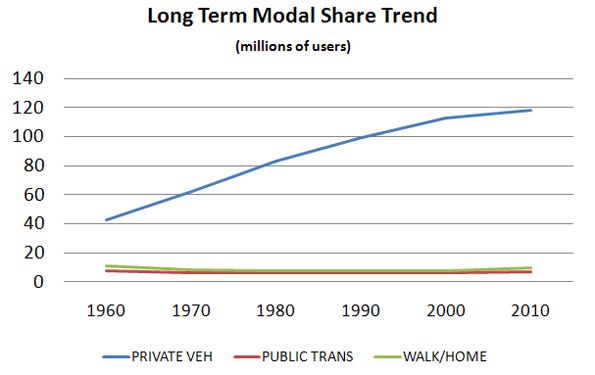

As we indicated in the last article, solo automobile commuting reached an all time record in the United States in 2010, increasing by 7.8 million commuters. At the same time, huge losses were sustained by carpooling, while the largest gain was in working at home, which includes telecommuting. Transit and bicycling also added commuters. This continues many of the basic trends toward more personalized employment access that we have seen since 1960.

Solo Automobile Commuting: Among the nation’s 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1 million population, 38 experienced increases in solo automobile commuting between 2000 and 2010. More than 80% of commuting is by solo automobile in 25 of the 51 largest metropolitan areas, with the highest rates being in Birmingham, Detroit, Cincinnati, Indianapolis and Kansas City. Another 28 metropolitan areas have single automobile commute shares of between 70% and 80%, with Boston, Washington and San Francisco between 60% and 70%. As would be expected, the lowest solo automobile commute share was in New York at 51%.

Car Pools: The national data also showed a nearly 2.4 million loss in carpool use. The losses were pervasive, occurring in all 51 metropolitan areas. Riverside-San Bernardino had the highest carpool market share at just under 15%, while all other major metropolitan areas were below 12%. Car pools have been losing market share for decades.

Work at Home (Includes Telecommuting): In what we have previously labeled as The Decade of the Telecommute, the nation experienced a 1.7 million increase in working at home over the past decade. The market share gains in working at home were as pervasive as the losses in carpooling, with all 51 metropolitan areas registering increases. Austin had the strongest work-at-home market share, at 7.3%, followed by Portland at 6.5%, San Francisco and Denver at 6.2%, Phoenix at 6.0%, with San Diego, Raleigh and Atlanta above 5.5%. Overall, working at home exceeded transit commuting in 37 major metropolitan areas out of 51 in 2010, up from 27 in 2000. Three metropolitan areas had work at home market shares of less than 3%, including Memphis, New Orleans and last place Buffalo.

Transit: As noted before, transit enjoyed its first 10 year gain since journey to work data was first collected by the Census Bureau 50 years ago. Overall, transit added 900,000 daily commuters, roughly half that for telecommuters. Transit’s market share increased in 25 of the top 51 metropolitan areas. It is also notable that in a number of the metropolitan areas with the largest expenditures for new rail systems, there were either losses or commuting gains were concentrated in the more flexible bus services.

New York: As so often has been the case, transit was largely a "New York story." More than one half of the new transit commuters were in the New York metropolitan area, more than 450,000 of the 900,000 increase. New York boasts by far the most extensive transit system in the nation, which serves the second largest central business district in the world and by far the nation’s most important. In 2000, New York had a transit work trip market share of 27.4%. By 2010, New York’s transit work trip market share had risen to 30.7%, more than double that of any other metropolitan area. More than 70% of the new transit commuters in the New York area were on its subway (Metro), suburban rail and light rail systems.

San Francisco: San Francisco retained its position as the second strongest transit metropolitan area, with a 14.6% work trip market share in 2010. This is up from 13.8% in 2000.

Washington: Washington was the third strongest transit commuting market, with a 14.0% work trip market share in 2010. This modest increase from 13.4% nonetheless produced the second largest ridership increase in the nation, at more than 130,000. This reflects the strength of Washington’s job market over the decade. Rail ridership accounted for 53% of this increase, while buses accounted for the other 47%.

Boston and Chicago: Boston passed Chicago to become the fourth strongest transit market, at 11.8% in 2010. This is an increase from 11.2% in 2000. Chicago ranked fifth at 11.2%, a small reduction from the 11.3% in 2000.

