Perhaps for the first time in nearly seven decades a serious debate on housing affordability appears to be developing in the United Kingdom. There is no more appropriate location for such an exchange, given that it was the urban containment policies of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 that helped drive Britain’s prices through the roof. Further, massive damage has been done in countries where these polices were adopted, such as in Australia and New Zealand (now scurrying to reverse things) as well as metropolitan areas from Vancouver to San Francisco, Dublin, and Seoul.

A healthy competition has developed between the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition and the Labour Party to finally address the problem of the resulting land and housing shortage that has driven prices up so much relative to incomes.

It probably helps that public opinion seems to be changing. A recent MORI poll found that 57 percent of respondents considered rising house prices to be a bad thing for Britain, compared to only 20 percent who though it a good thing.

It has been more than a decade since Kate Barker, then a member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England (the central bank) was commissioned by the Blair Labor government to examine the issues. Her conclusions were clear. Britain has a serious housing affordability problem and its restrictive land use policies were the cause. These higher housing costs, the largest element or household expenditure have reduced the standard of living and increased poverty beyond what would have occurred if urban containment regulation had not destabilized house prices. The Economist notes that home ownership is falling and that the number of couples with children who are renting has tripled since the late 1990s.

Planning and Chickens

This week, The Economist weighed into the debate (Britain’s planning laws: An Englishman’s home):

"Now that the economy is at last growing again, the burning issue in Britain is the cost of living. Prices have outstripped wages for the past six years. Politicians have duly harried energy companies to cut their bills, and flirted with raising the minimum wage. But the thing that is really out of control is the cost of housing. In the past year wages have risen by 1%; property prices are up by 8.4%. This is merely the latest in a long surge. If since 1971 the price of groceries had risen as steeply as the cost of housing, a chicken would cost £51 ($83)."

For those of us unfamiliar with the cost of chicken in British hypermarkets, The Daily Mail says it is about £2 ($3). Indeed, even the chicken industry suffers, as planning restrictions are getting in the way of adding the chicken farms Britain requires.

Moreover, the high costs cited by The Economist are after the house prices increases that had already occurred by 1970. Even then, before such inflationary pressures were seen elsewhere, Sir Peter Hall characterized soaring land and house prices as the biggest failure of the 1947 Act. Hall had led a major research effort on the subject, which produced a two-volume work, The Containment of Urban England (See The Costs of Smart Growth Revisited: A 40 Year Perspective).

From Affordable to Unaffordable

While the historic relationship between household incomes and house prices (the "median multiple") was under 3.0 across the United Kingdom as late as the 1990s, it has now deteriorated to more than 7.0 inside the London Greenbelt. Unbelievably it has risen to elevated levels even in the less prosperous the north of England. For example, depressed Liverpool has a median multiple over 5.0, which is 60 percent above the maximum historic range and making the metropolitan area "severely unaffordable." Liverpool is probably best compared to Cleveland in the United States for its economic distress.

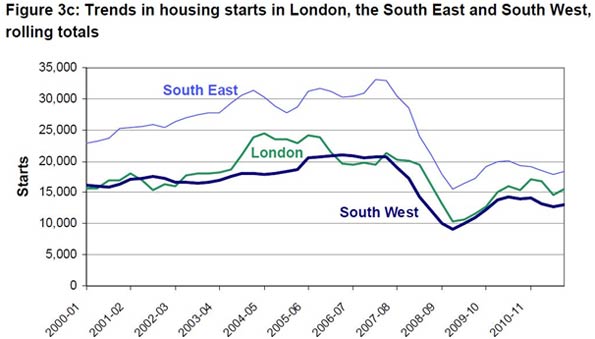

The shortage of housing in Britain has become acute. There are additional concerns that the globalization of housing markets has hit London particularly hard and is driving households out of the housing market.

