There is no better way to see China than by train. This is especially true because foreigners are not allowed to drive rental cars without first obtaining a Chinese drivers license. China has developed the world’s largest high-speed rail system, which includes one of only three profitable routes in the world, along with Tokyo to Osaka and Paris to Lyon.

Travel by train in China is now more convenient for people who do not speak Mandarin. Tickets may now be purchased over the internet. Details of the trains and ticketing are provided at the end of the article.

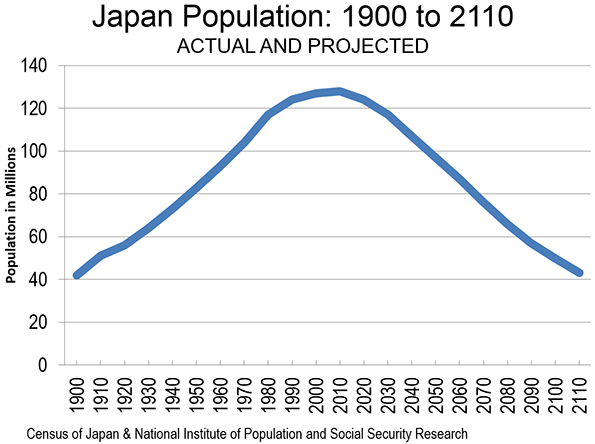

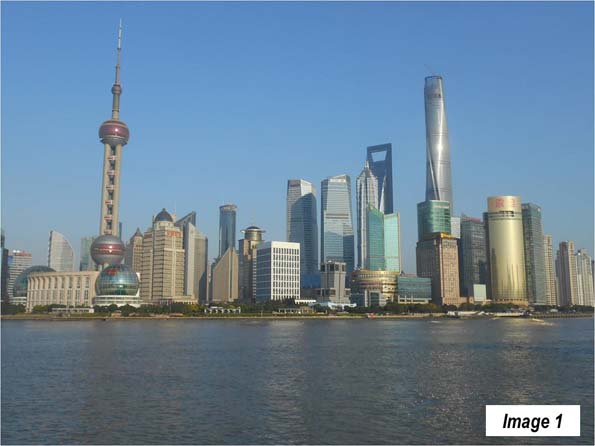

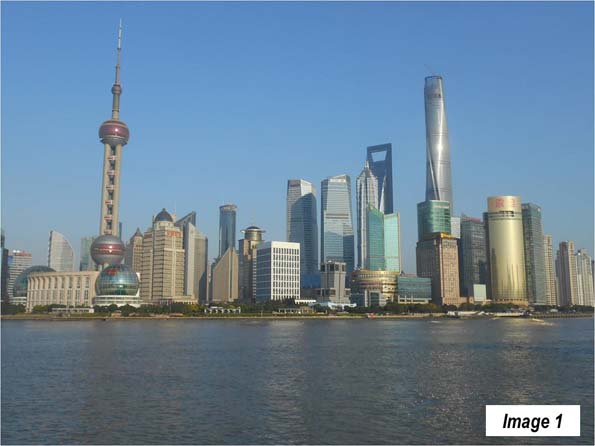

Last month I traveled from Shanghai (Image 1 from a previous trip) to Changchun and Jilin, in Manchuria’s Jilin Province (Manchuria includes the northeastern provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heliongjiang, and is called the "Dong Bei" or the "east north") and then to Beijing and on to Nanchang, in Jiangxi Province, finally returning to Shanghai.

Shanghai is China’s largest urban area, with 22.7 million residents (Note). I started out from Shanghai’s Hongqiao Railway Station, which is one of the most important rail hubs in the country. It is located across the runways from Hongqiao International Airport, from which most domestic flights operate. Most international flights operate from Pudong International Airport, which is 34 miles (55 kilometers) to the east.

The train used the main Shanghai to Beijing line as far as Tianjin, where the train continues along Bohai Bay toward Manchuria, while the main line turns left toward Beijing.

