2.5 million people hostage whenever they feel like it. A notorious strike last summer lead to a month without garbage collection in the entire city. The 24,000 strikers also shut down parks and recreation services, daycare, provision of municipal licenses, health inspections, animal services, and forced a 25% reduction in ambulance services. In 2008, the transit union called a last minute strike at midnight on a Friday night, grinding the city to a halt. These are just two examples of how powerful Toronto public sector unions have become. The only reason strikes aren’t more frequent is that the city typically gives them whatever they want in order to avoid chaotic strikes. De-amalgamation would not only allow more local control over policy, but would help fray the noose that the unions have tied around the city’s neck.

Downtown progressives gripe over how Rob Ford is going to destroy their city, but they should take a minute to think about what some of their policies have been doing to suburbanites for years. They have imposed high taxes, and burdensome regulations on the amalgamated cities, as well as a myriad of new bylaws. Some of these policies make sense in Old Toronto. For instance, dissuading automobile usage in the congested core makes sense. Doing so in the suburbs does not. It might make sense to regulate trees on private property in a crowded downtown neighborhood. Not so much in a new subdivision. One-size-fits-all policies don’t work across a city as large and diverse as Metropolitan Toronto.

Now that the suburbs have wrought their revenge on the old city, progressives need to recognize that de-amalgamation is not just a fantasy of libertarians and angry suburbanites. It is a prerequisite to restoring sound public policy reflecting the preferences of individual communities. Railing against Rob Ford won’t fix the problem. Rob Ford is what the suburbs want. As long as the megacity lives, Toronto will elect a Rob Ford type every now and then.

The only way to stop this pattern of alternating, divergent visions is by de-amalgamation. Critics will use metaphors such as ‘unscrambling an egg’ to illustrate the difficulties of de-amalgamation. No one should believe that de-amalgamation would be easy. But there will never be a better time than now to take the necessary step of de-amalgamation. A few years of chaotic governance would be worth the long run benefit of restoring local control.

Downtown Toronto photo by Astro Guy

Steve Lafleur is a public policy analyst and political consultant based out of Calgary, Alberta. For more detail, see his blog.