Los Angeles: Los Angeles had the third largest increase in transit commuting, adding 60,000 daily transit commuters. Approximately 75% of these new commuters were attracted by the region’s extensive bus system as opposed to its very expensive but limited rail system. This increase placed Los Angeles in a virtual tie with Portland, with a work trip market share of 6.2%.

Portland: Portland continued to experience its now 30 year transit market share erosion, despite having added three new light rail lines between 2000 and 2010. Portland’s transit work trip market share fell to 6.2% from 6.3% and now trails the work at home and telecommute market share of 6.5%.

Seattle:Seattle added 29,000 new transit commuters for the fourth strongest growth in the nation. Approximately 75% of the new commuters were on the metropolitan area’s bus system.

Atlanta: Atlanta, which is home to the third largest postwar Metro system in the nation (MARTA) gained nearly 9000 new transit commuters, all of them on the bus, while losing more than 3000 rail commuters.

Miami:Miami added 16,000 new transit commuters, though more than 90% were attracted to the bus system, rather than the rail services.

Rail and Bus in Texas: Other metropolitan areas with new and expanded rail systems did not fare as well. In Dallas-Fort Worth, the light rail system was more than doubled in length, yet there was a reduction of more than 3000 daily transit commuters. The transit work trip market share in Dallas-Fort Worth dropped from 1.8% to 1.4%, approximately one quarter lower than that of any other major metropolitan area with a new light rail or Metro system. Houston, which built its first light rail line during the period, lost nearly 3000 daily transit commuters, with its transit work trip market share dropping by nearly one-third, from 3.2% to 2.3%. By contrast, the third largest metropolitan area in Texas, San Antonio, lost no commuters from its bus only transit system.

Other New Rail Metropolitan Areas: Other metropolitan areas with new rail systems experienced modest ridership increases, with 60 to 70 percent of the increase on the bus systems in Charlotte, Minneapolis-St. Paul and Phoenix. Salt Lake City experienced a small decline in transit commuting.

Below 1 Percent: Four metropolitan areas had transit work trip market shares of less than 1%, including Indianapolis, Raleigh, Birmingham and last place Oklahoma City, with a market share of 0.4%.

Bicycles: It was also a good decade for bicycle commuting, with the national increase of nearly 250,000. The bicycle commuting market share rose in 45 of the 51 largest metropolitan areas. Portland had the highest bicycle market share at 2.2%, with three other metropolitan areas at 1.5% or above, Sacramento, San Francisco and San Jose. The lowest bicycle commuting market shares were in San Antonio, Cincinnati, Birmingham and Memphis, all at 0.1 percent.

Walking: There was little change in walking among the nations major metropolitan areas. The largest shares were in New York (5.9%) and Boston (5.4%), with the smallest shares in Raleigh (1.1%), Orlando (1.1%) and Birmingham (1.0%).

Drifting Away from Shared Commuting: In some ways, the 2000s were different than previous decades, especially with the reversals in bicycle commuting and transit. However, overall, shared ride commuting (transit and car pools) lost share due to the precipitous decline in car pooling. Longer term share increase trends also continued in single-occupant automobile commuting and working at home. The bottom line: personal employment access (personal mobility plus working at home) continues to carve away at the smallish share still held by shared commuting.

————-

Data: The 2000 and 2010 commuting market shares by mode are shown in Tables 1 and 2 (2010 metropolitan area boundaries).

————

| Table 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Work Trip Market Share: 2000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Metropolitan Areas Over 1,000,000 Population in 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Metropolitan Area |

Car, Truck or Van: Alone |

Car/Van Pool |

Transit |

Bicycle |

Walk |

Other |

Work at Home (Includes Telecommute) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Atlanta |