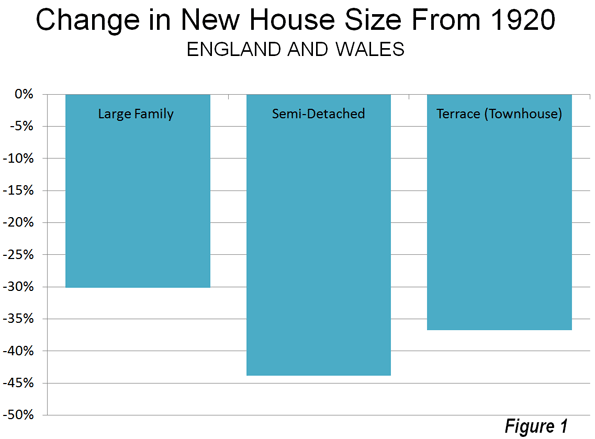

More Money, Less House

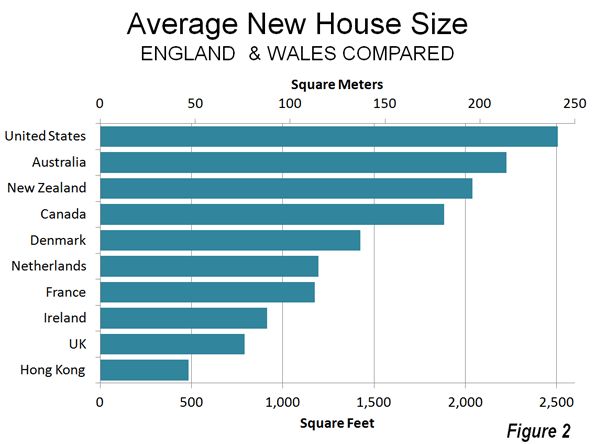

Through all of this, Briton’s are getting less for their money. Since 1920, the average size of a new large family house has been reduced 30 percent. Semi-detached houses are 44 percent smaller and townhouses (terrace housing) is 37 percent smaller (Figure 1). Britain now has some of the smallest new housing in the world. The average new house in continental Europe is 50% or more larger than in England and Wales. New houses are two to three times as large in Canada, New Zealand, Australia and the United States (Note 1). In some US cities, residents can build "granny flats" which are larger than new houses in Britain. For example, San Diego’s limit for granny flats of 850 square feet exceeds Britain’s average new house size of 818 square feet.

Paving Over Ohio?

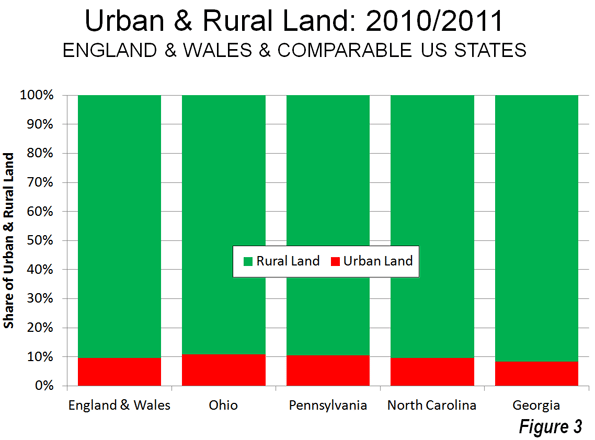

Of course, those who see urban expansion (the theological term is "sprawl") as ultimate evil imagine an England and Wales being literally paved over by allowing people to live as they prefer. They need not worry.

For example, England and Wales is less crowded than spacious Ohio, with its rolling hills and extensive farmland. According to the 2011 census, only 9.6% of the land in England and Wales is urban, the other 90.4% is rural. In Ohio, on the other hand, 10.8% of the land is urban and only 89.2% of the land is rural. Even the state of Georgia, with the least dense large urban area in the world, Atlanta, has roughly as much rural land (91.7 percent) as England and Wales (Figure 3).

Every Gram is Sacred?