It is not long before the train reaches speeds above 300 kilometers per hour (186 miles per hour). For at least the first 135 miles (220 kilometers), to the far edge of Changzhou, there is a mix of primarily urban development with some rural development. There are also many high-rise residential developments and "peri-urban" developments, with rural areas transitioning to urbanization.

The train travels west through Kunshan, an urban area of 1.9 million residents, part of Suzhou municipality, which also contains the Suzhou urban area (5.4 million). There are particularly good views of the Grand Canal in Suzhou (Image 2, from a previous visit). The Grand Canal was completed approximately 1,400 years ago and for centuries has provided a means for water transport between Hangzhou, to the south of Shanghai, across the Yangtze River and to Tianjin, near Beijing. It is the longest canal in the world, at 1,100 miles (1,800 kilometers).

From Suzhou, the train continues into Wuxi, an urban area of 3.7 million population (Images 3 and 4). The route continues into Changzhou (urban area population 3.7 million). Finally, is some open country, as the main route travels through a valley to the south of Zhenjiang to Nanjing, an urban area of 6.4 million population, which serves as the capital of Jiangsu. Nanjing was the former capital of China and its streets are lined and cooled in the summer by its "French trees" (Image 5, from a previous visit).

Leaving Nanjing, the train crosses the Yangtze River and travel through largely agricultural country. It passes through the smaller Suzhou (Anhui province) of Nobel Literature Prize winner Pearl S. Buck, and then through Xuzhou, Jiangsu (1.3 million). In Xuzhou, I noted the elevated connections for the new rail line to Zhengzhou (and also saw them in Zhengzhou). Service will begin in September, cutting three hours off the Shanghai to Zhengzhou travel time, and placing historic tourist attraction Xi’an, with its Terracotta Army, within seven hours of Shanghai.

The farmland continues to Jinan (3.9 million), the capital of Shandong province, which largely consists of the peninsula of the same name that forms the southern boundary of Bohai Bay. Just north of Jinan, the train crosses the second of China’s great rivers, the Yellow River (Image 6), which is again crossed north of Zhengzhou (below).

Then there follows the longest stretch of agriculture between Shanghai and Beijing, most of the way to Tianjin (Image 7), an urban area of 11.3 million residents and is now the fastest growing large municipality in China, at more than four percent per year. Soon, we passed through Tangshan (2.4 million) which suffered a disastrous earthquake in 1976 but has been rebuilt (Image 8).

The train continued northward to Shenyang (3.4 million), the capital of Liaoning (Image 9). Finally, the train reached the destination of Changchun Railway Station (Image 10), 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) and 11 hours from Shanghai. Changchun (Image 11) is the capital of Jilin province and has 3.4 million residents.

Changchun is called the "automobile city," because the government placed the first automobile manufacturing plant here in the late 1950s. This was where the Red Flag limousine was built, favorite of government ministers and which carried President Richard Nixon around Beijing in his 1972 visit. My hotel in Ordos had a classic Red Flag on exhibition (Image 12). Now, automobile manufacturing is spread around the country and includes virtually all of the world’s leading brands. Last year, Chinese bought 21.1 million cars, compared to 17.5 million in the United States, both records.

Jilin, an urban area with 1.7 million residents,(Images 13, Jilin Railway Station & 14) is only 45 minutes away by train, separated by picturesque rolling agricultural country from Changchun (Images 15 & 16). The corn looks at least as good in Jilin as it does now in Illinois.

A few days later I took the train from Changchun to Beijing South Railway Station (Image 17) to connect for the flight to Ordos, Inner Mongolia (See: Surprising Ordos: The Evolving Urban Form). Beijing is the nation’s second largest urban area, with 20.4 million residents.

Flying back from Ordos, my next train trip was from Beijing West Railway Station. I could have traveled by subway, but since the view underground is not as good, traveled by taxi. Early Sunday morning, the traffic on the Third Ring Road from my hotel near the CCTV Tower (across town) was horrific.

