Los Angeles area transit officials celebrated 20 years of urban rail at a Staples Center event on July 23. Over the past 20 years, Los Angeles has opened 2 metro (subway) lines, 4 light rail lines and two exclusive busways (though apparently busways aren’t worth celebrating). Surely, there is no question but that Los Angeles has been successful in opening a lot of new transit infrastructure.

At the same time, however, The Los Angeles Times reported that Professor James Moore of the University of Southern California, blames the disproportionate financial attention paid to rail projects reduced transit ridership by 1.5 billion (with a “b”) over the same period. The reason is, as Tom Rubin put it, is that many more people can be carried for the same money on buses, “Had they run a lot of buses at low fares, they could have doubled the number of riders.” Rubin was chief financial officer of the Southern California Rapid Transit District, one of the two predecessors of the present transit agency (MTA). The other was the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, to which I was appointed to three terms.

Transportation experts were also quoted to the effect that the rail system has done little to reduce traffic congestion or increase the use of mass transit much beyond the level in 1985, when planning for the Metro Blue Line began. Indeed. Traffic congestion has gotten much worse, and traffic volumes have increased materially. Our recent article showed that transit market shares had declined.

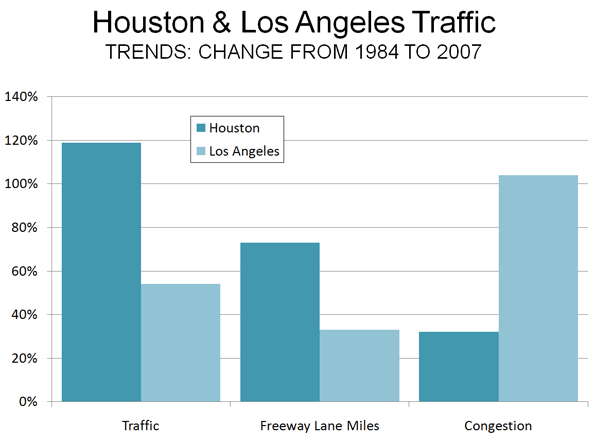

These results are in stark contrast to Houston, which in 1984 had the worst traffic congestion in the nation. Houston set about to solve the problem by expanding its roadway capacity. Since 1984, Houston’s traffic grew twice as fast as that of Los Angeles, and population grew three times as fast (at least in part because many Californians were moving to Texas). Houston also added freeway mileage at double the percentage rate of Los Angeles. The reward was an increase in traffic congestion less than one-third that of Los Angeles (Figure). The most recent INRIX Scorecard shows Los Angeles traffic congestion to be more than 2.5 times as intense as Houston’s.

Spending money on the right things makes a big difference. One can only wonder how different things might have been if Los Angeles had invested in the capacity people need (more roads) rather than in politically correct transit facilities that have no potential to reduce traffic congestion or to improve mobility and economic performance.

There is a lesson from Los Angeles experience both for other areas and other government functions. The test of government performance is outputs, not inputs. Thus, it is appropriate to celebrate large transit market share increases or significant improvements in student achievement, not how many miles of rail are built or how much money is spent on education.

There is a lesson from Los Angeles experience both for other areas and other government functions. The test of government performance is outputs, not inputs. Thus, it is appropriate to celebrate large transit market share increases or significant improvements in student achievement, not how many miles of rail are built or how much money is spent on education.

Photograph: Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley (by the author)

The fact is that

The fact is that