Who would have thought that city planners in Oklahoma City would be more bike and pedestrian friendly, and better at taming car traffic, than those in Rome? In Oklahoma City, Mayor Mick Cornett has reordered the city’s transportation priorities away from cars, and toward exercise and fitness. Speaking of OKC’s car-centric era, the mayor said “We had built an incredible quality of life, if you happen to be a car. But if you have to be a person, you are combatting the car seemingly at every turn.” By contrast, Rome remains wedded to the automobile, to the point that it’s turning into the Eternal Parking Lot.

Cornett has added sidewalks and bike lanes, and even put in some kayak parks downtown, leading OKC residents through a collective weight loss campaign that he estimates to have totaled one million pounds. Rome, meanwhile, must rank with Moscow, Dubai, and Lagos as one of the most automobile-dominated cities in the world.

What madness possessed me to take a bicycle into Rome? I had biked from Florence to Siena, across the heart of Tuscan wine country, and was simply continuing on two wheels. The reason I know: I went there on a bike.

Outside the classical city I could skirt cobblestones and ride in bus lanes (Rome has a few bike paths, but they begin and end nowhere, a bit like the country’s politics).

Once inside the famed city gates, slick cobblestones made biking feel like a ride on a roller-coaster off the rails. As I headed into central Rome I knew the cobblestones and the taxi drivers might make it a rough journey, but I had forgotten the extent to which Rome is the world capital of lane-changing, that frantic need to get around every slow or parked car.

Knowing Rome fairly well I switched to back alleys and one-way streets, where I discovered that not only does the city’s traffic have aspects of colliding atoms, but that the emergence of economical Smart Cars and small electric vehicles has made it possible for many more Romans to squeeze their motorized vehicles into the city’s historic corners.

No matter which historic piazza I crossed or which road I took I came face-to-face with one of the motorized creatures — some the size of golf carts — that Romans drive literally everywhere.

If Caesar’s assassins were now to stalk him near the Forum, I am sure they would do so in tiny Fiats and, while stabbing him, park on the sidewalk with their emergency lights flashing.

Everywhere I went in Rome, cars were littered. There were cars all around the Vatican, in the small squares of Trastevere, around the Colosseum, and up against the Forum.

Not only is Rome the empire of errant cars, its sidewalks — perhaps laid out to confuse invading Huns — have to be the worst in Europe. Walking two abreast is impossible. Instead, between the cars careening around medieval piazzas or parked against doorways, pedestrians must walk single-file, like a retreating army.

The solution to Rome’s clogged arteries is to ban (during the waking hours) cars, trucks, motor scooters, tour buses, four-by-fours, and Harleys from the historic downtown, and to return the small cobblestoned streets to their rightful owners: classical architecture and pedestrians.

For traveling through and outside the original city center, Rome has an underground metro, trams, and many buses which could stick to the main avenues. It might inconvenience some, but for the majority, and that includes the global heirs of the Roman republic, the city would again be a delight.

Venice solved the problem of burdensome traffic by filling its streets with water. Other European cities — the old town of Dubrovnik, Orleans in France, and Copenhagen come to mind — have successfully put pedestrians and bicycles first.

If its cars were evicted, Rome would become one of the world’s great open air museums, on a par with the old city of Jerusalem, parts of Marrakech, and with some sidewalk areas in Paris, although I doubt Rome will ever break with the automobile.

Rome is sinking under the weight of its exhaust pipes not only because of its traffic. The city shares the nation’s political problems: one hundred and fifty years after its independence, Italy is still best understood as a fragmented state, the Yugoslavia of the European Union, with a dysfunctional judiciary, parliament, executive branch, and treasury, and the fear that the center will not hold.

To understand the level of executive and parliamentary incompetence, consider that, since the Fascist government was toppled in World War II, about forty-three men have served as prime minister, and the parliament has had more than sixty changes to its governing coalition. Only one government in this period has served out its five-year term.

The biggest reason for Italy’s political stalemate is that the country’s north-south divide has remained unresolved, some would say since Garibaldi marched on Rome in 1862.

Northern Italy has a prosperous manufacturing base, a balanced budget, low debt to its GDP, dynamic cities (Milan, Turin, Venice, Bologna), and strong tourist and export revenue. The south, which includes Naples and Sicily, is a huge consumer of government subsidies, heavily reliant on inefficient agricultural systems, and has less manufacturing than the North. Rome is a nether world between the two blocs.

Youth unemployment in Naples is said to be 50 percent, and GDP per capita is some $40,000 less in the south than in the north. Sicily today may have less to fear from the mafia, but greater danger from joblessness.

The specter of Italy dividing along its north-south seam — as if after an earthquake in the Apennines — is, I believe, the reason that no one wants a strong federal government in Rome. Little government is thought to be less offensive to most than at even some degree of functional government would be.

Rome is the symbol of this fragmented state, with its allure of past and future greatness, and its present vanishing under a layer of soot, corruption, and waste.

David Gilmour ends his excellent history, The Pursuit of Italy, with, “Yet the millennia of [the Italians] past and the vulnerability of their placement have made it impossible for them to create a successful nation-state.”

In Oklahoma City, my favorite mayor can expand the sidewalks and lay down more bike lanes, much as he can argue for a balanced budget. In Rome, however, no one can take on the car lobby because no one, politically, is out strolling arm-in-arm. For one thing, the sidewalks don’t allow it.

Matthew Stevenson, a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine, is the author most recently of Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited, a collection of historical travel essays, and Whistle-Stopping America. His next book, Reading the Rails, will be published in 2016. He lives in Switzerland.