77.0% |

13.7% |

3.4% |

0.1% |

1.3% |

1.1% |

3.5% |

| Austin |

76.5% |

13.7% |

2.5% |

0.6% |

2.1% |

1.1% |

3.6% |

| Baltimore |

75.5% |

11.5% |

5.9% |

0.2% |

2.9% |

0.9% |

3.2% |

| Birmingham |

83.3% |

12.0% |

0.7% |

0.1% |

1.2% |

0.7% |

2.1% |

| Boston |

71.1% |

8.6% |

11.2% |

0.5% |

4.6% |

0.8% |

3.3% |

| Buffalo |

81.7% |

9.4% |

3.3% |

0.2% |

2.7% |

0.5% |

2.1% |

| Charlotte |

80.7% |

12.8% |

1.4% |

0.1% |

1.2% |

0.8% |

2.9% |

| Chicago |

70.4% |

11.0% |

11.3% |

0.3% |

3.1% |

1.0% |

2.9% |

| Cincinnati |

81.3% |

10.1% |

2.8% |

0.1% |

2.3% |

0.6% |

2.7% |

| Cleveland |

81.3% |

8.8% |

4.1% |

0.2% |

2.2% |

0.6% |

2.7% |

| Columbus |

82.1% |

9.7% |

2.1% |

0.2% |

2.3% |

0.6% |

3.0% |

| Dallas-Fort Worth |

78.7% |

13.9% |

1.8% |

0.1% |

1.5% |

1.0% |

3.0% |

| Denver |

76.0% |

11.7% |

4.4% |

0.4% |

2.1% |

0.8% |

4.6% |

| Detroit |

84.7% |

9.2% |

1.7% |

0.1% |

1.4% |

0.6% |

2.2% |

| Hartford |

82.6% |

8.7% |

2.8% |

0.2% |

2.5% |

0.6% |

2.6% |

| Houston |

77.0% |

14.3% |

3.2% |

0.3% |

1.6% |

1.1% |

2.5% |

| Indianapolis |

82.8% |

10.4% |

1.3% |

0.2% |

1.7% |

0.7% |

3.0% |

| Jacksonville |

80.3% |

12.6% |

1.3% |

0.5% |

1.7% |

1.4% |

2.3% |

| Kansas City |

82.6% |

10.6% |

1.2% |

0.1% |

1.4% |

0.7% |

3.5% |

| Las Vegas |

74.6% |

14.7% |

4.4% |

0.5% |

2.3% |

1.3% |

2.3% |

| Los Angeles |

71.9% |

14.6% |

5.6% |

0.7% |

2.7% |

1.0% |

3.5% |

| Louisville |

81.8% |

11.2% |

2.0% |

0.2% |

1.7% |

0.7% |

2.5% |

| Memphis |

80.7% |

13.3% |

1.6% |

0.1% |

1.3% |

0.9% |

2.2% |

| Miami-West Palm Beach |

77.3% |

13.1% |

3.2% |

0.5% |

1.7% |

1.2% |

3.1% |

| Milwaukee |

79.7% |

9.9% |

4.2% |

0.2% |

2.9% |

0.6% |

2.6% |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul |

78.3% |

10.0% |

4.4% |

0.4% |

2.4% |

0.6% |

3.8% |

| Nashville |

80.5% |

13.1% |

0.8% |

0.1% |

1.5% |

0.8% |

3.2% |

| New Orleans |

72.9% |

14.6% |

5.4% |

0.6% |

2.7% |

1.3% |

2.4% |

| New York |

52.7% |

9.3% |

27.4% |

0.3% |

6.0% |

1.5% |

2.9% |

| Oklahoma City |

81.6% |

12.1% |

0.5% |

0.2% |

1.7% |

1.0% |

2.9% |

| Orlando |

80.6% |

12.1% |

1.6% |

0.4% |

