When I was a kid back in 1971 I lived in Anaheim, California where my mom was a waitress at a local amusement park. Exploring Orange County as an adult recently it all felt more or less the same as I remembered – only more so. The primary adjective has always been beige. The last vestiges of orange groves that still lingered in my youth are long gone, but the tidy neighborhoods of modest tract homes, strip malls, and motels are all still there behind the shiny new stuff.

I was asked to write about Orange County as part of a land use and transportation conference so I went straight to the new ARTIC intermodal transit center. The boosters for ARTIC use words like “iconic,” “transformative,” “unique,” “prestigious,” and “catalytic” to describe the transit hub. There’s a lot of talk about the cooperation of numerous agencies and private firms that all collaborated to make the $185 million project happen. The structure is about getting people excited about Anaheim. The nuts and bolts of transportation itself are peripheral.

Cut to the poor bastard out there somewhere on an anonymous street in Orange County waiting (and waiting, and waiting) for a bus to arrive so he can catch his transfer and get from Point A to Point B. The really transformative thing that would get him excited about transit would be more frequent service and a trip that took twenty minutes instead of an hour and a half. ARTIC does nothing for him. But that was never the point. ARTIC isn’t about transit.

I was staying in nearby Garden Grove six miles away from ARTIC and I decided to test the process of moving around Orange County by public transit. An internet query described a trip of an hour and five minutes by bus. I sat at a bus stop and waited with my fellow travelers and chatted with them about their daily experience. The bus got them where they needed to go, but it wasn’t great. After thirty minutes the bus appeared. I calculated the wait for the transfer along the way and then the trip back again and realized the bus would suck up three hours of my day. And I was going to be cutting it close for an appointment that afternoon.

Traveling by bike was going to take thirty seven minutes and it was all flat. I live in a transit rich neighborhood in San Francisco and I prefer my bike to transit most of the time. But as an out-of-town visitor I didn’t have a bike. I searched for bike rental facilities and there weren’t any near me. And there was the reality that most of the trip would be on the side of high speed eight lane arterials. It would have been doable, but not amazingly fun.

Driving the six miles to ARTIC would take thirteen minutes so I walked back to my car. Here’s where I got a glimpse in to the prevailing culture of Orange County. I parked on a quiet residential side street and when I reached my car a note had been left on my wind shield. I was parked legally on a public street that had no restrictions. I wasn’t blocking anyone’s access and the street was mostly empty. The house in question had a two car garage and a driveway that could accommodate half a dozen vehicles. The parking problem wasn’t physical. It was emotional. Suburbanites don’t like their psychic space interfered with by interlopers. This goes a long way to explaining the transportation dynamics in the region.

Google

Google

Google

Google

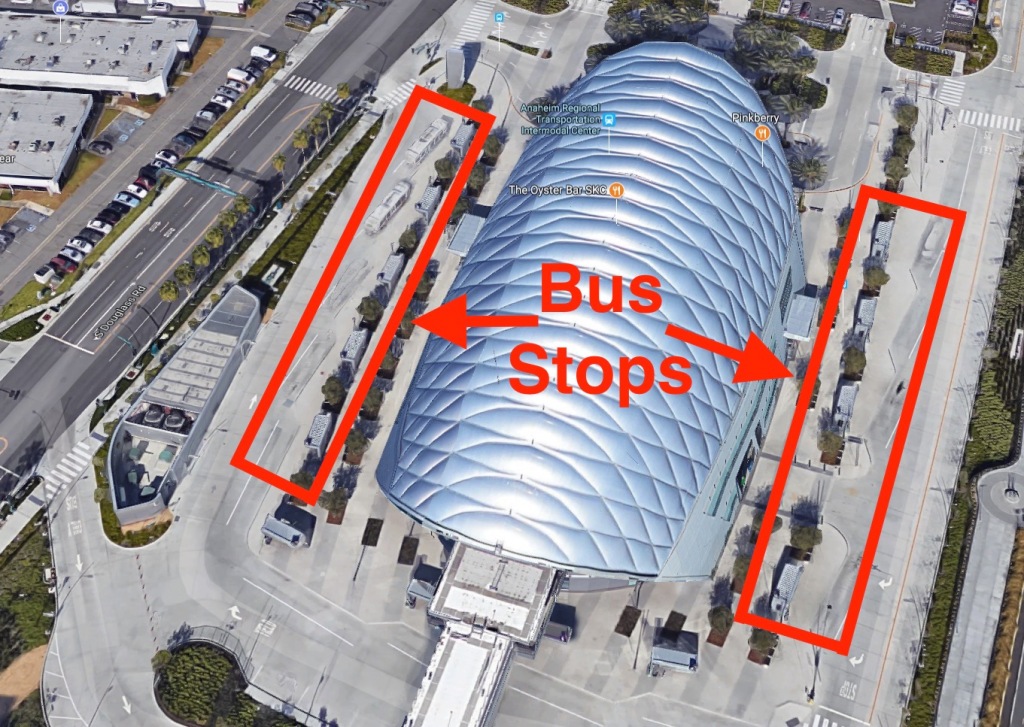

ARTIC is so big that it’s easier to get a feel for the place on Google rather than on the ground. The train platform is at one end, the bus stops are on either side, there’s a bike path along one edge of the property, and parking is everywhere. You’ll notice that the elegant structure itself has no real function. It’s purely decorative and designed to make a statement on the skyline. It could be replaced by a few porta-potties and a food truck and the transit stuff would be totally unaffected.

Google

Notice the transit hub is in the middle of absolutely nothing. The site is bound by the Santa Ana River on one side, a giant freeway on the other, and massive parking lots for Angel’s Stadium and Honda Center. I dare anyone to walk from one of these buildings to another. Even if I had managed to take a bus or train to ARTIC the destination wouldn’t have rewarded the effort.

Google

During the boom of the early 2000s plans were drawn up to transform the aging industrial properties in the area to higher value residential, commercial, and professional uses. The authorities in Anaheim built ARTIC as a shiny temple to lever development of the nascent urban center called the Platinum Triangle. Those plans crashed with the 2008 financial crisis and are only now ramping back up.

The predominant design criteria for most of these new buildings involves suburban expectations. The interiors of the apartments as well as the private amenities within these complexes are quite nice and reflect the kinds of things affluent people have come to expect from single family homes in gated communities: greenery, swimming pools, convenient parking, privacy and security protocols. It’s all just been super sized at higher density. But when you’re outside of these buildings you stand between fortified shrubbery and ten lanes of traffic. People drive to the parking deck at the shopping mall or office park which is also hermetically sealed. It ain’t Paris.

Ridership at ARTIC is considerably lower than anticipated for the simple reason that the physical environment is brutal for anyone who isn’t in a car – and that isn’t likely to change for a very long time. The density is coming. The urbanism isn’t. As I explored these new complexes I discovered that each of the lobbies and sales offices were accessed by the parking garage rather than the street. No one expects future residents to ever arrive on foot. This is Orange County… I talked to many of the low wage workers like the parking attendants. They all live in other more affordable cities at some distance. I asked them if they take transit. Not if they can possibly avoid it.

Here’s how transit really works in Anaheim. Specific vehicle fleets take certain kinds of people to particular sorts of destinations. Both the populations and the destinations are cherry picked. The right kinds of people get to where they need to go quickly and efficiently. Everyone else… Suck it up.

This piece first appeared on Granola Shotgun.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He’s a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.