Flickr photo by Andrew Moore: Parking, Italian Style — A Fiat 500 in Rome

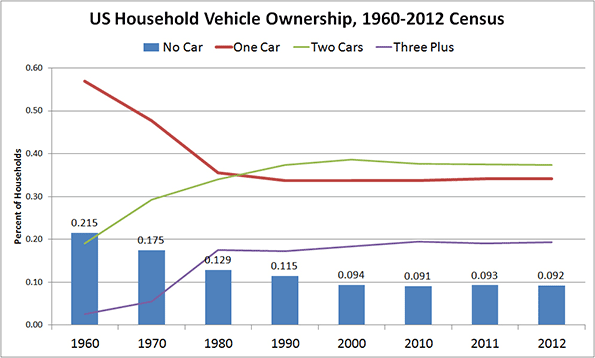

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5.

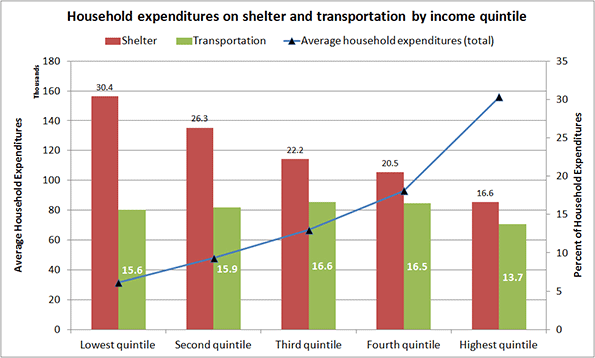

Chart 1 Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Transportation Energy Data Book. Table 8.5. Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012.

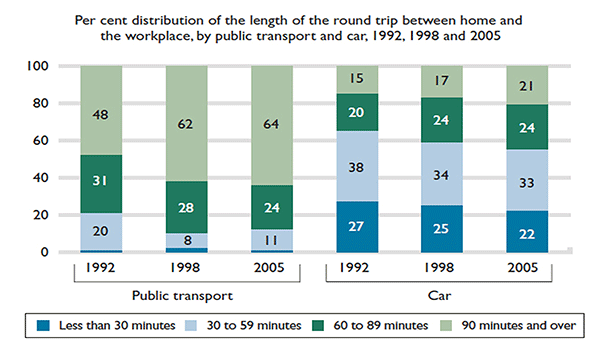

Chart 2 Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Household Spending. Table 2: Budget Shares Of Major Spending Categories By Income Quintile, 2012. Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005.

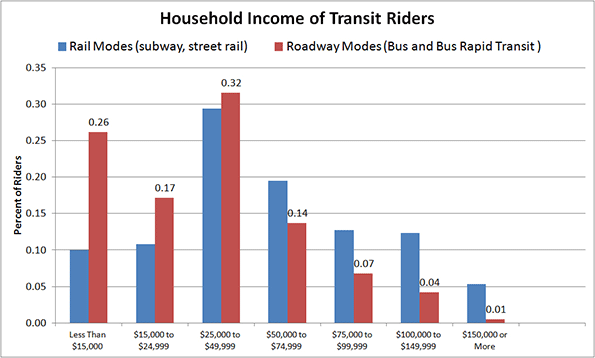

Chart 3 Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, Trip Duration, 1992, 1998, and 2005. Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007.

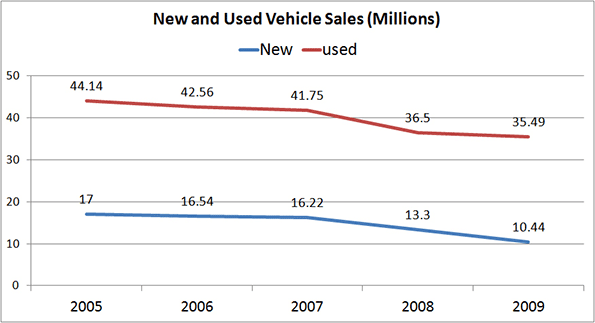

Chart 4 Source: American Public Transportation Association, A Profile of Public Transportation Passenger Demographics and Travel Characteristics, 2007. Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010.

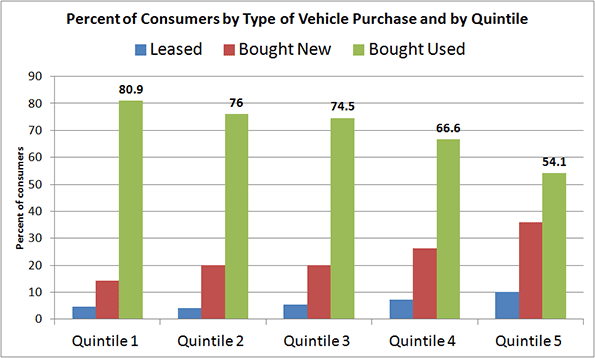

Chart 5 Source: NIADA’s Used Car Sales Industry Report; Relative Size of Car Markets for New and Used Cars, 2010. Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

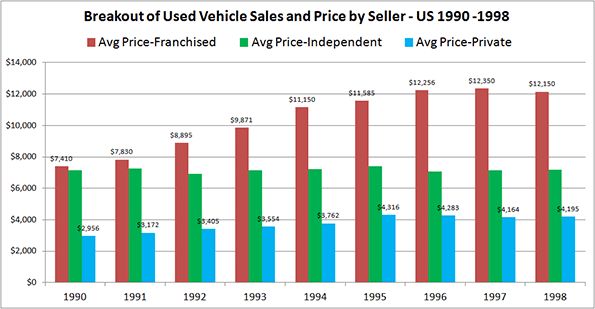

Chart 6 Source: Laura Paszkiewicz, The Cost and Demographics of Vehicle Acquisition, Consumer Expenditure Survey Anthology, 2003 (61) Division of Consumer Expenditure Surveys, US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.

Chart 7 Source: The Used Vehicle Market in Canada, DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc., 2000.