How will new carpool options like LyftLine and UberPool affect the marketplace of transit services? When mobility conversations turn to Lyft, Uber and other ridesourcing — or ridesharing — companies, the discussion typically centers on their effects on the taxicab business. Here in Chicago, Lyft and Uber recently survived a turbo-charged regulatory battle with cabbies that could have forced them to entirely withdraw from our city.

Ridesharing carpools add a new dimension to the extraordinary rise of these companies. Many users have not until recently begun experimenting with carpooling options, but by all indications their popularity is accelerating. Both LyftLine and UberPool were unveiled in summer of 2014, and then rolled out gradually.

To use LyftLine or UberPool, a rider inputs his or her location and destination on a smartphone, which then displays two options — a traditional rate, and a discounted rate for those who choose to ‘pool’. The driver of a pool may make other pickups and drop-offs. A four-mile trip on UberPool may cost around $6, whereas on UberX (the standard Uber service) it might cost $10; a taxi ride would run much higher.

In communities with lackluster public transit, carpooling fills an enormous void by giving millions without a private vehicle a new, lower cost travel option. Even in areas saturated with public transit, however, this new option promises to reshuffle how people move about.

The opportunity raises critical questions. Will significant numbers of time-sensitive travelers, including commuters, opt to use public transit less, in favor of rideshare service carpools? How much time can they expect to save? To what extent do the additional stops negate the benefits of this option, compared to using transit?

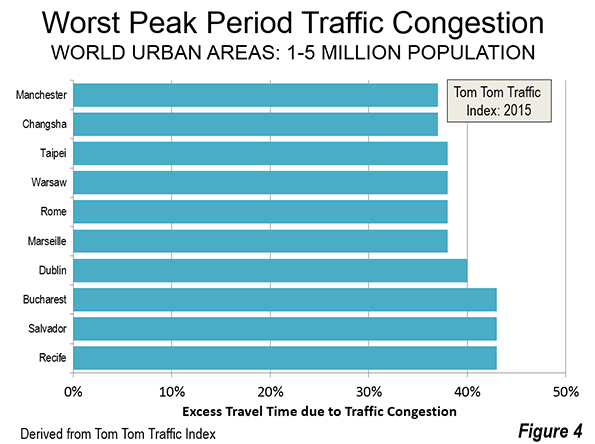

I created a controlled experiment involving 50 one-way trips between various urban locations in a transit-rich part of Chicago. Data collectors measured the differing costs, time, and conveniences associated with UberPool, trains, and buses. One person used Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) services while the other hailed an UberPool (Figure 1).

We evaluated only weekday trips during daytime hours to and from the north and northwest sides of the city, in order to focus on a transit-rich environment. Our trips, which linked the centroids of community areas, averaged about six miles long.

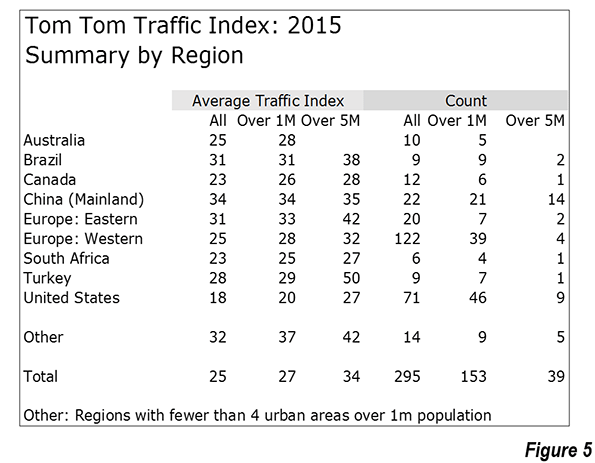

UberPool did not disappoint. Regardless of the type of trip involved, our study found that carpooling tended to get you there faster than public transit, although often not by enough for to justify — for many passengers — the cost difference. The average elapsed time for all UberPool trips was about 36 minutes, besting transit by about 12 minutes. UberPool was faster on 39 trips, while the CTA was faster on 11 (Table 1). The carpooling costs averaged $9.66, compared to transit’s $2.29.

