California’s high-speed rail project is setting speed records, not on tracks, but rather in cost escalation. Last week, the California High Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) announced that the Bakersfield to Merced section, part of which will comprise the first part of the system to be built, will cost between $10.0 and $13.9 billion. This is an increase of approximately 40 percent to 100 percent over the previous estimate of $7.1 billion, an estimate itself less than two years old.

This "flatter than Kansas" section should be the least expensive part of the system. It can only be imagined how much costs might rise where construction is more challenging, such as tunneling through the Tehachapi Mountains and for the route across the environmentally sensitive Pacheco Pass that leads to the Silicon Valley. CHSRA officials admit that the present $43 billion cost estimate to complete the Los Angeles (Anaheim) to San Francisco first phase will rise substantially. This estimate was also less than two years old.

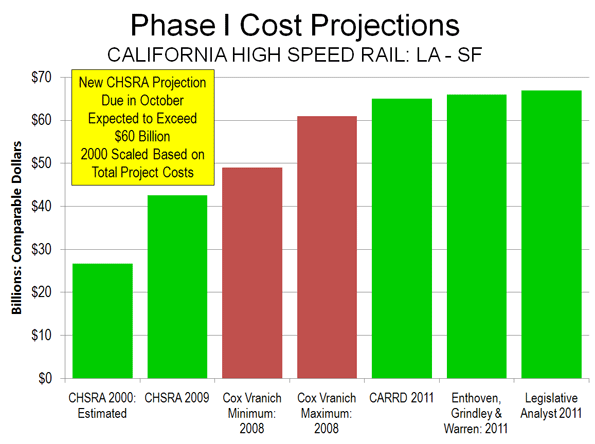

Today only the most ardent supporters believed that initial estimate figure any longer. Early in the year, CARRD (Californians Advocating Responsible Rail Design) looked closely at CHSRA documentation and estimated that Phase I would instead cost $65 billion. In May, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office indicated that based upon the cost escalation already taking place, the cost of Phase I could reach $67 billion. Alain Enthoven of Stanford University, William Grindley, formerly of the World Bank and William Warren, a former Silicon Valley CEO project a $66 billion figure (see Figure) and also estimate that costs for the complete project, with extensions to San Diego and Sacramento could be up to $116 billion (Note 1). This is triple the 2000 CHSRA projection (inflation adjusted).

Megan McArdle of The Atlantic characterized the obsolete $43 billion estimate as "giddily optimistic," while Reihan Salam of National Review Online called the cost escalation "a national embarrassment." In fact, even the $43 billion represented substantial cost escalation. Over the previous decade, the project cost had escalated more than 50 percent after adjustment for inflation.

Any one of the new cost projection figures would put the California High Speed Rail project on track for a world high speed record in cost escalation. Available data indicates that no transportation infrastructure project in the history of the world has experienced such a large cost increase in so little time.

Cox/Vranich Projection Low: In 2008, Joseph Vranich and I authored the Reason Foundation’s The California High Speed Rail Proposal: A Due – Diligence Report. Based upon the cost escalation we predicted in that report, our cost escalation estimate for Phase I would have been between $49 billion and $61 billion (Note 2). Little did we expect that our maximum cost escalation figure would turn out to be too conservative and be exceeded even before the first shovel had been turned.

Rippling to Florida: There has already been a ripple effect from California’s record cost escalation. My Reason Foundation report on the Florida high speed rail project (The Tampa to Orlando High Speed Rail Project: A Florida Taxpayer Assessment) used a comparison to the first segment of the California system to produce a maximum cost overrun estimate of $3 billion for the Florida system. Had the new cost estimates been available at the time, we would have projected even higher cost overruns. Of course, Governor Rick Scott canceled that project to shield the taxpayers of the state from obligations not only for cost overruns but also for operating subsidies.

Citizen Opposition: Meanwhile, the California project has encountered other difficulties. Strong community opposition to the project has developed along the route through the generally Democratic voting peninsula cities between San Jose and San Francisco. CHSRA had intended to expand the existing commuter rail and freight rail right-of-way from 2 to 4 tracks either elevated or to put it in a trench. Residents fear that an elevated system would be a virtual "Berlin Wall" dividing their communities and that a trench would be little better. Vigorous opposition has also developed in the Central Valley (San Joaquin Valley), which is one of the world’s leading agricultural areas.

There is also a dispute on routing, as CHSRA considers crossing the "Grapevine" parallel to Interstate 5 between Los Angeles and Bakersfield, rather than the adopted, longer route through the Antelope Valley (the Lancaster-Palmdale urban area, which is likely to have 500,000 people by 2020 when the train is supposed to begin operating).

Slowing Down the Trains: The peninsula residents have been successful in obtaining strong political support in Sacramento and Washington. There are indications that a "blended" alternative might be developed instead of the elevated or trench alternatives. This would involve mixing high-speed trains on the same two tracks is the present Cal Train commuter service. Of course, this means that the high speed trains could not run very fast. This could add up to 50 minutes to the schedule between Los Angeles and San Francisco, which would make it impossible for the trains to reach the travel time mandated in state law of 2:40. Instead, the trains could take up to 3:30.

Our Due Diligence Report expressed doubts about the ability of CHSRA to deliver on the legislatively mandated travel times. We predicted that the fastest non-stop trains would take 3:41 between Los Angeles and San Francisco, not much more than the 3:30 that could result from the "blended" alternative. Even that time might not be achievable should citizen opposition develop along other parts of the line. California would, as a result, get the look, but not the substance of high speed rail.

A Shortage of Funding: Perhaps the final blow will come from financial reality, a commodity often in short supply in recent California history. At this point, the project has received less than $4 billion in federal grants, which together with a matching $4 billion from the state bonds authorized by taxpayers could be spent. However, given the Republican control of the House of Representatives and the tight federal budget, the prospect for additional federal funding seems dim. High-speed rail was deleted from the federal budget in the agreement between Congress and the President in April. The 2012 budget passed by the House of Representatives does not contain money for high-speed rail.

CHSRA is optimistic about receiving private investment to fund a major part of the construction. Although there is no shortage of companies looking to be paid to do work on the high-speed rail project, the room empties out when firms are asked to risk billions of their own capital on the project. CHSRA’s own documents indicate that investors are likely to require revenue guarantees, which would appear to violate provisions of the state law that placed the bond issue on the ballot in 2008.

The Prospects: At this point there seem to be three potential outcomes. The first, and least likely, is that CHSRA will obtain sufficient funding to build Phase I. Alternatively, CHSRA could build only some portion of the line in the Central Valley, and high speed rail would likely not operate in this far less densely traveled corridor. This would leave California with the most extravagant Amtrak segment in the nation. The third potential outcome is, of course, that the system will never be built.

Bipartisan concerns are now being expressed in Sacramento, where some Democrats worry that high-speed rail could divert money from more critical, and politically influential, uses. Senator Alan Lowenthal (D-Long Beach), who chairs a committee overseeing the project may have spoken for many after the events of the week: "This is really very serious and needs to stop in its tracks. We can’t just be acting as if someone’s out there giving us wheelbarrows full of money, and it’s just coming. This is not the way we should be operating."

—-

Note 1: Enthoven, Grindley and Warren also note that if the California high speed rail project were to equal the worst level of cost escalation yet in California (the San Francisco Bay Bridge project, which is now underway), the costs would rise to as much as $213 billion (Cited in The Wall Street Journal editorial, "Runaway Trains").

Note 2: Our estimates have been adjusted to "year-of-expenditure" dollars, the method currently used by CHSRA in its cost estimates.

Photo: California’s Central Valley (where first segment is to be built)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”