State governments have to stop treating transportation like yet another welfare program.

Among urban and rural areas, who subsidizes whom?

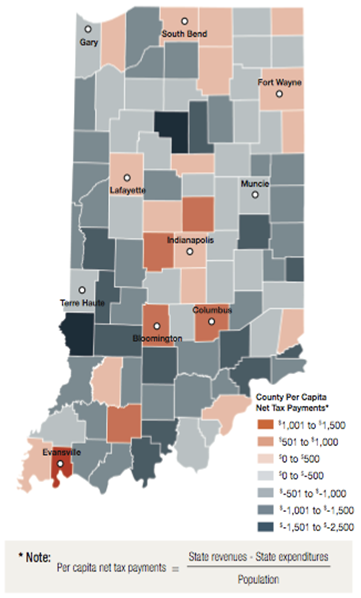

It’s methodologically difficult to measure net taxation, but the studies that have been done suggest that, contrary to the belief of some, urban areas are big time net tax donors. For example, a recent Indiana Fiscal Policy Institute study found that Indiana’s urban and suburban counties generally subsidize rural ones.

Just the consolidated city-county of Indianapolis-Marion County sends $420 million more to the state annually than it receives every year. That’s equal to the entire public safety budget of the city. The rest of the metro area sends another $340 million to the state annually.

Similarly, a 2009 Georgia State University study found that the Atlanta metro area accounted for 61% of state tax collections but only but only 47% of expenditures. A 2004 University of Louisville study found that the state’s three major urban regions – Louisville, Lexington, and Northern Kentucky (south suburban Cincinnati) – generate over half the state’s tax revenues but only receive back about one third in state expenditures, an annual net outflow of $1.4 billion per year.

The Atlanta and Indianapolis examples are particularly instructive, since both are the capital and by far the largest city of their state. They are sometimes presumed to benefit from disproportionate state spending as a result, but the reality is quite different.

That’s not to say that this is necessarily bad. The fundamental basis of any government is a commonwealth, a body of citizens who see themselves as fellows, who believe each other’s fates are linked. Thus, generally spreading the burdens on some type of a progressive basis is broadly considered equitable, and assistance to the less fortunate constitutes a core function of government. To the extent that cities generate the most wealth in today’s economy, and have the highest incomes, it is no surprise they pay more in taxes. This doesn’t per se mean there’s an anti-urban bias in policy.

Indeed, income redistribution is one of the key functions of state government. Actual welfare and safety net programs, including things like health care for the poor, are a major budget item in every state. But it goes beyond that. K-12 education could be treated as a purely local service, but every state spends large amounts on it. One could argue this is strictly to ensure a minimum level of funding equity between rich and poor districts. That is, it’s purely redistributive. Indeed, states sadly spend more time fiddling with funding formulas than in actual education reform and improvement. Even corrections disproportionately and unfortunately affects the poor. We are, in effect, a collection of 50 welfare states.

The fact that so many of the functions of state government have taken on a redistributive cast also comes with downsides. Most importantly, even functions that should have little to do with welfare or equity have come to be seen through that lens.

Exhibit A is transportation. Two-thirds of Americans live in large metro areas, yet less than half the federal transportation stimulus funds are going to the top 100 metro areas. Missouri is spending half its stimulus money on 89 small counties that account for only a quarter of the state’s population. In Ohio, the state cancelled plans to spend $100 million in stimulus funds on the crumbling Cleveland Inner Belt bridge in order to divert them to paying for a $150 million bypass around Nelsonville – a town of only 5,000 people. This is part of a plan to construct a four lane divided highway into sparsely populated southeast Ohio as part of a “build it and they will come” economic development plan. Mecklenburg County, NC, the state’s largest and home to Charlotte, received only $7.8 million out of the first $423 million in projects in that state. The Atlantic Monthly described this as a contest between a “mayor’s stimulus” and a “governor’s stimulus” – and the governor won.

State after state has rural “roads to nowhere.” Without any legitimate economic development strategy on offer for depressed rural areas and small industrial cities, salvation is said to lie in access to four lane highways. The logic is that until every county in America is crisscrossed with these things, somehow residents are deprived of their due. This plays well to rural resentment, allowing people who are by nature proud believers in self-reliance and dismissive of welfare to claim instead that they’ve been cheated out of their “fair share” of transportation money. One suspects at least some deep inside understand the fiscal reality, which accounts for the self-righteous rhetoric designed as much perhaps to convince themselves as others.

Regardless, a lack of transportation investment is crippling our cities, many of which have congested, crumbling roads and shaky bridges. Earmark reform would help at the federal level. Earmarked projects and “high priority corridors” are too often, as with “strategic” corporate programs, projects for which no traditional justification can be found.

But beyond this, governance reform at the state level is critical to bring transportation funding allocations in line with real population and economic development measures. That’s not to say that rural areas should get no funding. There are many areas where legitimate state funding is warranted, such as replacing substandard bridges or correcting roads with dangerous geometry. But that doesn’t mean states should spend huge amounts of money on large rural expansion projects of dubious value that rob urban areas of the funds needed for projects with genuine transportation merit and real economic development potential.

If states won’t act to reform this, then, despite legitimate governance concerns in our system of federalism, the federal government may need to step in to take a more direct role in funding formulas to ensure that a proper share of the money gets sub-allocated to metro areas. The federal government simply can’t allow states to continue diverting critical and limited transport money to boondoggles.

With metro areas as the economic locus of the 21st century, failing to take action to make sure our cities get the transportation investment they need puts both the state treasury and national economic competitiveness at risk. Cities can only continue to play their role as wealth generators and sources of transfer funds for their states if they themselves are economically healthy, which requires infrastructure investment. As the Indiana, Georgia, and Kentucky examples show, state treasuries and rural funding are dependent on urban economic health. You can’t redistribute money from urban to rural areas if there’s nothing to distribute.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs based in the Midwest. His writings appear at The Urbanophile.

Photo: Pete Zarria

This is not to discount the traffic and other difficulties. However, the Chinese, like their western counterparts, will continue to seek better lives and that means greater personal mobility. It means that E-Bike usage will continue to grow and that car usage will also continue to grow, as incomes rise. While that will make traffic congestion even worse, the spectacular automobile fuel efficiency improvements ahead will allow massive expansion of personal mobility, while moving in the right direction with respect to the carbon footprint. In the final analysis, the Chinese (and the Indians, Indonesians, etc.) would like to live as well as we do in the United States and Western Europe. And why not?

This is not to discount the traffic and other difficulties. However, the Chinese, like their western counterparts, will continue to seek better lives and that means greater personal mobility. It means that E-Bike usage will continue to grow and that car usage will also continue to grow, as incomes rise. While that will make traffic congestion even worse, the spectacular automobile fuel efficiency improvements ahead will allow massive expansion of personal mobility, while moving in the right direction with respect to the carbon footprint. In the final analysis, the Chinese (and the Indians, Indonesians, etc.) would like to live as well as we do in the United States and Western Europe. And why not?