Stops to pick up other passengers were not as prevalent as many might expect, with UberPool trips averaging just under one extra stop. Still, one fifth of all trips made at least two extra stops, while two out of the 50 trips involved three extra stops

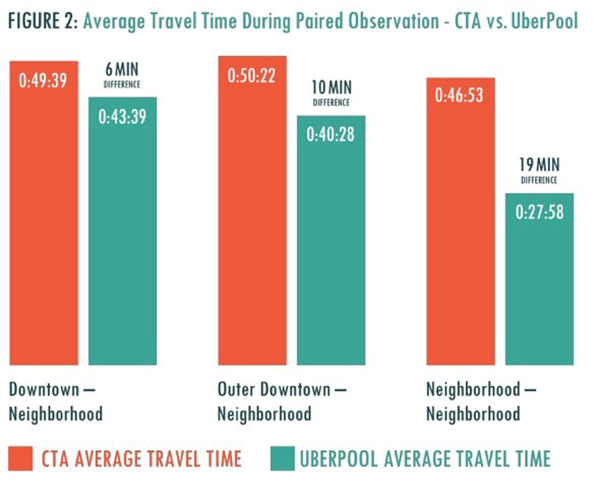

The appeal of carpooling may depend on the type of travel involved. On downtown-oriented trips, the time savings averaged a mere six minutes. UberPool was faster on eleven of these, and the CTA on seven.

Moreover, UberPool can be challenging during rush hour, when it is slowed by traffic congestion and taking rapid transit is often faster due to the heightened schedule frequency.

We suspect that primarily people in a hurry, those carrying heavy or bulky items, or those uncomfortable with transit would be inclined to regularly carpool to work downtown. The level of exertion is also greater on public transit. Our transit passengers were unable to find seats on about one-fifth of trips, and walked more often. UberPool involves minimal walking, whereas the average transit trip involved about a half-mile trek. Eleven transit trips required passengers to hoof it for at least two-thirds of a mile, while three involved doing so for more than a mile.

On trips from the peripheral ‘outer downtown’ to the neighborhoods, though, UberPool outpaced transit by ten minutes. Carpooling starts to look more tempting to the transit rider in this scenario.

The most dramatic benefits from carpooling, however, involve neighborhood-to-neighborhood travel (Figure 2). Such trips can be painful to transit users in Chicago, in part due to our slow pace of getting bus rapid transit off the ground and our ‘legacy’ rail system, with its radial design that focuses primarily on travel to and from downtown. And busses on some routes stop every few blocks.

On these trips, UberPool dominates, averaging 28 minutes per trip, almost 19 minutes faster (about 40 percent) than transit. Carpooling was more than 10 minutes faster on all but four of our 23 trips, and more than an hour faster on one.

A notable negative aspect of using UberPool is, of course, the variability in pricing. Six of the 50 trips involved ‘surge’ pricing (premium fares due to heavy demand), resulting in prices as much as 60 percent above the normal fare. We did not study the price and speed of UberPool during the evening and late-night hours, when demand is reportedly heaviest, and when surge pricing appears to be more prevalent.

The inescapable conclusion is that carpooling services are appealing to far more than transit-averse and extremely time-conscious travelers, although perhaps not as an option that many commuters would use daily. UberPool tends to perform best precisely where transit is at its worst, e.g., on trips between the neighborhoods, especially during the off-peak periods when traffic is lighter.

On one level, our results support the conclusions of a new Shared Use Mobility Center/American Public Transit Association report showing that such mobility innovations tend to be complementary to public transit. Shared-use services like Lyft and Uber fill the gaps that exist in urban bus and rail operations, and encourage people to pursue lifestyles that do not center on private cars.

Still, carpooling should also be regarded as a potential game-changer. Federal guidelines recommend that analysts assume the average urban traveler values time savings at $24 per hour. An average traveler on an UberPool making a neighborhood-to-neighborhood trip may, therefore, by arriving about 20 minute earlier than a transit rider, derive a benefit from carpooling of around $8 per trip, which would be a far greater amount than the extra cost. The most time-sensitive travelers and groups of travellers would derive an even higher benefit.

Even though rideshare carpools represent a mobility breakthrough, it unfortunately continues to take a backseat in the taxi-centric debate over Lyft and Uber. It is certainly going to pose an increasing challenge to public transit agencies. Heightened competition in urban transit markets appears here to stay, and is now poised to bring dramatic changes to the way we travel.

Joseph P. Schwieterman is director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development and Professor of Public Service at DePaul University in Chicago.

Flickr photo of the S2 smartwatch from Samsung Newsroom: Travel NYC with the Gear S2 and Uber