1.3% |

1.1% |

2.9% |

| Philadelphia |

73.1% |

10.2% |

8.9% |

0.3% |

3.9% |

0.7% |

2.9% |

| Phoenix |

74.6% |

15.3% |

1.9% |

0.9% |

2.1% |

1.4% |

3.7% |

| Pittsburgh |

77.5% |

9.8% |

5.9% |

0.1% |

3.6% |

0.6% |

2.5% |

| Portland |

73.1% |

11.5% |

6.3% |

0.8% |

2.9% |

0.8% |

4.6% |

| Providence |

80.7% |

10.5% |

2.4% |

0.2% |

3.3% |

0.8% |

2.2% |

| Raleigh |

80.8% |

12.1% |

0.9% |

0.2% |

1.6% |

1.0% |

3.5% |

| Richmond |

81.7% |

10.9% |

1.9% |

0.2% |

1.8% |

0.8% |

2.7% |

| Riverside-San Bernardino |

73.5% |

17.6% |

1.6% |

0.5% |

2.2% |

1.2% |

3.5% |

| Rochester |

81.7% |

9.1% |

2.0% |

0.2% |

3.5% |

0.6% |

2.9% |

| Sacramento |

75.3% |

13.5% |

2.7% |

1.4% |

2.2% |

0.9% |

4.0% |

| Salt Lake City |

76.0% |

13.4% |

3.3% |

0.5% |

2.1% |

0.7% |

4.0% |

| San Antonio |

76.2% |

14.9% |

2.7% |

0.1% |

2.4% |

1.2% |

2.6% |

| San Diego |

73.9% |

13.0% |

3.3% |

0.6% |

3.4% |

1.4% |

4.4% |

| San Francisco-Oakland |

62.8% |

12.7% |

13.8% |

1.1% |

3.9% |

1.3% |

4.3% |

| San Jose |

77.2% |

12.4% |

3.4% |

1.2% |

1.8% |

0.9% |

3.1% |

| Seattle |

71.6% |

12.7% |

7.0% |

0.6% |

3.1% |

0.8% |

4.2% |

| St. Louis |

82.5% |

10.0% |

2.2% |

0.1% |

1.7% |

0.6% |

2.9% |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg |

79.7% |

12.4% |

1.3% |

0.6% |

1.7% |

1.2% |

3.1% |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk |

78.8% |

12.1% |

1.7% |

0.3% |

2.7% |

1.6% |

2.7% |

| Washington |

67.5% |

13.4% |

11.2% |

0.3% |

3.0% |

0.9% |

3.7% |

| Top 51 Metropolitan Areas |

73.2% |

11.8% |

7.5% |

0.4% |

2.9% |

1.0% |

3.2% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calculated from Census Bureau data |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Metropolitan areas as defined in 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Work Trip Market Share: 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Metropolitan Areas Over 1,000,000 Population in 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Car, Truck or Van: Alone |

Car/Van Pool |

Transit |

Bicycle |

Walk |

Other |

Work at Home (Includes Telecommute) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Atlanta |