The next train ride was to Nanchang, along the Beijing to Guangzhou line. This is the other principal north-south route though its traffic appears to be light compared to the Shanghai to Being route. The train traveled (Image 18) toward, Shijiazhuang, an urban area of 3.5 million residents and the capital of Hebei province (Images 19 and 20).

Parts of these first three trips coursed through the planned Jin-Jing-Ji megacity, which will better integrate the urban areas between Beijing, Tangshan, Tianjin and Shijiazhuang.

Continuing south, the train stopped at Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan (5.8 million), with its impressive extension of the Zhengzhou new area and the new railway station (Images 21 & 22). The train then headed south toward Wuhan, (7.6 million residents), the capital of Hubei and a heavy industrial area that is been called the "Chicago" of China. Before reaching Wuhan, there was attractive rolling scenery in northern Hubei (Image 23), then the Yangtze River crossing in Wuhan (Image 24). Just a few miles upriver (the direction of the camera shot), Chairman Mao, at 72 years old, is reputed to have swam across the Yangtze in 1966.

The July greenery of central China was impressive. It continued into northern Hunan province (Image 25) and its capital of Changsha, an urban area of 3.8 million. In Changsha, the train diverted from the Beijing to Guangzhou line and turned eastward toward Nanchang. Along the way, the "peri-urban" development seemed to get more intense (Image 26).

The Nanchang urban area (Image 27) has a population of 2.8 million and sits on the Gan River, which eventually flows into the Yangtze, to the north. It is home of the Pavilion of Prince Teng, on the older east bank city, across from the newer development on the west bank (Image 28).

A few days later, the last leg of the trip from Nanchang to Shanghai Hongqiao took less than four hours. Between Nanchang and Hangzhou, (7.6 million), the capital of Zhejiang, there was more greenery, rolling and mountain country and intense peri-urban development (Images 29-31). Hangzhou has been undergoing a huge construction boom (Image 32). It was less than one hour to Shanghai, and the peri-urban development continued to intensify (Image 33).

All in all, the five train trips had covered more than 3,700 miles (6,000 kilometers) and passed through 14 provincial level jurisdictions.

Trains

The best trains in China are the "G" trains, the "D" trains, and the "C" trains, all of which are of European high-speed rail quality. The "G" trains have a top speed of more than 300 kilometers per hour. The "D" trains have a top speed of 250 kilometers per hour, while the "C" trains are shuttles, such as those operating between Tianjin and Beijing or Changchun and Jilin and tend to operate at 250 kilometers per hour or more.

All of these trains use similar equipment (Image 34). Image 35 is the inside of a 2nd class coach, which have with reclining seats and snack service. All of the trains have information displays in each car indicating train speed, time, etc. (Image 36). Stations may be central as in Tianjin or near-airport distances from the urban core, as in Jilin and Wuhan.

Tickets

Ticket purchase has become simple. Tickets can now be booked from virtually anywhere and paid for by credit card. US residents will pay a service fee of up to $6 per ticket. Confirmation documents are provided over the internet and can be presented at any station in China to receive the tickets all at once. My ticket pickup took no more than 10 minutes at the downtown Shanghai Railway Station.

I would recommend using a travel agency that is located in China, has a toll-free 24 hour number from one’s home country, has agents with good English skills, and a local China number for use when there. I was very happy with travelchinaguide (https://www.travelchinaguide.com/), which meets this description. Train schedules can be accessed at https://www.travelchinaguide.com/china-trains/.

Note: The urban area populations are as estimated in 2016, taken from Demographia World Urban Areas: 12th Annual Edition (2016).

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Changchun, Jilin, China: urban core (by author)

Google

Google

Google from 2009

Google from 2009 Google Street View from 2009

Google Street View from 2009 Google Street View from 2009

Google Street View from 2009 Google Street View form 2009

Google Street View form 2009 Google Street View form 2009

Google Street View form 2009