Honolulu is set to construct an ambitious urban rail project. It’s a $5.125 billion behemoth that this metropolitan area with less than a million residents may not be able to afford.

Honolulu’s Beleaguered Residents

Critically, there is plenty of competition for the scarce dollars that Honolulu residents have to spare. The city’s basic infrastructure is in bad shape.

(Sewer) Water, Water Everywhere: A consent decree signed between local officials and the Environmental Protection Agency requires major upgrades to the sewer system. Sewer overflows are not unusual. Just a few days ago, 51,000 gallon raw sewage spilled into a local stream. The state issued a brown water alert for the entire island of Oahu (which is also the combined city and county of Honolulu), including Waikiki Beach and all other beaches. As of this writing, the brown water advisory has not been cancelled. Just in the last year, the state has reported 17 sewage spills and four brown water alerts. For this to happen in a highly tourist dependent economy is nothing short of astounding.

More than Leaky Pipes: The city’s water system is in need of major upgrades. From 2004 to 2009, water main breaks were virtually a daily occurrence. In an effort to solve the problem, the city has raised water rates 60 percent in the last five years and plans another 70 percent increase over the next five years. How much more will be required after that is anyone’s guess. "How are people going to make it? I just don’t know" reacted City council Budget Chair Ann Kobayashi.

Unfunded Government Employee Liabilities: In just three years, unfunded city and county employee pension and retiree benefits have risen from $15,000 to $21,000 per Honolulu household. The state’s actuarial consultant says things are going to get worse. The demographics are skewed against financial control, since people are living longer, and the number of retirees is rising relative to the workers who must pay (most of whom cannot even dream of such rich benefits). All of this means higher tax bills for Honolulu households.

High Cost of Housing, High Cost of Living: Honolulu residents already endure the most unaffordable housing in the nation, with median house prices 8.7 times median household incomes. That is three times Dallas-Fort Worth. Honolulu’s overall cost of living is also the highest in the nation, outside six metropolitan areas in the greater New York and San Francisco Bay Areas. Honolulu residents pay $1.41 to buy what $1.00 buys in St. Louis, 1.24 for each $1.00 in Austin and $1.21 for each $1.00 in Phoenix.

Choices: This is not about easy choices. The sewer remediation, water system maintenance, government employee pension and government employee retiree health care benefits are mandatory. The rail expenditures are not.

The Rickety Rail Project

Yet the city of Honolulu would tax its residents even more to pay for a 20 mile rail line to empty farmland well beyond the urban fringe. This is a project not unlike the early 1900s land speculation schemes of Henry Huntington in Los Angeles and the Sweringens of Shaker Heights (Cleveland). There is, however, one important difference. The Huntington and the Swearingens bet their own money. Honolulu is betting the money of its taxpayers.

End of the Honolulu Rail Line

The city hopes to receive $1.55 billion from the federal government, with local residents left to pay a hefty 70 percent of the cost. This $3.575 billion local share would create the highest tax burden for any urban rail line ever built in the nation, at more than $10,000 per household. But residents should "thank their lucky stars" if that’s all they have to pay, given the history of cost overruns on such projects around the world.

Stacking the Deck: The Federal Court Challenge: The planning process is being challenged in federal court. The plaintiffs argue that the rail selection process eliminated more cost effective options with biased analysis. This would not be the first time.

Annie Weinstock, Walter Hook, Michael Replogle, and Ramon Cruz of the Institute for Transportation Development and Policy (with a foreword by Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenaur), cited circuitous routing of a busway that biased ridership forecasts in favor of light rail for the suburban Washington Purple Line. Weinstock, Hook, Repogle and Cruz refer to a similar "deck stacking technique" that favored an expensive rail project over a busway in the suburban Washington Dulles corridor. They fault local officials more than federal:

While there is no outright pro-rail bias at the FTA, there is indeed FTA complicity in the rail bias of city and state level mass transit project sponsors. The FTA, when evaluating New Starts and Small Starts project applications, tends to bow to political pressure to favor locally preferred alternatives and ignore certain forms of rail bias by the project sponsors

Pulling the Plug on Rail? Former Governor Ben Cayatano has filed to run against Mayor Carlisle in the August 2012 election. In announcing his entry, Governor Cayatano said "I will pull the plug on rail." Polls show Mr. Cayetano ahead of both Mayor Carlisle and a third candidate.

Capital Cost Escalation: A state report indicated that construction costs could rise well above forecast. Every penny above the $5.125 billion capital cost will be the responsibility of local taxpayers. Based upon the international experience, this could easily raise the per household cost from $15,000 to $20,000.