77.6% |

10.3% |

3.4% |

0.2% |

1.3% |

1.5% |

5.8% |

| Austin |

75.6% |

10.5% |

2.3% |

0.6% |

1.9% |

1.8% |

7.3% |

| Baltimore |

76.5% |

9.6% |

6.0% |

0.2% |

2.6% |

1.0% |

4.1% |

| Birmingham |

84.8% |

10.0% |

0.6% |

0.1% |

1.0% |

0.5% |

3.1% |

| Boston |

69.5% |

7.5% |

11.8% |

0.7% |

5.4% |

0.8% |

4.4% |

| Buffalo |

82.0% |

7.5% |

3.8% |

0.3% |

3.0% |

1.1% |

2.3% |

| Charlotte |

80.6% |

10.0% |

2.0% |

0.2% |

1.5% |

0.6% |

5.1% |

| Chicago |

71.0% |

8.5% |

11.2% |

0.6% |

3.1% |

1.0% |

4.5% |

| Cincinnati |

84.1% |

7.9% |

2.1% |

0.1% |

2.0% |

0.4% |

3.4% |

| Cleveland |

82.3% |

7.2% |

3.6% |

0.3% |

2.2% |

0.7% |

3.7% |

| Columbus |

82.4% |

8.0% |

1.7% |

0.5% |

2.3% |

0.6% |

4.6% |

| Dallas-Fort Worth |

81.3% |

10.1% |

1.4% |

0.2% |

1.2% |

1.4% |

4.6% |

| Denver |

76.3% |

9.6% |

4.1% |

0.8% |

1.9% |

1.1% |

6.2% |

| Detroit |

84.6% |

8.5% |

1.5% |

0.2% |

1.4% |

0.8% |

3.0% |

| Hartford |

81.5% |

7.9% |

3.1% |

0.3% |

3.0% |

1.0% |

3.2% |

| Houston |

79.4% |

11.5% |

2.3% |

0.3% |

1.4% |

1.7% |

3.4% |

| Indianapolis |

83.9% |

8.2% |

0.9% |

0.3% |

1.5% |

0.8% |

4.3% |

| Jacksonville |

82.5% |

8.9% |

1.0% |

0.5% |

1.4% |

1.2% |

4.5% |

| Kansas City |

83.7% |

8.5% |

1.2% |

0.2% |

1.4% |

0.9% |

4.1% |

| Las Vegas |

78.9% |

10.5% |

3.8% |

0.6% |

1.6% |

1.3% |

3.3% |

| Los Angeles |

73.5% |

10.7% |

6.2% |

0.9% |

2.6% |

1.2% |

5.0% |

| Louisville |

83.5% |

9.2% |

1.9% |

0.2% |

1.3% |

0.9% |

3.1% |

| Memphis |

83.6% |

10.3% |

1.0% |

0.1% |

1.5% |

0.9% |

2.7% |

| Miami-West Palm Beach |

78.8% |

9.4% |

3.5% |

0.6% |

2.0% |

1.4% |

4.4% |

| Milwaukee |

80.1% |

9.3% |

3.4% |

0.5% |

2.6% |

0.7% |

3.4% |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul |

78.3% |

7.9% |

4.8% |

0.7% |

2.4% |

0.9% |

4.9% |

| Nashville |

81.3% |

10.7% |

1.0% |

0.2% |

1.2% |

1.0% |

4.6% |

| New Orleans |

78.1% |

11.0% |

3.2% |

0.7% |

2.6% |

1.9% |

2.5% |

| New York |

50.5% |

6.8% |

30.7% |

0.5% |

5.9% |

1.6% |

3.9% |

| Oklahoma City |

82.7% |

10.6% |

0.5% |

0.3% |

1.6% |

1.0% |

3.4% |

| Orlando |

82.1% |

9.2% |

1.6% |

0.3% |

1.1% |

1.4% |

4.4% |

| Philadelphia |

73.9% |

8.0% |

9.6% |

0.5% |

3.5% |

0.8% |

3.8% |

| Phoenix |

76.7% |

11.8% |

2.0% |

0.6% |

1.5% |

1.5% |

6.0% |

| Pittsburgh |

77.0% |

8.9% |

5.6% |

0.3% |

3.7% |

0.9% |

3.5% |

| Portland |

72.1% |

8.8% |

6.2% |

2.2% |

3.3% |

0.9% |

6.5% |

| Providence |

81.3% |

8.3% |

2.6% |

0.5% |

3.2% |

0.9% |

3.2% |

| Raleigh |

82.0% |

8.7% |

0.9% |

0.3% |

1.1% |

1.1% |

5.9% |

| Richmond |

81.2% |

10.1% |

1.8% |

0.4% |

1.2% |

0.7% |

4.6% |

| Riverside-San Bernardino |

76.1% |

14.8% |

1.7% |

0.4% |

1.8% |

1.4% |

3.8% |

| Rochester |

82.6% |

7.1% |

1.8% |

0.4% |

3.9% |

0.7% |

3.6% |

| Sacramento |

75.6% |

11.2% |

2.9% |

1.7% |

1.9% |

1.1% |

5.5% |

| Salt Lake City |

77.7% |

11.3% |

2.9% |

0.8% |

2.3% |

1.0% |

4.0% |

| San Antonio |

79.5% |

11.5% |

2.1% |

0.1% |

2.0% |

1.4% |

3.3% |

| San Diego |

76.2% |

10.1% |

3.3% |

0.8% |

2.8% |

1.0% |

5.9% |

| San Francisco-Oakland |

61.5% |

10.6% |

14.6% |

1.7% |

4.2% |

1.2% |

6.2% |

| San Jose |

77.5% |

10.3% |

2.9% |

1.6% |

1.8% |

0.9% |

5.1% |

| Seattle |

70.5% |

10.2% |

8.2% |

1.1% |

3.5% |

1.0% |

5.5% |

| St. Louis |

83.0% |

7.7% |

2.6% |

0.2% |

1.9% |

0.8% |

3.7% |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg |

80.3% |

9.5% |

1.6% |

0.8% |

1.4% |

1.4% |

5.0% |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk |

80.9% |

9.4% |

1.8% |

0.5% |

3.3% |

0.9% |

3.1% |

| Washington |

65.6% |

10.6% |

14.0% |

0.5% |

3.5% |

1.0% |

4.9% |

| Top 51 Metropolitan Areas |

73.7% |

9.4% |

7.9% |

0.6% |

2.8% |

1.2% |

4.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Calculated from Census Bureau data |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Metropolitan areas as defined in 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photo: Manhattan (New York), with the Woolworth Building in the distance (by author)