Originally, urban containment was justified on social and aesthetic grounds. However, curbing greenhouse gases is now used as the raison d’etre for highly restrictive housing policies. Urban policy in England and Wales and elsewhere has been hijacked by a philosophy that any gram of greenhouse gas that can be reduced must be, regardless of its impact on society, the economy, the standard of living or poverty.

One of the worst conceivable strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions is to waste money on costly and ineffective measures. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has indicated that sufficient reductions in greenhouse gas emissions can be achieved for a range of from $20 to $50 per ton. Urban containment policy cannot deliver for this price. In contrast, improving automobile fuel efficiency is forecast improve greenhouse gas emissions, even as driving continues to rise with a growing population (see Urban Planning for People). In addition, the higher house prices associated with urban containment policy are well beyond the IPCC range.

No program can produce substantial greenhouse gas emission reductions that does not focus on higher value strategies. Urban containment has no high value strategies.

Planning, People and Poverty

Britain’s land policy competition between the political parties is long overdue. Coalition Communities Secretary Eric Pickles, decries "the way families are trapped in ‘rabbit hutch homes’." The Labour Party opposition has promised that, if elected in 2015, steps will be taken to increase land supply and housing affordability, so that "working people and their children" have the "decent homes they deserve."

The Economist states the issue squarely:

"Building on fields in a country that is as crowded as England will always rile some people, however well-designed the system. But the alternative is worse: a nation of renters and rentiers, where only the rich own houses."

—————–

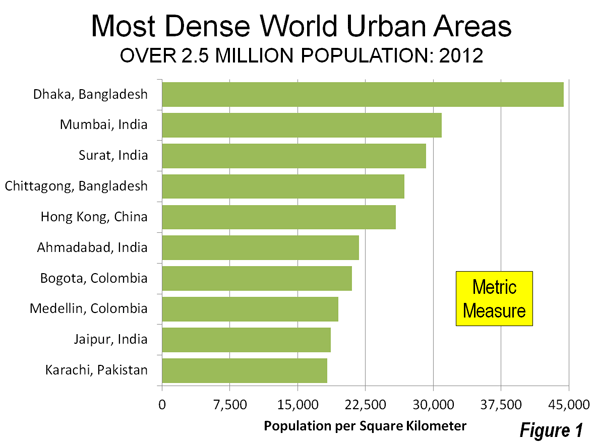

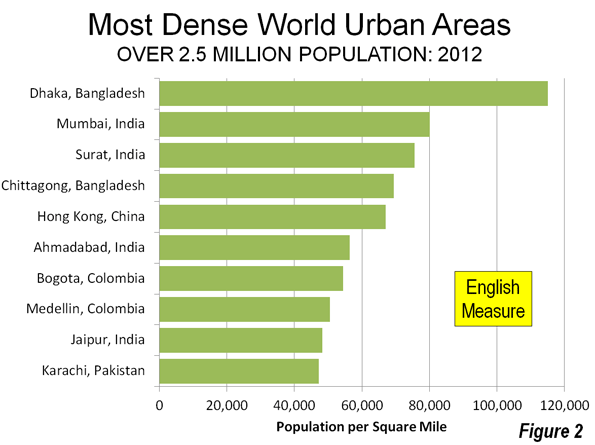

Note 1: As Figure 2 indicates, Hong Kong housing is considerably smaller than that of England and Wales. Hong Kong really is the ultimate smart growth or urban containment city. It has the highest urban population density in the high income world. It has the highest share of its commuters using mass transit to get to work. Its traffic congestion is intense. And, predictably, it has the highest house prices relative to incomes yet documented in the high income world.

We need to be spared the "sun rises in the west" economic studies claiming that somehow the laws of economics, that work so relentlessly to drive up prices where supplies are constrained in other industries (such as petroleum, corn, etc.) have no effect on land and housing.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

Photo: St. Pancras Station (London), by author