Ridership Optimism Bias: Echoing general concerns raised by Weinstock, Hook, Repogle and Cruz (above), the state report indicated concern over an optimism bias in the ridership projections. For example, the city expects 60 percent of rail riders to use the bus to get to the train. This is four times the rate of the largest new rail system built in the nation (Washington’s Metro). Using the bus to connect to the train makes travel much slower and this factor has often been over-estimated by rail planners. This unrealistic assumption alone could qualify the Honolulu ridership forecast as among the most inaccurate in history. Fewer riders. more money out of residents pockets.

A Billion Here, A Billion There: As if all of this were not enough, a report for the Federal Transit Administration, obtained by the Star Advertiser through a freedom of information request, indicates that the operating costs of the transit system may be understated by as much as $1 billion over the next 20 years. That’s $3,000 per Honolulu household (Note 1).

Federal Doubts: Federal Transit Administration Regional Administrator Leslie Rogers expressed concern about Honolulu’s ability to afford the project in a letter to local officials, noting that the funding program is insufficient. Local taxpayers likely will need to pony up more.

Debt Limit Suspended: After having claimed it could afford the rail debt, the city suspended its debt limit — a fact discovered four months after the fact by the Star Advertiser. Usually, breaches of trust like this become evident only much later in the rail construction process. A suspended debt limit means more money out of taxpayer pockets, or worse. Jefferson County, Alabama filed bankruptcy after not being able to afford payments on its sewer debt.

How Would Rail Change Honolulu

With rail, Honolulu there are two ways that Honolulu will be changed:

What Will Change: Walling Off the Waterfront. The elevated design of the rail system is so intrusive that the local chapter of the American Association of Architects opposes the proposal. The elevated line would run directly in front of the waterfront. Its oppressive design would separate the rest of the historic Aloha Tower area from the rest of the city and could preclude future attractive "placemaking" development (see lead photo, courtesy of the Honolulu Chapter of the American Institute of Architects).

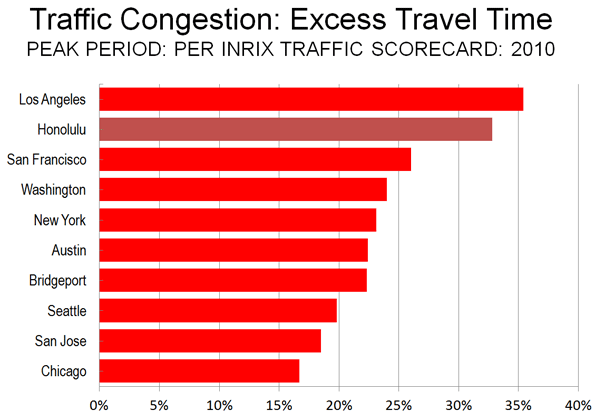

No Traffic Relief: Despite being only the 52nd largest metropolitan area in the nation, Honolulu has the second worst traffic congestion in the nation (see figure), according to INRIX, the leading international reporting source. Honolulu and Los Angeles are the only US metropolitan areas ranked in the worst 25 out of 200 in Western Europe and the United States. Even with the rail system, local plans call for traffic congestion to get worse.

Getting the Choices Right

Incumbent Mayor Peter Carlisle recently returned from a Potemkin Village tour of Manila, raving about that city’s rail system. Governor Cayateno, whose familiarity with Manila extends well beyond a scripted tour, called Mayor Carlisle’s comparison with Manila "comedic," noting that most residents cannot afford a car or that Manila has more than 10 times as many people.

Manila Rail System: Part the Mayor Did not See

The mayor may not have been aware that more than 4,000,000 – more than one-third – of Manila’s (National Capital Region) residents live in slums, shantytowns and informal settlements, where sewers are rare if not non-existent. Government projections indicate that the slum population will rise to 9,000,000 by 2050. More than one-half of Manila’s population will be in slums.

Manila Slum

In his recent "state of the city’" address, Mayor Carlisle mused "Manila without rail transit would be unthinkable." That may be the view of an itinerate visitor, but not of the majority who never ride it. For millions, a Manila with sewers is unimaginable. First world urban areas all have sewers. But many do not have rail systems. Honolulu could use some genuine prioritization and less contempt for the hard earned income of its residents.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

—–

Note 1: Illinois Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, who was minority leader of the United States Senate in the 1960s is reported to have said: "A million here, a million there, pretty soon, you’re talking real money." The line has been often repeated, though the rise in government spending is indicated by the inflation from "millions" to "billions."

Note 2: Manila’s rail system serves a very small market and represents a small share of transit ridership. The latest available data suggested that barely five percent of transit ridership was on rail.

Top Photo: Visual of rail system in downtown Honolulu (courtesy of American Institute of Architects, Honolulu Chapter)

Photo credits: All others by author